Enough bio-LNG could be produced to supply 16% of marine fuel demand by 2030, a new study produced by industry coalition SEA-LNG has found.

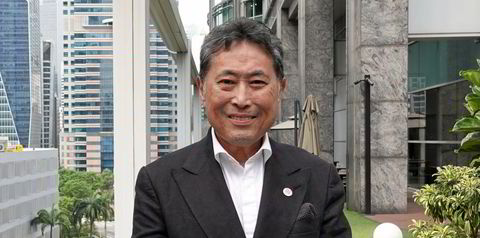

The work, done in partnership with Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University’s Maritime Energy and Sustainable Development Centre of Excellence (MESD), and presented on Wednesday, showed that this would be done by blending it at a 20% rate with fossil LNG.

The study also showed that bio-LNG can cut greenhouse gas emissions by between 50% and 80% compared to using marine diesel. But plant and onboard methane emissions need to be minimised to achieve this.

Presenting the findings MESD research consultant Bruno Piga said the advantages of bio-methane — which can be liquefied to form bio-LNG — is considered as one of the most important renewable fuels for decarbonisation.

He said the average cost for delivered bio-LNG for shipping today is around $30 per gigajoules (GJ) with some big variations. But this is forecast to decline by about 30% to $20 per GJ by 2050 as production scales up.

Bio-methane is not cheap, he said, but will decline and while bio-LNG will be more expensive than fossil LNG it can be cost-competitive with other biofuels.

“It is forecast that the production of bio-methane will explode in the next 10 to 15 years,” he said, adding that it will compete with hydrogen in the future.

Piga flagged up the advantage of bio-LNG are that engine technology for LNG is already mature, existing bunkering infrastructure exists and it can be blended with fossil fuels to meet emissions targets.

The challenges are whether there will be enough biomass to support the production of the fuel for shipping and the costs of the logistics for supply.

Piga said that while not all sustainable biomass can be utilised for bio-LNG production, a “significant portion” can be used for shipping.

But he stressed there is a limited amount of biomethane and several competing sectors for it.

Piga said material users, such as those for the wood and paper industries will likely be first to the table for it, swiftly followed by the hard-to-abate aviation sector.

He logged shipping as a “medium priority”.

Speaking further about bio-LNG emissions he said using manure as feedstock for bio-LNG can give negative emissions.

Even very low blendings of bio-LNG with the fossil version of the fuel can produce “super reductions” in emissions, Piga said.

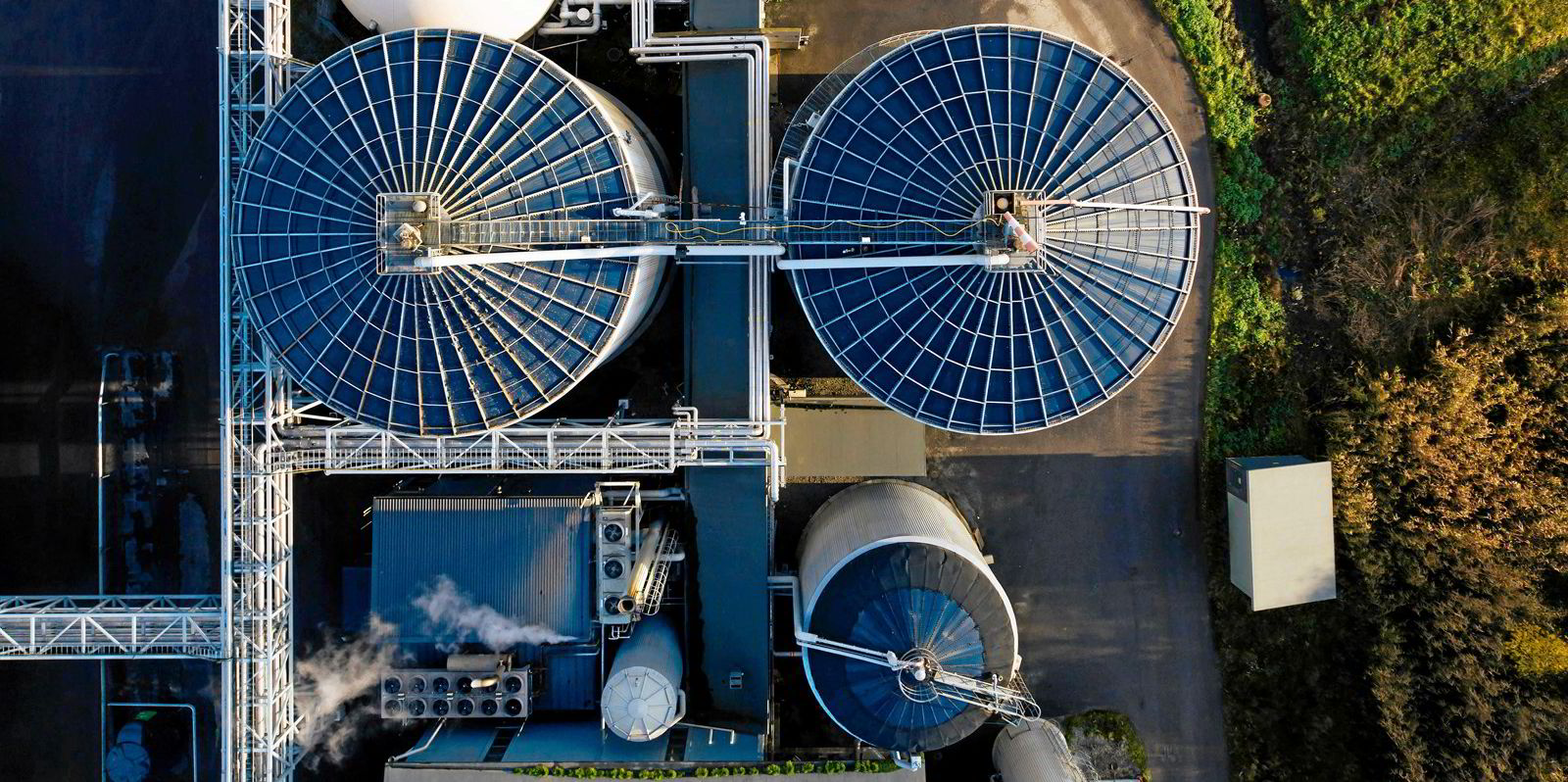

On the supply chain for bio-LNG, he said production of bio-methane is by nature decentralised with small scattered low-scale plants.

He said one of the interesting and cheaper options to bring it to the market for shipping is to use existing infrastructure and inject bio-methane into the gas grid and transfer it to a central liquefaction hub and from there to the bunkering station.

Even more efficient is the use of green gas certificates of origin which allows users to buy the bio-LNG from the terminal.

But he stressed that this needs industry awareness and a regulatory framework.

Piga said bio-gas and bio-methanes are starting to be recognised as very important for the future of decarbonisation.

“Something is moving,” he said. “We believe that in the next few years we will have a very strong explosion of bio-methane.

“The shipping sector needs to be focused on it if it wants to get bio-LNG.”