IMO 2020 is fast approaching and will have far-reaching consequences for shipping and world trade.

The motives behind a curb on high-sulphur fuel emissions are commendable. If alternative, environmentally friendly fuels are available, then shipping should strain every sinew in cutting needless pollution.

However, the inflexibility of the guidelines and high compliance hurdles are leading to solutions that are unlikely to benefit the planet and, worse, may place a dramatic strain on the arteries of world trade.

2020 warning

This article is a warning that scrubbers and slow steaming are not the answer.

IMO 2020 comes into force on 1 January and the central tenet is a 0.50% global sulphur cap for marine fuels. Thus, vessels will have to use fuel with sulphur content that must not exceed 0.5% against the current limit of 3.5%.

While the oil majors have reported alternative compliant fuels, many companies have turned to scrubbers, with much accompanying discussion.

In essence, it involves a mechanism for using high-sulphur fuel oil (HFSO), rather than a lower, potentially more expensive sulphur-compliant option, to be scrubber filtered.

The ultimate scrubber filter switches from the air to the sea. The hedge is obvious to the investor or shipowner and for a short period those with scrubbers may see a dramatic saving in their bunker costs.

However, it does not take specialist scientific knowledge to spot the flaw.

If the industry thinks that the problem of unacceptable air pollution can be solved by putting that pollution via a filter into the sea, then they can expect a tremendous backlash from environmentalists and the wider public.

What is the point in extensive operations to clear the sea of plastic, if HFSO pollutants are now pumped into the oceans?

Slow steaming is the second option with significant publicity. In brief, this is the practice of operating ships below maximum speed, thus reducing fuel costs.

This proposal is inherently counter to fast moving world trade and growth. What is the point in a 5G network or Ultrafast broadband if the good you purchase online takes longer to reach you?

