An age-old question looks closer to being resolved following a recent court decision: what makes or does not make a floating craft a ship?

A ruling by a High Court of Singapore judge in a contract payment dispute has provided a threshold definition under the country’s laws.

The ruling stems from moves by Singapore’s Aquaculture Centre of Excellence (ACE) to throw out Vallianz’s March arrest of its floating fish farm Eco Spark by claiming that the converted barge could no longer be legally defined as a ship.

The company argued that the Eco Spark is not a “ship” within the meaning of Singapore’s High Court Admiralty Jurisdiction Act and therefore should not have been arrested as the requirements for invoking the court’s admiralty jurisdiction had not been satisfied.

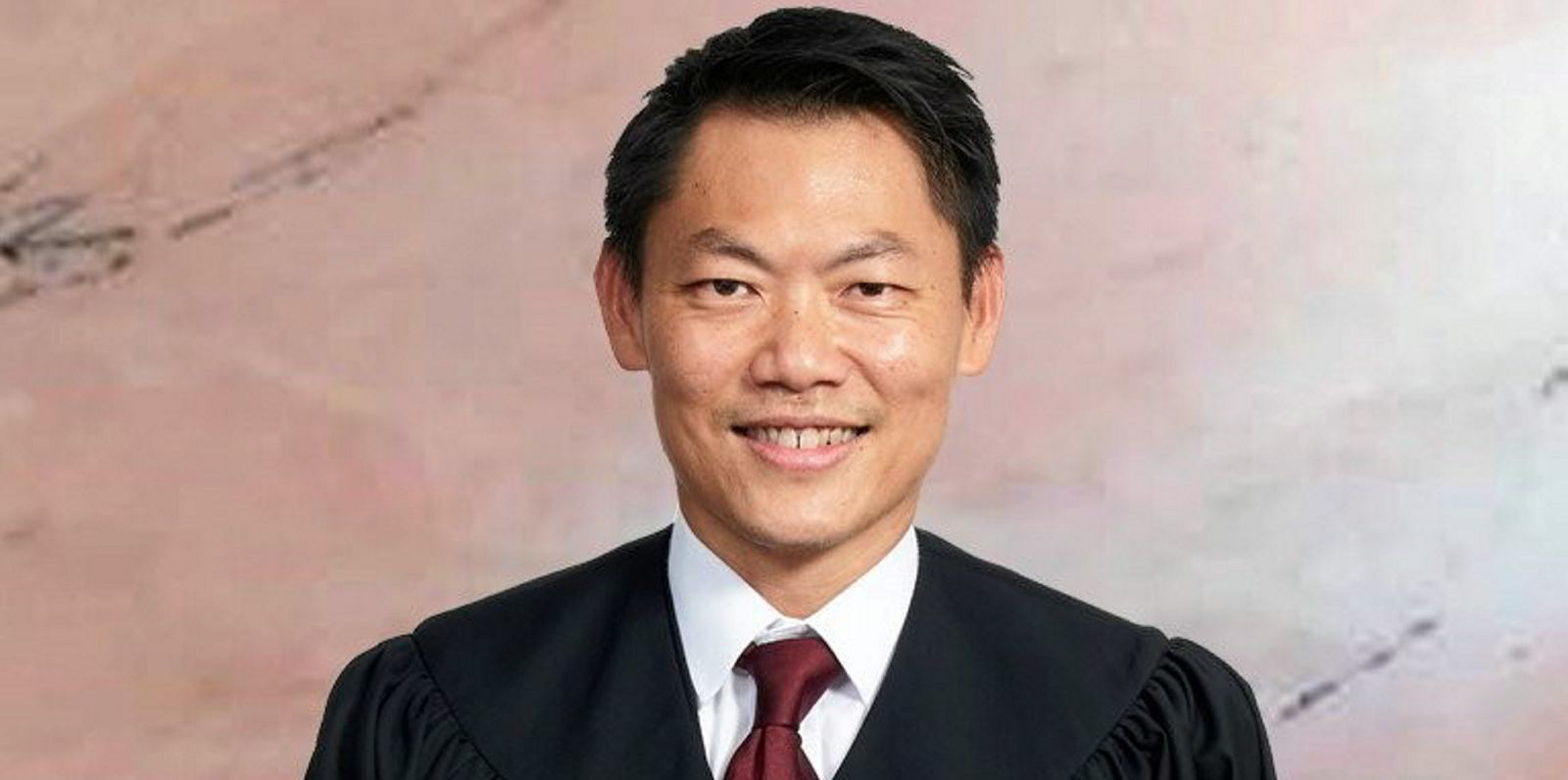

Justice S Mohan found that the Eco Spark was a “ship” within the meaning of the act, and therefore the admiralty jurisdiction of the court was properly invoked by Vallianz.

“While the vessel does not possess a number of the ‘usual attributes’ associated with a ship, I do not regard the absence of those attributes as representing such a drastic departure as to disqualify the vessel from being considered a ‘vessel used in navigation’ and thus a ‘ship’,” he ruled.

In his ruling on the matter, Mohan said that both the plaintiffs and defendants took a “kitchen sink” approach to the question of whether the Eco Spark was a “ship” by raising a multitude of characteristics of the vessel, both present and absent, in support of their respective positions.

