Russia has inked ambitious plans to open up the Northern Sea Route (NSR) for year-round navigation from 2025 — but with fossil fuels underpinning exports from the region, questions are being asked about the sustainability of its plans.

The official document, The Northern Sea Route Infrastructure Development Plan 2035, was signed off by the then prime minister Dmitry Medvedev in the dying hours of 2019.

The plan’s 84 development strategies cover a huge range of initiatives, which largely fall to state nuclear authority Rosatom to oversee.

Reconstruction and dredging

These include the reconstruction and dredging of Arctic ports, new railway lines and upgrading of existing airports to serve the surrounding oil, gas and mineral-producing regions.

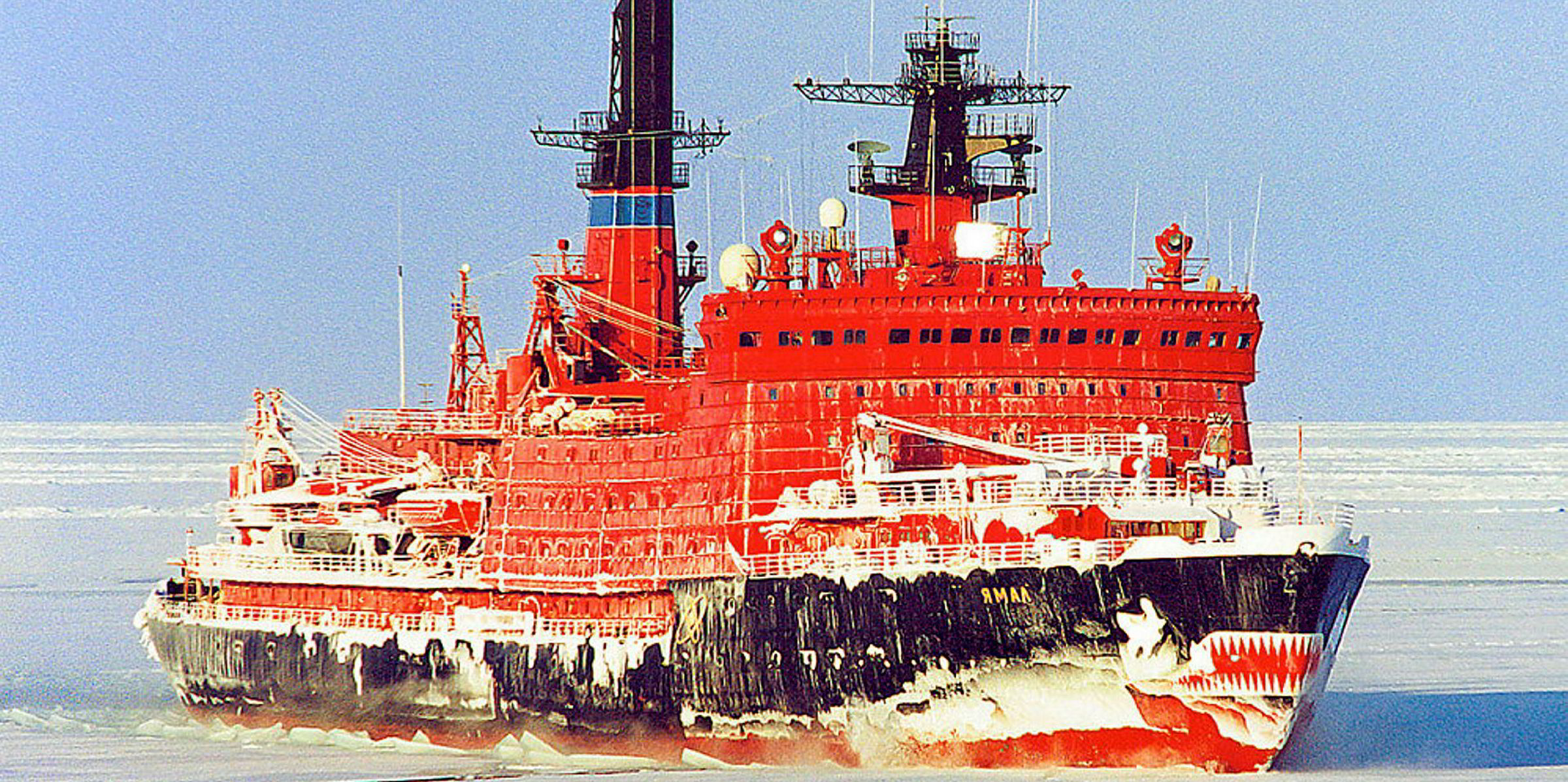

The plan also covers the development of a larger fleet of icebreakers to serve the NSR, search-and-rescue services for the region, and the creation of key transport hubs.

Work has already started on the creation of what would be a huge hub at Murmansk, at the western end of the NSR.

Two large dry docks have been built at Kola Shipyard and the first concrete has been poured for the initial huge gravity-based structure that will house the liquefaction units for the Novatek-led Arctic LNG 2 project.

At a conference in the northern Norwegian city of Kirkenes this month, the Murmansk authorities presented what one delegate described as “quite ambitious” plans to develop an LNG terminal, which would handle transshipment operations.

At the opposite eastern end of the NSR, plans have been outlined to develop a similar base at Kamchatka.

Slots have been reserved at South Korean shipbuilder DSME to build two giant, 360,000-cbm floating storage units for LNG cargoes being shipped east from Novatek’s Arctic projects.

Those working closely with this business said contracts on these were due to be inked early this year. But they have been delayed while Novatek concentrates on the LNG carrier newbuilding business for its Arctic LNG projects.

Central to the year-round navigation on the NSR is the provision of more icebreakers to escort vessels making the transit.

Russia already has a trio of new generation nuclear-powered icebreakers under construction, with more planned.

But the first under-construction LK60Y vessel — the Arktika — is already running two years late and has been delayed further due to an electrical fault. This has led some Russian observers to speculate that this may delay the opening of the NSR.

Kjell Stokvik, who is managing director for the Centre of High North Logistics, which follows developments in the Arctic region, said ice conditions in Russia are difficult to predict, so making icebreakers an important element of the NSR plans.

Stokvik and other delegates attending the recent Kirkenes conference spoke about the politicised nature of discussions between the different country representatives, with the US, China and Norway all upping their interest in the region.

Cosco efforts

Cosco, in particular, is ploughing cash into additional shipments along the NSR.

But Russia is also encountering a backlash to Arctic shipping.

Canada has become the latest to back a phased ban on the use of heavy fuel oil by ships in the Arctic, leaving Russia isolated as the only one of the eight Arctic states opposing the proposal — while the Clean Arctic Alliance, a coalition of 18 non-governmental organisations, wants tougher restrictions.

Companies such as Nike, Gap, Hapag-Lloyd and Evergreen Marine Corp have signed the Arctic Corporate Shipping Pledge, to avoid shipping goods through the region.

This month, there were the first signs that Russia could be responding to the climatic concerns.

The country’s Natural Resources Ministry has said a special commission, which will include representatives from the ministry, will look at proposals to ban ship-to-ship oil transfers in Arctic waters.

Stokvik pointed out that Russia will take over as head of the Arctic Council next year and may use its position to garner more international support for the country’s plans to develop the region.

“We see a shift in Russia now to look at the whole package,” he said.