Belgian owner Euronav’s emergence as the victor in a UK court battle with UniCredit over a misdelivered cargo claim has led to one leading commodities and shipping law firm questioning if this is the end of the bill of lading (BoL) as the security backbone of a trade finance structure.

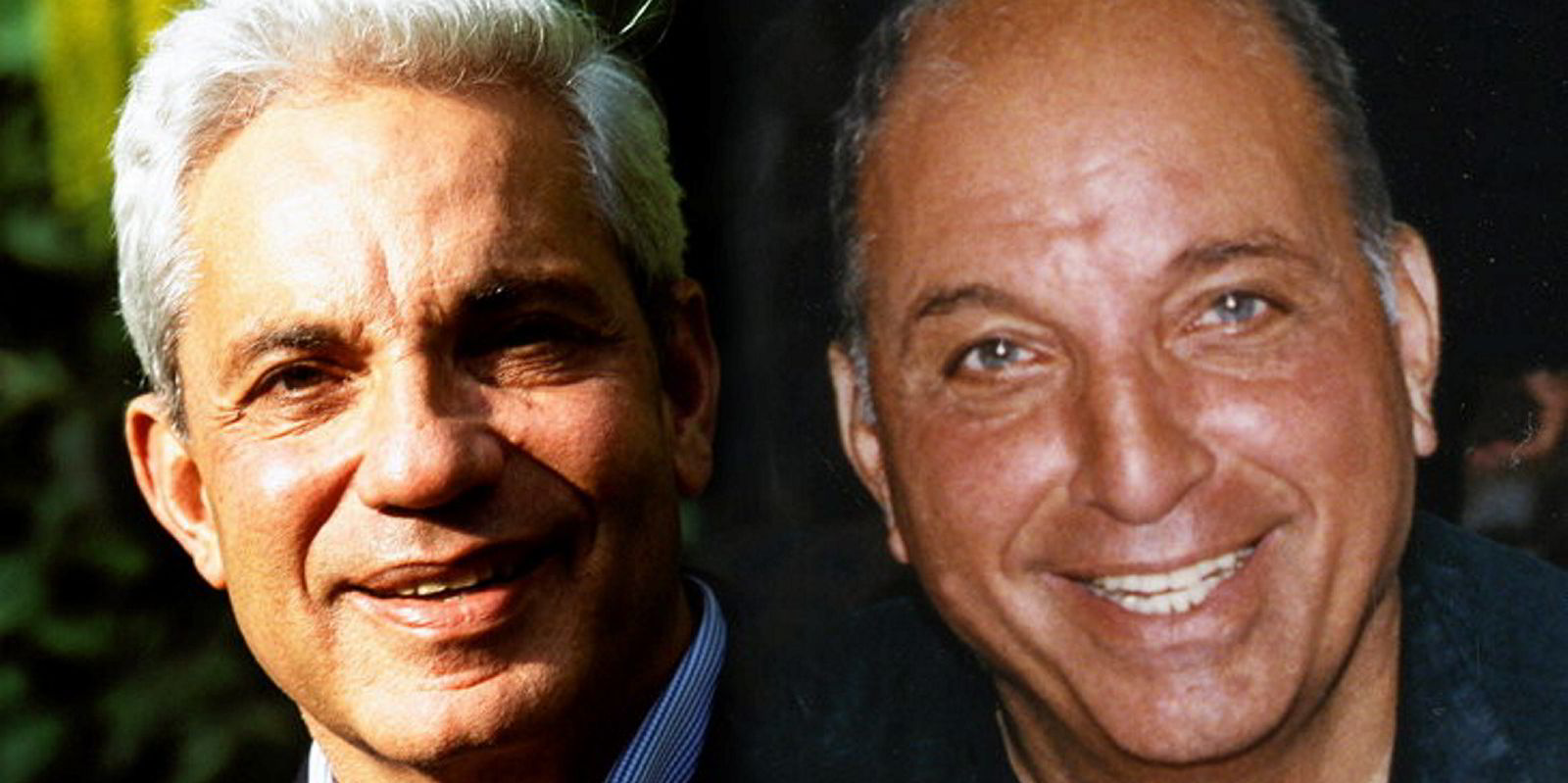

BoLs have formed an integral part of the trade finance structure, according to Baldev Bhinder and Ramandeep Kaur of Singapore-based law firm Blackstone & Gold.

