The use of offshore flags and ownership locations is so much part of the shipping industry that reference to the practice is a total non-story to most maritime executives.

It would almost be like questioning the need for a main engine or propeller to ask whether it is really necessary to use Panama, Malta or Liberia when your shipping company has an operational head office in Oslo, Athens or London.

Indeed, this method of going about business got underway almost a century ago when US companies started to flag out to Panama.

So it is not surprising that the use of offshore locations is taken for granted mainly — although not, seemingly, by the latest maritime superpower, China.

State-owned players worldwide may have their failings but their commitment to the home base is usually solid.

The whole issue of foreign registers has only really mattered in the past to national trade unions. They have been angry where they deemed “flags of convenience” (FoC) were used to bring in cheap foreign crews.

The International Transport Workers' Federation (ITF) has been waging its “FoC campaign” against this practice for decades.

But apart from national seafaring unions and the ITF, none of which have a great deal of political clout, few in the wider world have been much bothered what the maritime sector did: until today.

Now you have a situation where the release of confidential documents, dubbed the Paradise Papers, has caused a political storm — in the West anyway.

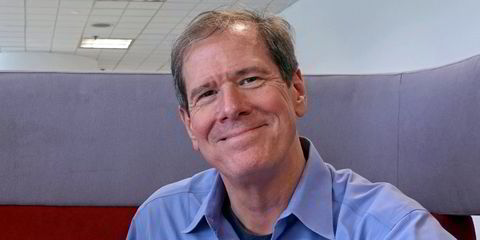

Turkish Prime Minister Binali Yildirim has walked into a minefield and is facing demands to resign over his family’s alleged links to offshore shipping companies

The headlines have largely been caused by Queen Elizabeth II, who was found to be holding some investments offshore; or Wilbur Ross, the US commerce secretary, having offshore connections that lead eventually to some controversial Russian investors, as my colleague Julian Bray reviewed last week.

None of this is illegal but it is certainly politically incendiary. Why?

Because many hard-up people around the globe are still paying for the 2008 financial crisis through higher taxes or lower benefits.

Politicians and pop stars

The Paradise Papers, and the Panama Papers before them, show wealthy businessmen, politicians and even pop stars, such as Bono, have been avoiding the run of the mill taxes that most of us take as normal to run public services, by using offshore havens to squirrel their cash away.

This kind of action undermines the arguments for globalisation, if not liberal democracy itself, and is no doubt one factor why you get popular rebellions such as Brexit and Donald Trump.

The problem for shipping is caused by the fact that a significant part of the industry has come to rely on offshore flags or domiciles. How do you compete if you do not? There are obviously some variations in this, not least the difference between high-quality offshore registers and lower class ones.

The system may be acceptable until the maritime sector wants something from the political world of Brussels or London or whoever, such as understanding over the difficulties of reducing its carbon emissions.

Public sympathy, or the social licence to operate, risks being badly undermined by revelations that offshore registers are used extensively in shipping.

Finnish Seamen's Union president Simo Zitting told his local paper it was often nigh impossible to work out who really owned a particular vessel.

Indeed, I remember my first day as a shipping reporter 25 years ago being told never to write who “owned” a vessel, just “controlled” it. That was particularly true of casualties where any reference to apparent ownership tended to be met with a flood of denials.

Zitting argues: “The chain of ownership can be in several tax havens. There can be double or triple versions of bookkeeping documents and different versions of documents.”

So it is not surprising the Turkish prime minister, Binali Yildirim, has walked into a minefield and is facing demands to resign over his family’s alleged links to offshore shipping companies.

His accusers claim the moves may not be illegal but are immoral. Those accusers are political opponents it should be said, but still the charge looks damaging in the court of public opinion.

Shipping does not have to rely on offshore flags and states but 100 years on it is not easy to see how this addiction can be broken.

Anyone brave enough to organise a conference on the subject?