As the COP28 climate talks rumbled on in Dubai, a room full of policymakers, trade union officials and shipping folk met at the Palace of Westminster in London to discuss decarbonisation.

The event was the latest in a series held by the makers, including myself, of The Oil Machine film who wanted to throw an audio-visual pebble into the debate about how to find both clean energy — and security.

Leading economist Ann Pettifor, a member of the Scottish Just Transition Commission, explained the short-term interests and dangers of speculating in the financial and oil markets.

Others called for more public ownership and decried continuing hydrocarbon licensing while warning that the threat of closure at the huge Grangemouth refinery near Edinburgh was a pointer to the threat to jobs of declining oil demand.

But it took a shipbroker, Hugo Wilson from Affinity (Shipping), to ask the pertinent question: “So which country has adopted the kind of model on decarbonisation that could be followed by the rest of us?”

The room was stumped. While some praised Norway for doing so much on renewables — and I would have put forward Denmark for encouraging industrial leaders such as Vestas, Orsted and AP Moller-Maersk — few countries, it was agreed, were showing the way.

The UK has a Climate Change Act but is licensing new oilfields and coal mines, while the US has a massive green energy investment programme but is expanding its hydrocarbon output daily.

In terms of the justice side of the equation, the room finally came down to the historic example of the tiny islands of Shetland — a Scottish archipelago halfway between the Faroe Islands and Norway — where the local community obtained a strong financial package with the oil industry in return for development of the Sullom Voe terminal.

Even today, there are still excellent social services on Shetland at a time when many other parts of Britain have seen only decline. Still, we may conclude that the future must come from our imagination.

And if free market governments can pay people to stay at home and not work, as happened during Covid, then things can certainly change in the face of extreme threats.

The problem is, many people feel able to discount the climate crisis as an extreme threat — even after 8m Pakistanis were forced to leave their homes and 33m were directly affected by flooding last year.

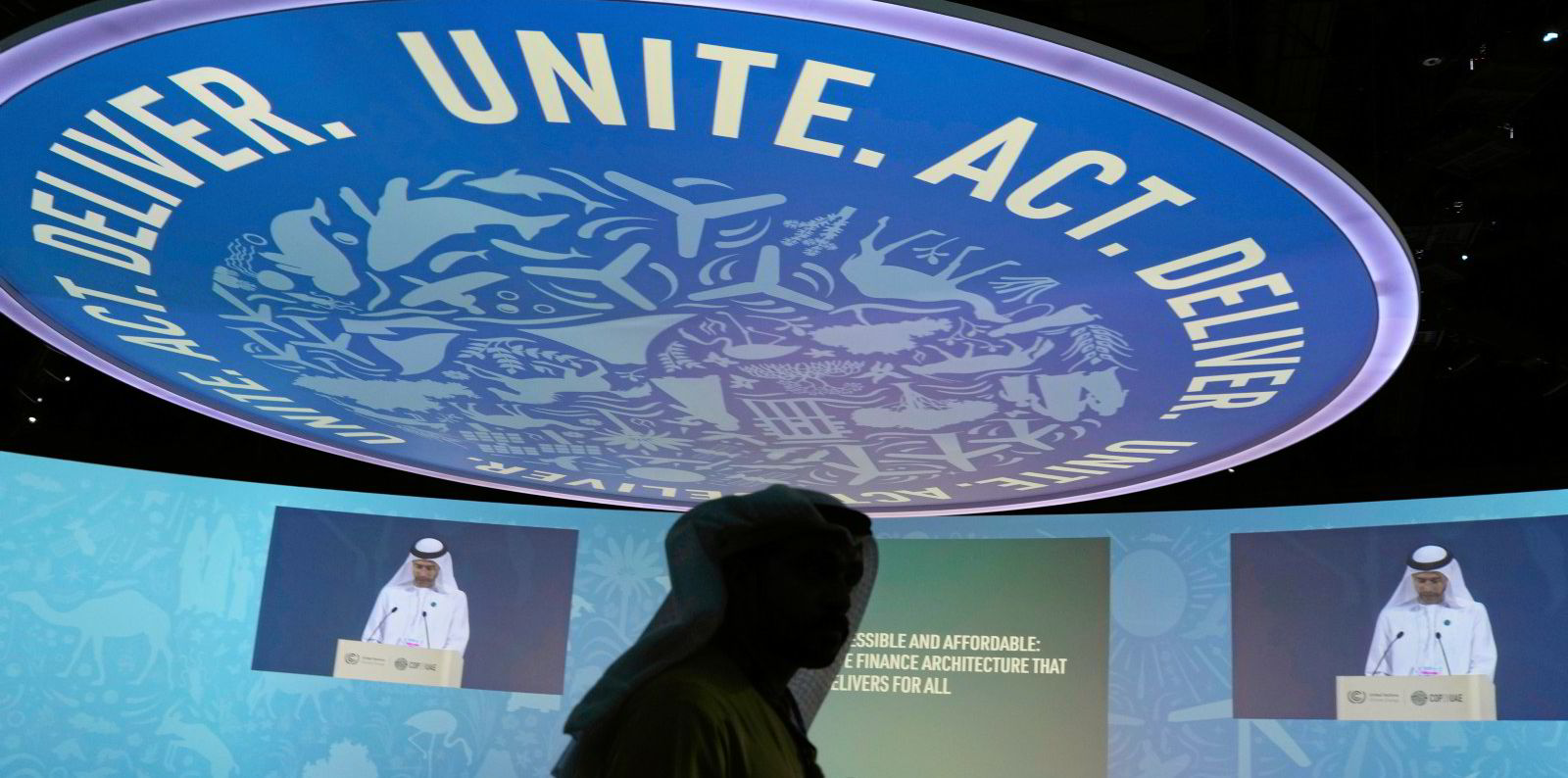

There have been 28 climate talks by the United Nations’ Conference of the Parties, or COP, but so far the words “fossil fuels” have not been entered into any final text. Will this year be different?

While these texts might stumble, many businesses see the need for change and want policymakers to buck up. Five years ago, you could not have imagined five leading container ship operators making a plea for a date to phase out fossil-fuelled vessels.

There have been 28 COP climate talks, but so far the words ‘fossil fuels’ have not been entered into any final text. Will this year be different?

It’s the equivalent of being paid by the government to stay at home for the chief executives of CMA CGM, Maersk and others to demand a course of action that will cost them a lot of cash — but it will help secure our long-term futures.

A recent World Economic Forum report says the total bill for constructing new or retrofitting existing ships for zero CO2 emissions could be $450bn.

But as Rolf Habben Jansen of Hapag-Lloyd put it: “A regulatory framework and clear targets are crucial to accelerating the introduction of alternative fuels.”

In the meantime, some shipowners are voting with their feet — or wallets. More than 150 newbuildings able to use potentially no-carbon methanol as well as diesel in their main engines have been ordered so far this year, according to class society DNV.

Other owners still argue it’s unfair for them to be expected to move into “clean” fuels, with or without regulation, until bunker suppliers can assure them there will be enough to go around.

And there are still arguments that the European Union’s Emissions Trading System, scheduled to apply to shipping on 1 January, will just drive traffic away from continental ports as owners re-route to dodge tax.

So there are loads of tricky questions, whether in Brussels, Dubai or London, but carbon emissions keep on rising along with extreme weather conditions. The Oil Machine grinds on.