Every morning starts for Captain Zhang Deyi at 6.30 am with a hunt for the blood-sucking insects that feast on his body as he tries to sleep on a concrete bed in his tiny prison cell.

He gets through at least two large cans of insect spray a month to battle the mosquitos, cockroaches and flies that enter through the gaps of his barred doors. But his skin is still marked with bites and rashes from the heat in his Indonesian prison.

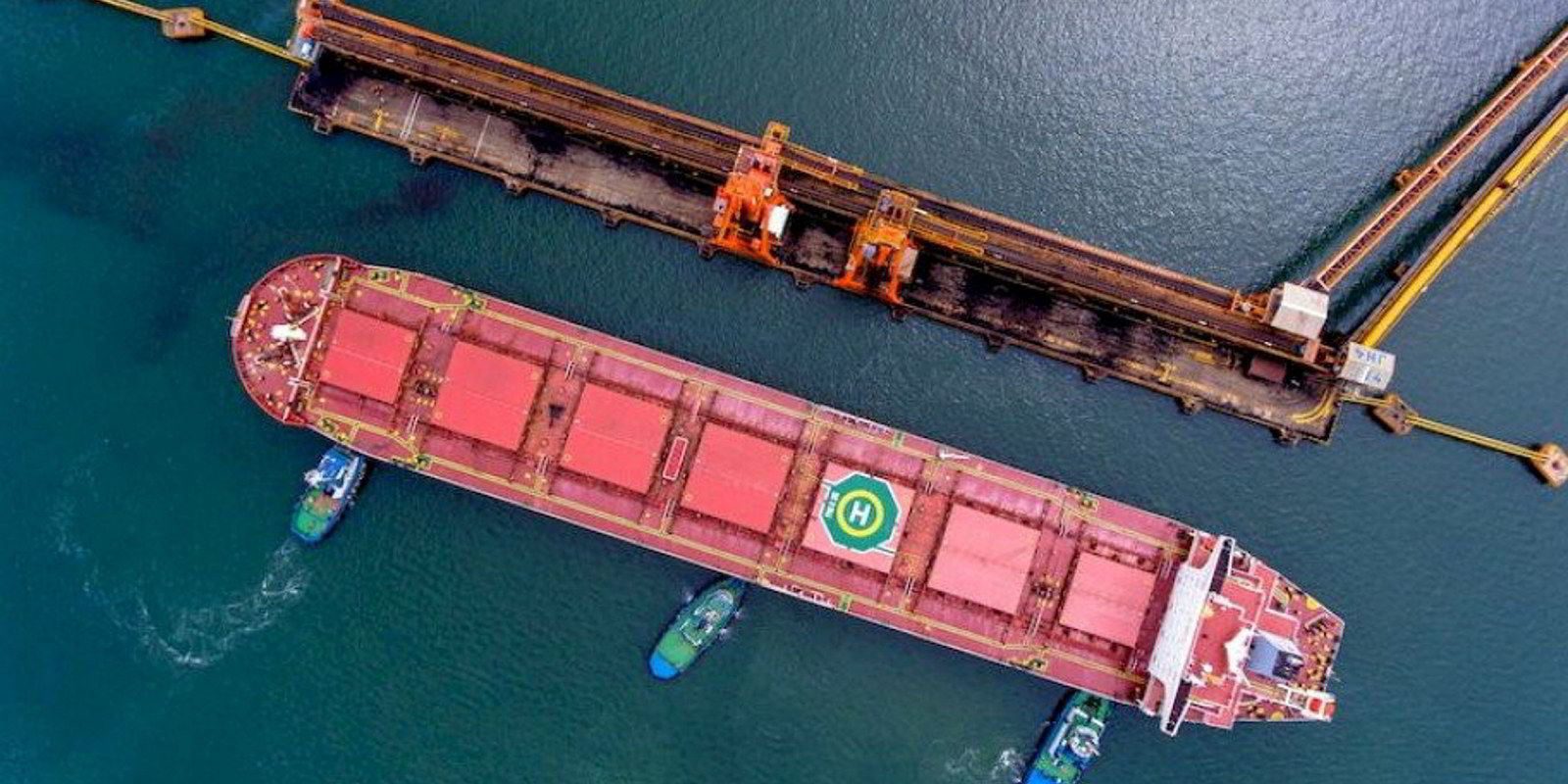

The morning routine is well-practised for Zhang. The former master of the 82,000-dwt Ever Judger (built 2014), a British Virgin Islands-incorporated and Singaporean-managed bulker, has been detained in Indonesia since May 2018.

Zhang has been at Balikpapan prison for the past four years after he was blamed and convicted for a dragging anchor that broke an oil pipeline and caused a leak that went unnoticed for 13 hours. A subsequent explosion killed five Indonesian fishermen.

He continues to proclaim his innocence and his lawyers blame the accident on an under-qualified pilot and powerful state-owned oil company Pertamina for failing to properly protect oil pipes that crossed a shallow bay busy with merchant shipping.