“They are often a fundamental security for banks to receive because they give the lawful holder the right of possession to the cargo and, failing that, the right to bring a misdelivery claim against the shipowner that issues the BoL,” they said in a response to the May dismissal of Unicredit’s appeal.

“BoLs are held by trade finance banks, while cargo can be discharged without a BoL by traders through letters of indemnity. Banks have allowed such practices to continue without objection with the comfort that if all else fails, they can still bring misdelivery claims against the carrier.”

UniCredit tried to recoup $24.7m for a fuel oil cargo carried by Euronav’s 161,000-dwt suezmax Sienna (built 2007) in 2020 that was discharged against a letter of indemnity rather than a BoL.

The Italian bank had financed the purchase by Gulf Petrochem of 80,000 tonnes of low-sulphur fuel oil from BP. Gulf Petrochem ultimately did not pay UniCredit, which in turn brought a claim against Euronav for the value of the cargo, alleging a breach of the contract of carriage by delivering the cargo without production of the BoL.

The claim was rejected by the UK court, which ruled the BoL did not contain any contract of carriage at the time of discharge.

The court found the document was a mere receipt since BP was also the voyage charterer at that time.

A panel of three judges then examined two grounds for appeal put forward by the bank.

The first was that the BoL was indeed a contract because that was the “presumed intention” of the parties at the time.

Breach of contract

UniCredit succeeded on this point, with the Court of Appeal judges ruling Euronav was in breach of this contract.

But the appeal fell down on the second point, the issue of causation. The judges found that if Euronav had refused to discharge the oil because of the missing BoL, UniCredit would have told it to carry on anyway and lost its money in any case.

They noted that it was inherent in the structure of financing and common practice in the oil market for cargo to be discharged without the presentation of BoLs.

The judges rejected UniCredit’s position that it would specifically not have permitted the discharge of the cargo by ship-to-ship (STS) transfers. The bank’s own witness admitted that she was aware the cargo would be discharged via STS and that the original BoL would not be available until afterwards.

Thus, they found UniCredit did not take the view that the conditions of the financing had to be strictly followed since it agreed that the cargo would not be discharged into storage at Fujairah, even though this meant it lost its additional protection of control over storage facilities.

The judges also considered it relevant that UniCredit’s behaviour should be considered against the context where it had no concerns about Gulf Petrochem falling into default at the time. UniCredit had the benefit of insurance covering 90% of the sub-buyer’s default, and it had confirmed sub-buyers were acceptable.

According to Bhinder and Kaur, the case is recasting the fundamentals of trade finance, with the key question now turning to what a bank would have done if it knew a cargo was going to be discharged without a BoL.

“The spotlight is now very much on the banks’ actions and signals greater scrutiny of the treatment of BoLs by banks in their financing arrangements than misdelivery cases have traditionally called for.

“Not every case will replicate the factual matrix of UniCredit, in particular, the court being swayed by the fact that UniCredit was wholly or largely secured in other ways.

A similar inquiry into causation recently occurred in Singapore in a case involving a dispute between Standard Chartered Bank and Maersk Tankers, where the High Court of Singapore examined the underlying financing arrangements and concluded that it was arguable the bank did not regard the BoLs as security.

According to Bhinder and Kaur, Maersk Tankers was found to have raised triable issues contesting the notion of Standard Chartered having regarded the BoLs as security — thus undercutting the bank’s quick recourse to a summary judgment without trial and granting the tanker operator unconditional leave to defend the claims.

‘The message is clear’

In May 2022, Scorpio Tankers also won the right in Singapore to fight OCBC Bank’s claim for a misdelivered Hin Leon Trading cargo after the court examined the underlying financing arrangements and concluded that it was arguable the bank did not meet the threshold for honest conduct required to be a good faith holder of BoLs as it did not look to them as security when it financed the cargo.

Judgments in merit for both cases have yet to be issued.

“The message is clear: if a bank wishes to maintain its security over its BoLs, its conduct with respect to the facility and borrower will have to be consistent with that position,” the two lawyers said. “This leaves a bank in a delicate position knowing that cargo is often discharged without BoLs or not insisting on such a discharge because other types of security are in place.”