ACE argued that the Eco Spark has no rudders or engines and is not capable of self-propulsion. It does not have any navigational equipment or lights and is not manned by a seafaring crew. It does not transport any person, cargo or object.

Since its installation on 28 February 2022 at the farm site off Singapore, with three spud legs embedded into the seabed, the Eco Spark has become a stable, immovable fixture, and it will remain immovable for the duration of its operative life as a floating fish farm.

ACE went on to argue that the Eco Spark is not registered to any flag state, is not classified with any classification society and does not pay any port dues. It operates under a licence issued by the Singapore Food Agency and is an approved structure erected within the farm site under a Temporary Occupation Licence granted by the Singapore government.

The company argued the Eco Spark was towed from Vallianz’s shipyard on the Indonesian island of Batam for the sole purpose of bringing it to the farm site where it was to be installed, and it was for this reason that classification society Bureau Veritas issued it with a certificate of survey for the single voyage.

The Eco Spark, ACE added, was constructed for the purpose of being a sea-based fish farm and was not designed or constructed to be capable of traversing significant distances on the surface of the water. And the company said it was not intended that any significant part of its function was for it to be used in navigation.

Vallianz, an offshore vessel company and shipbuilder, argued that the Eco Spark was a barge before its conversion and that it remains a barge in nature and functionality.

A barge, the company pointed out, need not be self-propelled or have engines, and this does not affect its classification as a vessel or ship.

The Eco Spark, Vallianz added, already had spud legs prior to conversion, at which time it was flagged and classed as a ship. The placement of the spud legs in the seabed does not make the vessel immovable or a permanent fixture as they are removable and retractable.

Vallianz said the contract stipulated that the Eco Spark would be converted under Singapore flag requirements and in full compliance with Bureau Veritas’ requirements, and although it is not currently registered under any flag state and has not maintained its class status, registration is not determinative of whether the vessel is indeed a ship.

Finally, Vallianz argued that the Eco Spark is similar to an oil rig in that it is designed to exploit natural resources from the sea, and oil rigs have been held to constitute ships even though they are fixed to the seabed.

It’s a ship

When making his determination that the Eco Spark is a ship, Justice Mohan said that at the core of the matter was whether definition of “ship” under Singapore law included “floating craft of every description used in navigation”.

“It might come as no small surprise to some but this deceptively simple question is one to which there appears to be no clear (and some might argue, consistent) answer in the wealth of jurisprudence on this topic amongst the courts in the commonwealth,” he said.

“A significant number of English decisions have dealt with the question of what makes a vessel a ‘ship’ but they do not all speak with one voice. Some of the earlier cases suggest that the assessment of whether a vessel is ‘used in navigation’ looks to its actual use, while cases decided more recently suggest that the answer depends on whether it is designed and capable of being used for navigation, irrespective of the actual current use.”

Justice Mohan added that the question of whether a vessel or structure is or is not a ship within the meaning of Singapore’s admiralty law is a question of jurisdictional fact to be established on the balance of probabilities.

“One of the core facets of the definitional inquiry before me is whether the court should have regard to the design and capability of the vessel to be used in navigation, as opposed to the actual use and frequency of use of the vessel in navigation,” he said.

According to Justice Mohan, the actual current use of a vessel, even if relevant, should not be determined by whether its operational work is executed while in navigation. What is important is the vessel’s capability to be used in navigation.

The Eco Spark, he said, was previously a steel dumb barge capable of being used in navigation and fell within the definition of a “ship”. For all intents and purposes, the basic design and structure remained unchanged after conversion. That it could be safely towed from Batam to Singapore showed that it was still capable of navigation.

Furthermore, he noted that the conversion contract stipulated that the hull of the vessel would be assigned the Bureau Veritas classification notation symbol of “I+ Hull Special Service – Floating Fish Farm, Coastal Area”.

“On the evidence before me, I am of the view that it was expected that the vessel would not only comply with BV’s requirements for the duration of the conversion works and towage from Batam to Singapore but also throughout the course of her usage as a floating fish farm,” the judge wrote.

The judge added that it was a Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA) requirement that floating fish farms be built under the survey of the classification society and remain in class throughout their use in such a role in Singapore waters.

The fact that the Eco Spark had not maintained its class status was attributable to ACE’s failure to do so, and not because it is incapable of being classed, he found.

“The fact that the MPA, as the maritime and port regulator, required the vessel to be classed and maintained in class, and that BV itself recognised that such special service floating structures as the vessel are ships, also point to the vessel being a ship,” he said.

Justice Mohan also dismissed ACE’s claim that the Eco Spark was a fixed structure secured to the seabed. He noted that the vessel’s spud legs could be raised, and it was capable of being safely towed to another location if need be.

He characterised the case as answering a “threshold” question on the definition of a ship.

“This case therefore affords an excellent opportunity for me to consider the available caselaw both here and elsewhere, and attempt to distil from them some general principles for the benefit of the admiralty Bar, not least so that the proverbial ‘elephant’ might be easier to define in future cases,” he said.

Vallianz and ACE are resolving their dispute through arbitration under the Singapore Chamber of Maritime Arbitration.