But the buck has stopped with Zhang. Union officials who have taken up his case say his miserable existence in the sweaty, fetid cell is a classic case of seafarer criminalisation that needs to be addressed by maritime administrators.

“The case of Capt Zhang sums up why we need action at the highest level,” said John Wood, of the International Transport Workers’ Federation.

“In more than 30 years I’ve been doing this, I can’t think of any case that has come close to a sentence of this magnitude being passed on a captain.

“Fines, yes, and being held hostage pending payment, yes. But nothing on this scale.”

Zhang’s ordeal started after the Ever Judger loaded a cargo of coal at Balikpapan, in Indonesia’s East Kalimantan province on 30 March 2018.

The local pilot, who was not sufficiently qualified, according to lawyers acting for the owners, told the ship to anchor next to subsea oil and gas pipelines.

Zhang relayed the order to the chief officer but instead of ordering the anchor to be lowered “one metre”, he mistakenly said “one shackle” or 27.5 metres, court papers showed.

The anchor touched the seabed and dragged, damaging a Pertamina oil pipeline and causing the leak. The anchor was rapidly raised but the damage was done.

Lawyers for the owners say the pipeline should have been buried 2.0 metres under the seafloor because it was in such shallow water.

They say the problem was compounded by the failure to have a leak detection system in place, which meant the problem was not spotted immediately.

They claim in court documents that Pertamina was “grossly negligent” and should have known about the leak hours earlier.

But it was Zhang, 55, who was convicted in March 2019, of “intentionally carrying out an act” leading to environmental damage that caused “serious injury or loss of life to others”.

Lawyers acting for the owners said he was sentenced to “10 years in prison for his slip of the tongue”.

He was told he would face a further year in prison if he failed to pay a fine of IDR 15bn (nearly $1m). The court also seized the vessel and its cargo.

‘Complete injustice’

Zhang had his monthly wage of $7,650 stopped on the day he was convicted even though the technical manager, Hong Kong-based Fleet Management Ltd, admitted that he had suffered a “complete and obvious injustice” at the hands of the Indonesian courts, according to emails between the company and the ITF seen by TradeWinds.

Zhang has most recently been reliant on union handouts to pay an elderly Chinese couple to bring him daily rations, he told TradeWinds.

His wife, who suffers from cancer and remains in China, has been forced to go cap-in-hand to relatives for money to pay for her medicine, Zhang said.

She tried to sell their home, but China’s real estate slump meant that they could not find a buyer.

“It can be imagined as a wife of a captain, she felt very ashamed to borrow money,” Zhang told TradeWinds. “She wanted to divorce me because she thought I was a criminal, as Indonesia said.”

He appealed against the conviction to the country’s Supreme Court but that was rejected in December 2019.

His only hope of clearing his name relies on a judicial review of his case using new evidence, not heard at his original trial or appeal, that was dug up by his local lawyer Ponco Nugroho, of the Christie Alliance law practice.

Nugroho says he has obtained a Pertamina document that suggests the oil company secured permission for the pipe to be laid where it was snagged by the Ever Judger’s anchor — but at a depth of 40 metres. Zhang’s team say the pipe was only about half of that depth.

For the captain, this is not fair

— Ponco Nugroho, lawyer

But funding for Indonesia-based legal teams to fight his corner was pulled in 2020, according to Zhang and Nugroho, even as owner Ever Judger Holding Co and commercial manager Everest Shipping fought a $29.2m claim against insurers in London after the ship’s seizure by Indonesian authorities.

The case against the insurers ended with a confidential settlement in 2021.

Ever Judger Holding Co is a single-ship BVI-incorporated company.

“You can only punish someone if he is doing something in his full consciousness … So how come you punish the guy who’s acting beyond his consciousness but you do nothing to the guy from the company that lays the pipe in the port?” Nugroho said.

“That’s the place where vessels are dragging their anchors, dropping their anchors. It’s a place for vessels, not pipes.

“For the captain, this is not fair.”

He said he found an expert witness who cited an academic paper that suggested everyone performs a “slip of the tongue” seven to 22 times a day.

“This captain is doing a nevertheless common and almost inevitable thing that people do but he did it at the wrong time, in the wrong position, in the wrong system,” Nugroho said.

‘Safety failure’

Lawyers acting for the owners denied the ship was at fault in their defence of a civil case brought by Pertamina in Indonesia over the cost of the clean-up.

“This case is about basic safety failure at Balikpapan,” said lawyers acting for the ship’s interests and Zhang in an August 2019 defence document seen by TradeWinds.

“Four subsea distribution pipelines were left unburied, unprotected and incorrectly shown on the navigation charts while ships pass over them every day.

“Further, the ships waiting to load at the plaintiff’s [Pertamina’s] refinery drop anchor in and around the pipelines every day.”

It went on: “A failure to put basic safety systems in place turned a minor maritime incident into an environmental crisis.”

TradeWinds has approached Pertamina for comment but officials could not be reached.

The failure of an appeal in Zhang’s criminal case to Indonesia’s top court was followed by Nugroho writing to his client in March 2020 to say that nobody was willing to fund any more efforts to clear his name.

