The first sole female winner of the Onassis prize for shipping was honoured last night in London for decades of research from early computer modelling of maritime markets to the potential impact of autonomous vessels. And it all started with a 1970s Datsun Sunny.

Since publishing her postgraduate thesis in the 1970s on the business cycles of the tanker sector, Professor Siri Pettersen Strandenes has been a prolific researcher and educator whose work has cast light on current debates including the impact of environmental regulations on the industry.

Her desire to study shipping and international trade was driven by curiosity about the economic and global forces shaping her native Norway before and after the arrival of oil wealth in the 1970s.

As a child in the 1960s, fishing and shipping were the main export industries.

Then came the arrival of grapefruit and kiwi fruit in Norwegian shops and a wave of small, cheap Japanese cars that challenged the German and Scandinavian dominance of the local motor market.

In 1970, the Datsun Sunny became the first Japanese car to appear in the top-10 best-selling cars in Norway, according to Best Selling Cars Blog.

“I started driving lessons and I was looking for a car,” she told a ceremony in central London. “Norway didn’t produce any cars ... but I observed a small car, a Datsun.

Hooked on shipping

“How could a Japanese car compete with a Swedish car that could just drive across the border? The answer was shipping, efficient transportation, and I was hooked.”

The Norwegian economist becomes only the second female winner of the prize, which was established in 1978 based on a request in the will of shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis.

She is the first to win it on her own. The first female winner, Professor Mary Brooks of Dalhousie University, shared the prize with a male academic in 2018.

Other awards were given to Professor Darrell Duffie of Stanford University for his work on finance and Professor Marc Melitz of Harvard University was honoured with the international trade prize.

The prizes, with $200,000 grants for the winners, are jointly awarded every three years by the Onassis Foundation, London’s Bayes Business School and its Costas Grammenos Centre for Shipping, Trade & Finance.

The prizes were the first since 2018, owing to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Strandenes has been recognised for a formidable body of work that continued to be published after she retired, aged 70, in 2019.

On being announced the winner last month, Strandenes said she hoped the award could “inspire the next generation of smart, talented young women to strive for excellence in their respective fields”.

She told TradeWinds that “almost everyone was a man” when she first embarked on an academic career.

She was just one of 16 women among more than 200 men on her degree course at the Norwegian School of Economics (NHH) and later became the university’s first female professor.

“For me, that wasn’t a very big problem, but when I started to get female students, they were especially interested in how I was handling this situation,” she said.

“But in the beginning, that wasn’t my motivation. My motivation was that I was interested in international trade and shipping.”

