Greece’s Corinth Canal, arguably the world’s most iconic waterway, becomes 128 years old this summer — and it is ageing badly.

Repeated landslides on its steep earth walls have led authorities to suspend operations on and off since November last year.

At the end of January, operating company Corinth Canal Co realised that even more drastic measures were needed to ensure safety: traffic was interrupted until further notice and the waterway was placed in a state of emergency.

That was less to prevent any risk of a wholesale collapse but rather to cut through red tape and speed up the tendering of surveys for repairs. Local players worry the waterway might take weeks to reopen, perhaps even months.

“I don't remember the canal shutting down for such a long time in the past, ever," Costas Tselikas, head of Elefsis Shipping Agency, said.

The closure is not a blow to big oceangoing shipping. Although it was a major feat of engineering when it began operating in 1893, the Corinth Canal is too narrow and too shallow for large, modern ships. Vessels wider than 24 metres (79 feet) cannot travel along it and it is just 8 metres deep.

However, it remains important for domestic trades and tourism. More than 5,000 ships and boats sail through it each year — just to enjoy the view or to benefit from the hugely reduced travel times between the Aegean and the Ionian seas.

Vessels en route from Piraeus to Patras — two of Greece's biggest ports — save 18 hours and about a third of their fuel by taking the canal. A small cruiseship traveling from Venice to Piraeus cuts its voyage by almost one-fifth to 721 miles.

In October 2019, the Fred Olsen Cruise Lines-managed, 24,300-gt Braemar (built 1993) became the longest vessel to travel through the 6.3 km (four mile) long, arrow-straight gorge that links the Gulf of Corinth to the Saronic Gulf on a west-to-east axis.

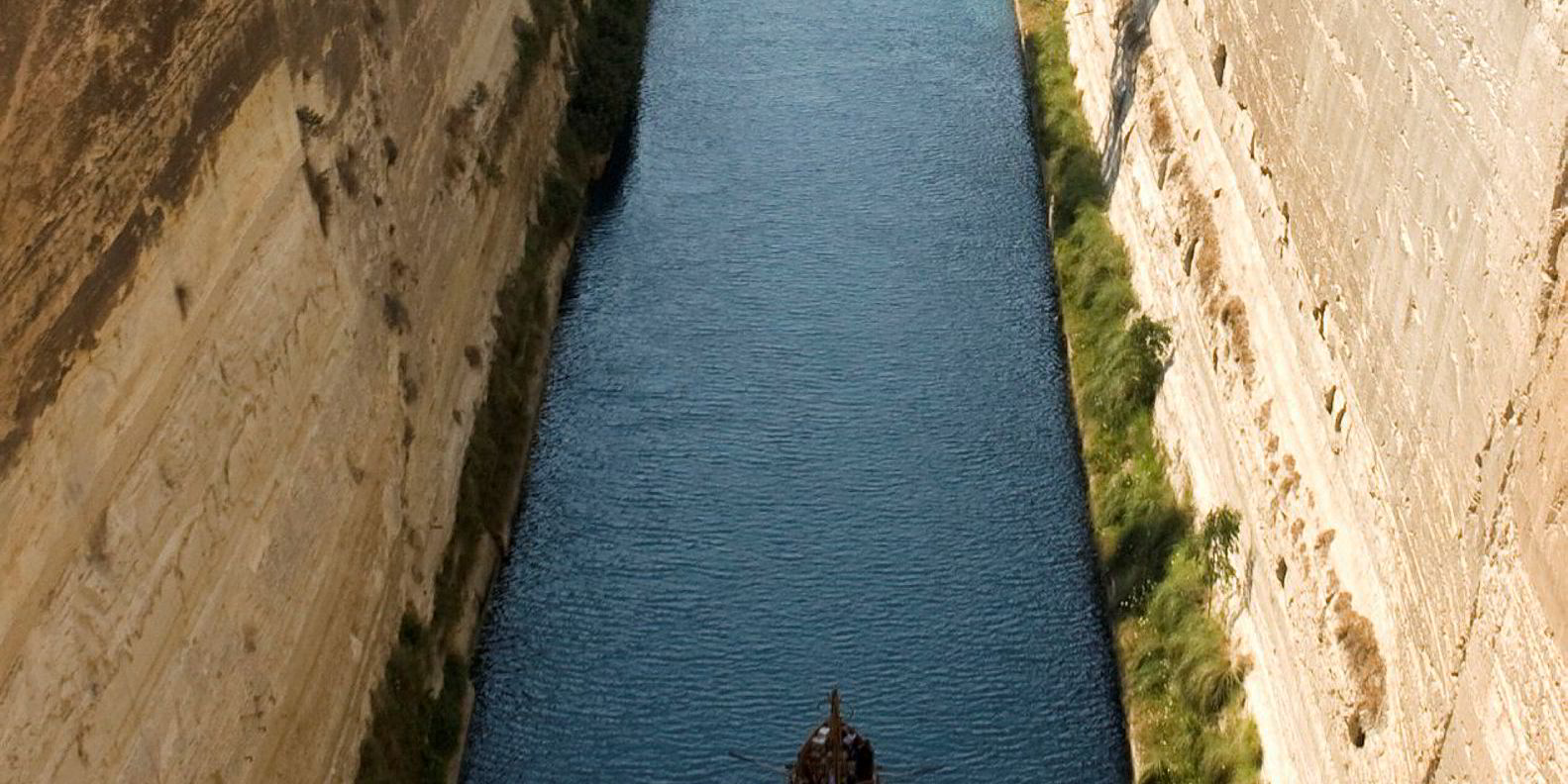

Footage of that impressive — if, at times, claustrophobic — crossing arranged by Elefsis Ship Agency can still be seen on YouTube (above).It shows the ship squeezing through canal walls rising up to 80 metres above sea level at a near-vertical angle of 80 degrees.

That passage may have been a treat for tourists on board the Braemar in 2019 but it became a scary experience for the 17 seamen on the 6,400-dwt cement carrier Seaven Star (built 2007) last November.

The vessel was towed through the canal on the night of 22 November when about 1,200 cubic metres of earth came crashing down ahead of its bow (below).

Fragile beast

A stone pediment supports the canal from its bottom up to about two metres above sea level. However, the slopes above it are in the natural state of rock and soft earth in the geologically unstable land strip that connects mainland Greece with the Peloponnese.

That makes the canal a fragile beast. Slides occur frequently, often from natural erosion but also after heavy rains and earthquakes. During World War II, German occupation forces destabilised the walls further, blowing up bridges and throwing down trains to block the waterway during their retreat.

To restore traffic on the waterway, authorities plan €9m ($10.9m) of construction works and a new online system to monitor the slopes and provide early landslides warning. Furthermore, a new urban plan is under consideration to revive the entire canal region and bring in more tourism.

Substantial sums will be needed.

Dimitris Dimitriadis, a former non-executive director of the Corinth Canal Co between 2011 and 2014, said: “To restore the aged and historic canal’s full length can take hundreds of millions of euros.”

Sums like that will not be easy to muster in cash-strapped Greece. Covid-19 has not made things any easier. As tourism sailings collapsed, Corinth Canal Co’s revenue plunged as well.

Technical problems and shortness of funds are nothing new in the canal’s history. They go as far back as Periander, tyrant of Corinth who was the first to conceive, and eventually drop, a plan to build the canal in late 7th century BC.

A few centuries later, Roman emperor Nero personally swung a golden pickaxe to launch construction works. The Venetians tried their hand in 1687. All failed.

If the Greek gods wanted the Peloponnese to be an island, they would have made it so themselves, a Greek oracle warned Periander.