Payments for prison food and toiletries were stopped at around the same time and he now has to foot the bill of more than $500 a month himself.

“It seems like they didn’t need me any more,” Zhang said.

Maritime lawyer Stephen Askins, who is not connected with the case, said it depended on the owner if a master would be paid wages in cases where seafarer criminalisation was claimed.

Protection and indemnity clubs, responsible for third-party claims, would normally pay a master’s legal costs until conviction, he said. After that, it becomes more difficult for the clubs as they cannot indemnify in cases of illegality.

“How a crew member or a master is treated comes down to the owner themselves,” said Askins, a partner at London-based law firm Tatham & Co.

“There are not any hard and fast rules. It really depends on who the owner is.”

Zhang has received few visitors in jail but was visited last year by Peter Astbury, the managing director of Arundel Resolution, a company focused on “resolving complex, seemingly intractable problems” in the maritime sector.

He was appointed by the Ever Judger’s P&I club, The West of England, to travel to Indonesia a few months after the incident in 2018 in an unsuccessful attempt to secure the release of the ship and the captain and resolve the crisis amicably.

Astbury returned on his own volition last year because “I don’t like leaving people behind”, he told TradeWinds.

I don't like leaving people behind

— Peter Astbury

He met Zhang several times at the prison to understand what he could about his situation and reported back to the P&I club.

The ITF also became involved last year after Zhang wrote to it from his cell.

John Wood, a campaign adviser for the ITF, wrote a series of letters calling for action from the owners to support efforts to clear Zhang’s name.

He has called for Zhang’s wages to be paid in full until he is released and repatriated.

Four months after Wood first made contact, Zhang received a financial offer from the owners, via the P&I club and Astbury, for a $800-a-month settlement from the date of his conviction to his release — but only if he agreed to drop any claim against his employers and kept the deal secret, according to a document seen by TradeWinds.

Wood criticised the offer — amounting to little more than a 10th of his monthly wage — and said it had only been made because of pressure from the union.

The West of England club declined to comment on detailed questions from TradeWinds as it was a complex and sensitive case.

But it said that its members were “making efforts through local lawyers to enable the master’s release”. It added that it was maintaining contact with the ITF over the issue of Zhang’s welfare and wages.

New local lawyers visited Zhang for the first time this month when he agreed for them to represent him. They also wrote to Wood in February to say they were preparing to submit a judicial review challenging the previous ruling against Zhang.

Fleet Management, a member of the International Maritime Employers’ Council, said it had struggled to find any law firm since December 2019 “capable of finding ways to enable an early release of the master”, according to emails from the company’s executive director to the ITF.

A spokesperson for Fleet said it was unable to comment in detail given the sensitivity of the case. But it said legal efforts in conjunction with the owners were being made to secure the captain’s release. “We continue to keep in close contact with the ITF,” the company said.

Wood said the case highlighted the need for improved regulations to ensure that seafarers subject to unfair treatment were better protected.

“In putting forward an argument to support the introduction of legislation to prevent the criminalisation of seafarers involved in accidental maritime disasters, it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to present a better case than this,” he said.

David Hammond worked on similar cases for a decade after founding the Human Rights at Sea (HRAS) charity, before stepping down to run a maritime investigations group, Human Rights at Sea International.

“The criminalisation of seafarers and masters when matters on board vessels went wrong, or were under investigation by the flag or coastal port authorities, came across our desk regularly,” he said.

Hammond said the current system stopped seafarers from properly clearing their names. “Our focus [at HRAS] was to investigate those cases and bring them to public view.

“We were often stopped because of correct due process … the majority were confidential settlements with non-disclosure agreements attached.

“They were also complicated by the fact that the individuals involved were put under a strong degree of pressure not to be public about what happened and they were in fear for their future professional employment.”

Nugroho said that Zhang could have been released in December last year under time-served rules if the $1m fine had been paid, although he would have had to spend months longer in Balikpapan before being allowed to return to China.

The failure to pay the fine will delay Zhang’s release by a year, Nugroho believes. Any judicial review would take at least a year and he should be out before it was completed, Nugroho said.

But for now, Zhang will remain at Balikpapan jail and continue his evening routine of hunting for mice and insects in his cell before watching TV and then taking a shower before lights out.

The support from the union has at least convinced his wife that her husband is innocent and the pair are reconciled, albeit in different countries.

“We are human beings and not God,” Zhang told TradeWinds. “So there are human errors during our work that cause an incident, which we really don’t want to happen.

“But the Indonesian criminal court conviction is a complete miscarriage of justice. I am going to tell every seafarer that I meet for the rest of my life that Indonesia is a terribly dangerous country.

“Be careful, you are risking your life if you go to Indonesia.”

Read more

- Russian master back home as oil smuggling probe drags on

- Drugs menace has become seafarers’ worst nightmare, Intercargo warns

- Jailing masters harms fight against drugs trade, warns ICS

- Criminalising an officer’s honest mistake sends the wrong message

- Master’s detention reflects ‘growing criminalisation’ of seafarers

- Would a hotline help? Shipping seeks answers to seafarer criminalisation