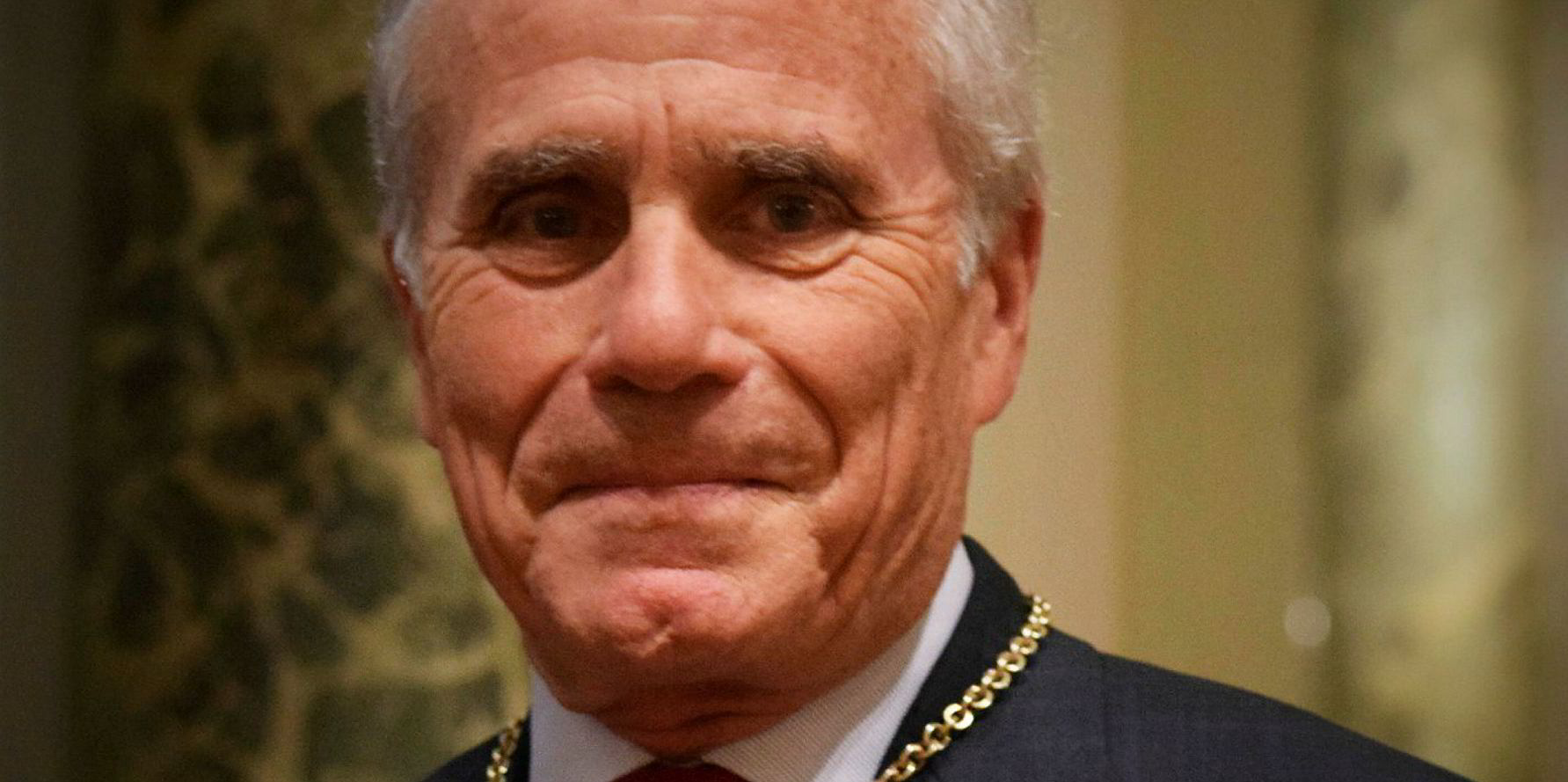

George Gross

AP Moller-Maersk adopted this method after the 2008 financial crisis and Clarksons’ data covering the last decade shows that vessel speeds fell by about 21% across all vessel types, slashing total fuel consumption and CO2 emissions by 18%.

Slow steaming

In a 2014 IMO report, slow steaming was seen as a major factor in reducing CO2 emissions, with ships contributing 2.8% of total greenhouse gases in 2007 and 2.2% in 2012.

Over this period, average speeds fell by 12% and fuel consumption 27%. Therefore, those such as Louis Dreyfus Armateurs feel this is a solution to IMO 2020.

Yet again the problem is obvious. This proposal is inherently counter to fast-moving world trade and growth.

What is the point in a 5G network or ultrafast broadband if the goods you purchase online take longer to reach you?

To our navigational trading ancestors, who discovered the sea routes of the world, the idea of getting from A to B more slowly would have been an anathema.

It simply will not do and if companies find their goods take longer to reach their customers, then they will find alternatives.

Higher rates are also likely with fewer round-trip voyages and there are also potential issues of cheating and compliance.

Higher rates may appeal to shipowners, but they do not suit consumers or retailers, with longer freight times and higher costs.

Shipping may take about 90% of world trade, but it does not possess divine right and the industry would have only themselves to blame if this figure were reduced by aviation or other transport types.

What is the solution? Again, it is not dramatic or far-reaching. The solution is an alternative lower-sulphur fuel at a reasonable price

Such alternatives may be even less green-conscious, but you cannot stand in the way of progress and slowing world trade by slowing vessel speeds is precisely that. There will be consequences.

Escalating costs

Goldman Sachs estimates IMO 2020 and more expensive fuel oil will cost shipping operators about $50bn, yet the industry “does not have a financial war chest to cover [such] an escalating cost”, as Bimco chief shipping analyst Peter Sands has commented. Therefore, the cost will be passed on.

So how can this be mitigated? What is the solution? Again, it is not dramatic or far-reaching. The solution is an alternative lower-sulphur fuel at a reasonable price.

This should have been the IMO’s top priority and to have left it to the industry to solve is remarkable.

A collaboration with the oil majors is needed and if necessary, a phased compliance period, rather than an arbitrary date that will see an unsavoury option adopted.

There is still time, but it must be used wisely and with haste.

George Gross is an analyst at Christofferson, Robb & Co

and visiting research fellow at King's College London University.