Shipowners could once count on disposing of assets so that they stayed disposed. But, today, disposed assets can come back to bite you — and knowing a vessel’s buyer is a growing part of the cost of doing business responsibly.

It is a cost that is going to keep rising, and the owners of physical assets such as ships will be the ones to bear it, thanks to sharpened environmental and corporate governance requirements.

Not least among those is the cost of due diligence in avoiding exposure to international trading sanctions.

Ask the owners of the 51,400-gt Bolette Dolphin (built 2014). A consortium of bankers and investors is trying to get rid of the drillship after three-and-a-half years of unemployment.

Danske Bank, DNB, SEB, Swedbank and Strategic Value Partners thought they had found a buyer for the technically sophisticated and unloved former Fred Olsen Energy asset.

But the prospective buyer’s money may not be good enough, according to Oslo business daily Finansavisen. Selling to Turkish Petroleum Corp could run foul of European Union sanctions imposed on two company executives over gas exploration off Cyprus.

Heartbreak in the headlines

When an asset ordered for $615m turns out to be worth $90m after years of unemployment, and when, even then, sanctions make the prime buyer ineligible, the heartbreak makes headlines.

But even in smaller deals, the depression is a general one. Selling ships responsibly in the 2020s entails pitching them to a shrinking universe of potential buyers. A smaller pool of buyers inevitably tends to lower prices, or potentially to force early scrapping.

Every owner of a ship or other wasting asset during each segment of its lifetime has to make assumptions about who the very last owner and user of the asset will be, as a routine part of the value calculation.

But today, the basis for those assumptions is changing — and it is going to change more.

Selling ships responsibly in the 2020s entails pitching them to a shrinking universe of potential buyers, which inevitably tends to lower prices or potentially to force early scrapping

One shipping lawyer observed not long ago that there are three types of buyer for vessels of a certain age: cash buyers in the last resort; small private purchasers in certain regions that specialise in squeezing the last dollars out of veteran tonnage; and buyers that intend to turn off the AIS and trade with countries under US sanction.

But all three of those categories are under pressure.

In scrapping sales, a shipowner whose vessel ends up on a beach after sale may find that it has run foul of European law — or, if it is a listed or high-profile owner, that its environmental irresponsibility has made it a pariah to institutional investors, equity markets and banks.

In sales to marginal operators, owners in several countries have become pickier, partly for regulatory reasons. China, not long ago a reliable market for bulkers approaching scrap value, has imposed age ceilings for domestic-flag imports. Even owners in the international-flag coal and nickel trades have begun turning up their noses at their traditional staple: ageing Japanese-built bulkers.

Asset afterlife

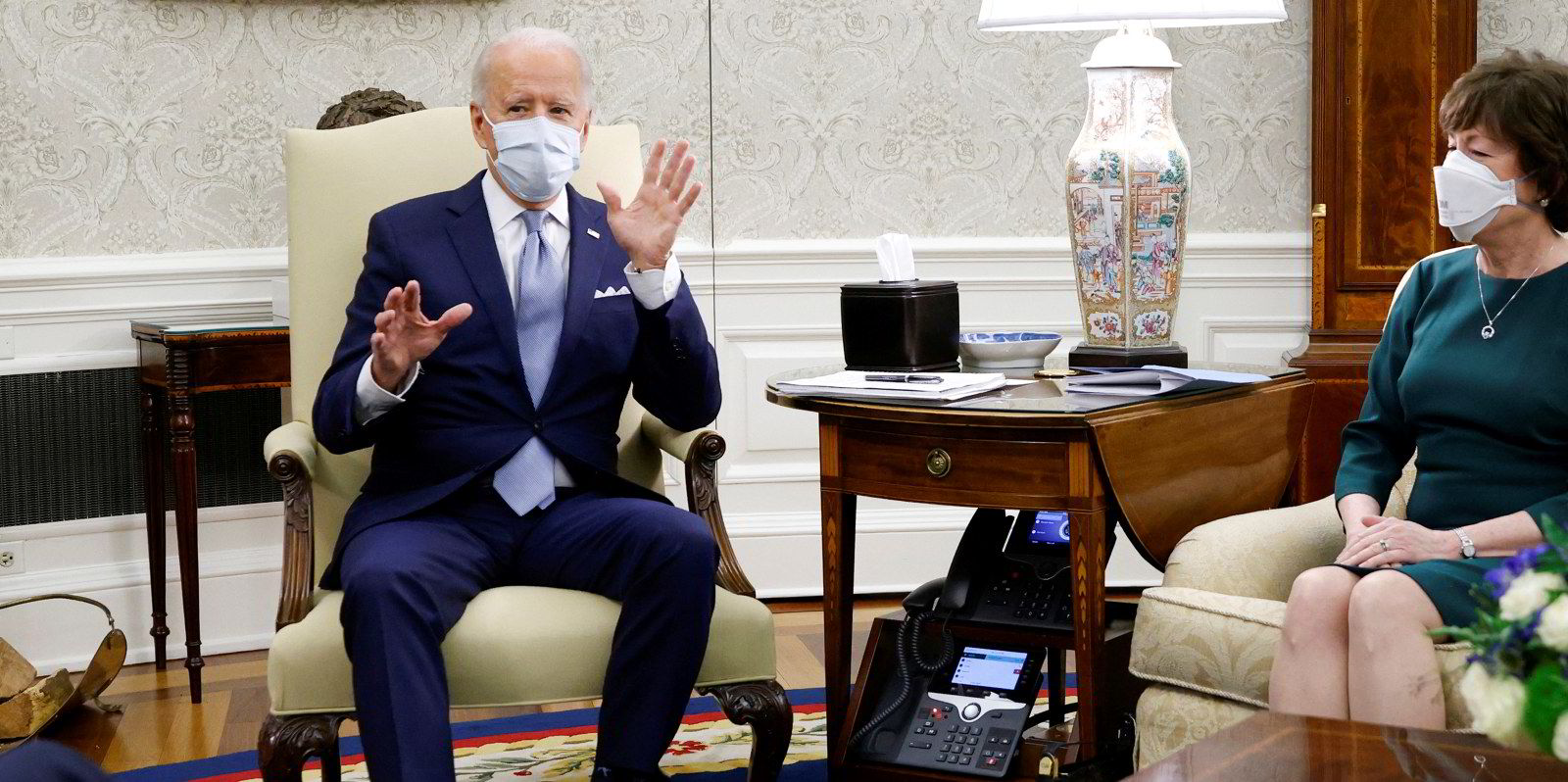

In the sanction-flouting trades, US enforcement has not shied away even from Chinese state-owned companies. And those who expect a lighter touch from the new Biden administration risk getting a bit ahead of their own game.

The need to mind the buyer in scrapping transactions is already well known and has inspired a growing industry of green scrapping companies, which urge that if a ship ends its lifespan as an environmental problem, it does not matter how responsibly its owners managed it during the middle of its lifespan.

The same principle may apply more generally now as banks, investors and governments insist on greater insight into the post-transaction afterlife of assets.

Some day, the environmental and governance costs are bound to be priced into the value of new ships. But until that time, asset sellers all along the chain — and not just at the end — will have to face the fact that they must foot the bill in the form of reduced residual and resale values.