It has not yet reached buzzword status and certainly has its lovers and loathers, but ammonia is not far off making its debut as a marine fuel.

In 2026, a newbuilding fitted with an ammonia dual-fuel engine is due to emerge from a Japanese shipyard, and shortly afterwards the first ammonia-fuelled, midsize gas carriers are scheduled to be handed over in South Korea.

But these are very early days and the first pilot projects albeit for a near zero-emission fuel which, in its green form, could constitute a major part of the marine market.

Sifting out the newbuildings with a firm commitment to install or retrofit a dual-fuel ammonia engine from those simply claiming a readiness for the fuel when the propulsion systems are commercially available is not simple, particularly with the level of secrecy around projects.

Clarksons Research currently lists just 15 ammonia dual-fuel capable vessels on its database. Of these 13 are newbuildings, mostly capesize bulkers and midsize gas carriers. Two — a tug and a platform supply vessel — are lining up as retrofits.

But flip that to “ammonia ready” status and the brokerage research arm records 348 vessels comprising 249 on-order ships and 99 existing ships, some of which are billed as capable of using other alternative fuels.

Bunker brokers described ammonia as “high on the list of a lot of people’s agendas” and spoke about large numbers of letters of intent in connection with ammonia-fuelled tonnage.

One said that, behind the scenes, a great deal is happening but nobody is prepared to say too much.

Some want to be first to market with the zero-emission fuel and are closely guarding their moves, the broker explained. Others are concerned that ammonia as a marine fuel has some serious opponents — largely due to its toxicity — and do not want to advertise their engagement where confidence ratings for the fuel can be negative.

LansdowneMoritz managing consultant Gary Regan likened today’s situation on ammonia fuelling to that of electric cars. He said that while there may be many Teslas on the road, that side of the technology is running ahead of the supply — citing the image of an electric London cab being recharged from a diesel-fired generator.

Regan is philosophical about such set-ups, commenting that they are “heading in the right direction” by effectively creating demand.

For ammonia and marine, he said the positive is that the engine technology appears to be nearly there.

Green demand

But the big challenge is on the supply side over where the volumes will come from and how they will be supplied to ships.

To ensure ammonia supply, someone will have to commit to at least a 10-year contract to underwrite production projects on a take-or-pay basis, Regan said.

“Shipping isn't particularly well placed to do that,” he added, explaining that the demand from one or two vessels is very small relative to the size of the production facilities and that shipowners are generally averse to 10-year procurement contracts, particularly when they cannot always guarantee that they will be bunkering in the same place.

Regan said ammonia producers are not taking final investment decisions on projects as they cannot yet nail down long-term offtakers.

He said it will likely take buyers such as the fertiliser or power sectors to start buying at scale, which could then unlock some supply for shipping to trade around.

So vessels that, in theory, can trade on green ammonia may emerge in advance of supply — like the electric car picture.

LansdowneMoritz estimates about six million tonnes per annum of blue and green ammonia production is planned or under construction. This comprises around 2 mtpa of blue ammonia in the US, another 1.2 mtpa of the green version of the product from Saudi Arabia’s huge Neom project and a mix of blue and green production in the United Arab Emirates.

The consultant describes these volumes as “a drop in the ocean” compared with the International Energy Agency’s demand estimates of 50 mtpa by 2030 and 250 mtpa by 2040.

Engine designer MAN Energy Solutions chief executive Uwe Lauber said in March that it would take time to build up the supply of green ammonia and said this is unlikely to scale up before 2030.

Regan admitted to fielding questions from ammonia producers asking if the shipping market would be a customer for their projects. The consultancy answers yes, but with the rider that it is unlikely to prove an anchor customer.

“I think there's going to be a big role for intermediaries,” he said, citing companies such as Yara International or Trafigura, which can accept the risk of long-term supply contracts and aggregate volumes for customers.

But at present green or blue ammonia is unlikely to be produced at scale in Europe, so a network of ammonia bunkering terminals will be needed for shipping.

Supply chain build-out

Another issue will be infrastructure.

Clarksons Research database shows 26 ports globally with proposed ammonia bunkering facilities.