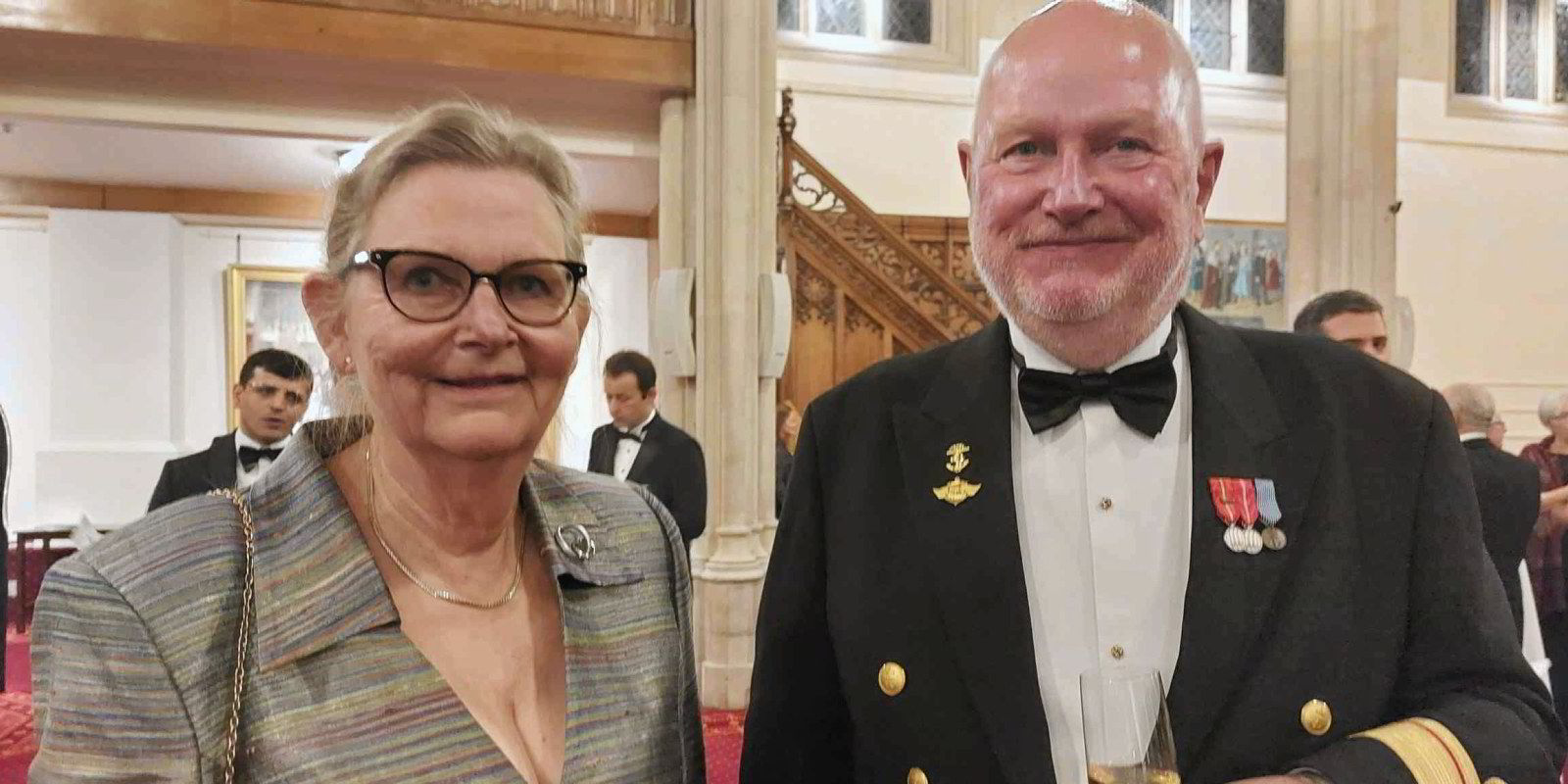

She said she was also inspired by letters from her brother, Jan, a naval officer and later Surgeon General of the Norwegian Armed Forces, about life on the sea. He was at the event in London on Tuesday to see her receive the award.

Her papers and academic research explore issues that have become increasingly significant to shipping.

She developed a computer model in the 1980s that demonstrated the interplay between oil shocks, time charter rates, spot markets, secondhand values, scrapping levels and newbuildings.

It allowed her students at NHH to discover and understand the linkages between different areas of the market.

“Of course, to make a similar model today, you can use an Excel sheet, and people do,” she said.

In 2017, she published a paper with one of her former students — Roar Adland, now global head of research at SSY— about the impact of emission control zones on vessel speed using data from 7,000 ships.

The answer was not much.

“Our thinking on this was that being on time in port was more important ... and the price differences were not big enough,” she said.

She added that the findings are of relevance as shipping joins the European Union’s Emissions Trading System from 2024, which is aimed at rewarding the use of cleaner fuels, efficiency and slow steaming.

“So, as an economist, I still believe in pricing,” she said.

Her later papers included an examination of autonomous vessels and the economic impact of smaller crews but larger land-based technical operations.

She believes it will be one of the key areas, along with reduced emissions and the impact of geopolitics and economic growth on shipping patterns, that will keep her students busy in the coming years.

The head of the judging panel said a new generation of academics must be encouraged to tackle the ultimate challenge of cutting emissions.

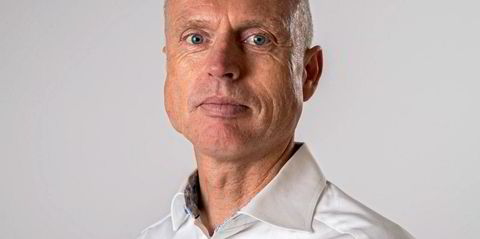

Dr Anthony Papadimitriou, president of the Onassis Foundation, said the reality for modern shipping was that there were no ready solutions to solve the crisis.

He said short-term targets on the road to net zero for shipping by 2050 could be achieved by a mixture of efficiency savings and practices such as slow steaming.

Papadimitriou said Olympic Shipping and Management — the latest iteration of the former Onassis empire — has fitted every available fuel-saving devices on its 18 tankers even when there was not a strong business case.

But these were the low-hanging fruits with the more difficult target of replacing traditional maritime fuels currently out of research for the industry.

He said the shipping prize in the future would look to reward and encourage a new group of emerging academics to take on those challenges.

“You cannot discuss economics, you cannot discuss development, you cannot discuss growth, you cannot discuss shipping, unless we discuss the implications of the climate crisis,” he said.

“So, by necessity, and also by design ... we should focus on that.”

Read more

- Peter Livanos-backed GasLog Ltd gobbles up affiliate after completing merger

- Angelicoussis VLCC sets new Humber River record once held by Onassis Group

- Onassis firm joins Singapore’s GCMD as first Greek member

- Global Maritime Forum reveals location of next annual summit

- Paul Wogan makes way for Enoizi at GasLog helm