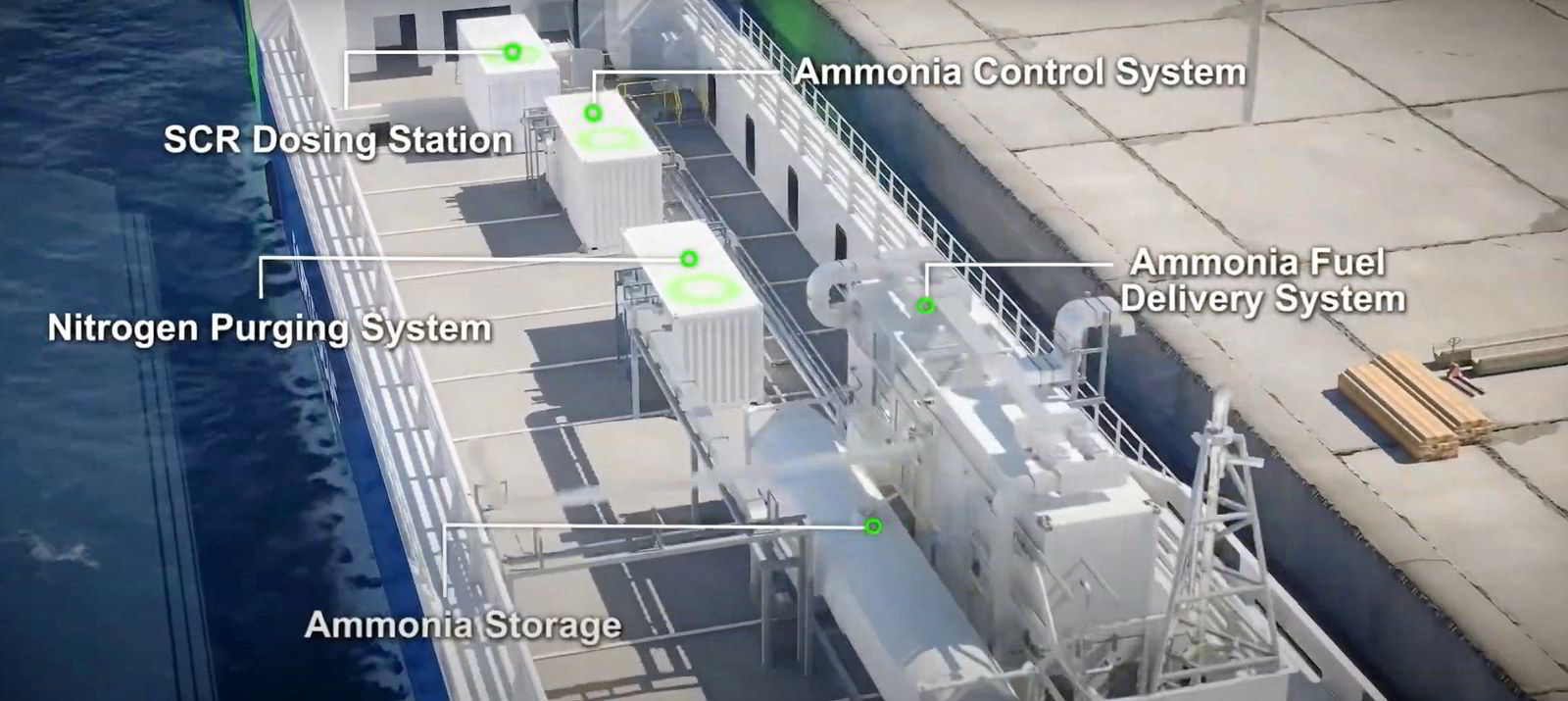

At the end of March, Yara International said it had won approval from the Norwegian authorities to install a 1,000-cbm floating stationary barge at Fjord Base in Floro that is primarily expected to be used to bunker offshore vessels with ammonia.

But Regan pointed out that the large ammonia production projects will not necessarily be in the right place for bunkering.

“Putting together the whole supply chain for ammonia is going to be very difficult,” Regan added.

He said ship-to-ship transfer of ammonia will take years to develop, largely due to the fuel’s toxicity.

The Society for Gas as a Marine Fuel, or SGMF, is about to produce a full lifecycle analysis for ammonia based on first-hand data.

SGMF general manager Mark Bell admits this will largely focus on well-to-tank information but added there is a little tank-to-wake data included and it is “positive”.

It is also planning to produce its first bunkering guidelines for ammonia by the end of this year. Fundamental to these will be the need to keep it in a liquid state as once it vapourises it becomes a toxic gas.

Bell said: “Put simply, ammonia will need to be ‘clean or nothing’ — so either blue or green ammonia.” He described green or fully “clean” ammonia as “the end game fuel” and “a real goal to go for”.

But he cautioned that it would need to be shifted to the right place for bunkering. “Don’t underestimate the emissions cost of moving the fuel,” he said.

He urged the industry not to forget the lesson it learned from LNG, which was available everywhere, but nowhere as a fuel for shipping and needed the build-out of its own bunkering network.

Regan highlighted that it took LNG bunkering around 10 years to develop and, while ammonia may have added impetus from decarbonisation, this is balanced by the fact that the upstream element of the supply chain does not exist, and it is a more hazardous fuel.

“If it goes at the same pace as LNG, even with those tailwinds behind it, I still think it will be doing quite well,” he said, adding that this is a realistic view of the challenges of developing the whole supply chain.