Let’s start with the good news. It won’t take long.

A leak of documents has revealed there is insurance cover in place for some elderly tankers hauling Russian oil around the coastline of Europe — and we know who is providing it.

The bad? It might not count for much.

That’s the conclusion to be drawn from marine insurance documents, seen by the Financial Times and Danish journalism outfit Danwatch, that suggests that Russian insurer Ingosstrakh is covering some of the dozens of tankers dropped by Western protection and indemnity providers owing to concerns of breaching sanctions rules.

But while many of those vessels are likely to be carrying Russian oil priced above the cap — and thus breaching Western sanctions — the company has an exclusion clause that requires Russian exports to comply with applicable US, UK or European Union laws.

The company told the FT and Danwatch that it reserved the right to cancel cover for vessels selling Russian oil above the price cap, of $60 a barrel of crude and $100 and $45 for refined products.

The price of Russian Urals, the main export grade, surged above $77 a barrel in mid-March, according to Trading Economics. The International Energy Agency said exports from Russia’s Far Eastern port of Kozmino in February were about $10 a barrel more than Urals.

On that basis, there’s not a lot of price-capped oil on the water. So in the event of a spill in Europe or elsewhere, who would pick up the tab? The likelihood is that it wouldn’t be Russia.

European coastal nations have previously warned that they would be left to pick up the cost of a clean-up along with the International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds, known as IOPC Funds.

If an uninsured tanker — or one covered by an insurer incapable of paying — was involved in a major spill, then IOPC Funds is likely to be on the hook for the full cost of pollution compensation. Its head has warned of the “negative side effects” of the sanctions.

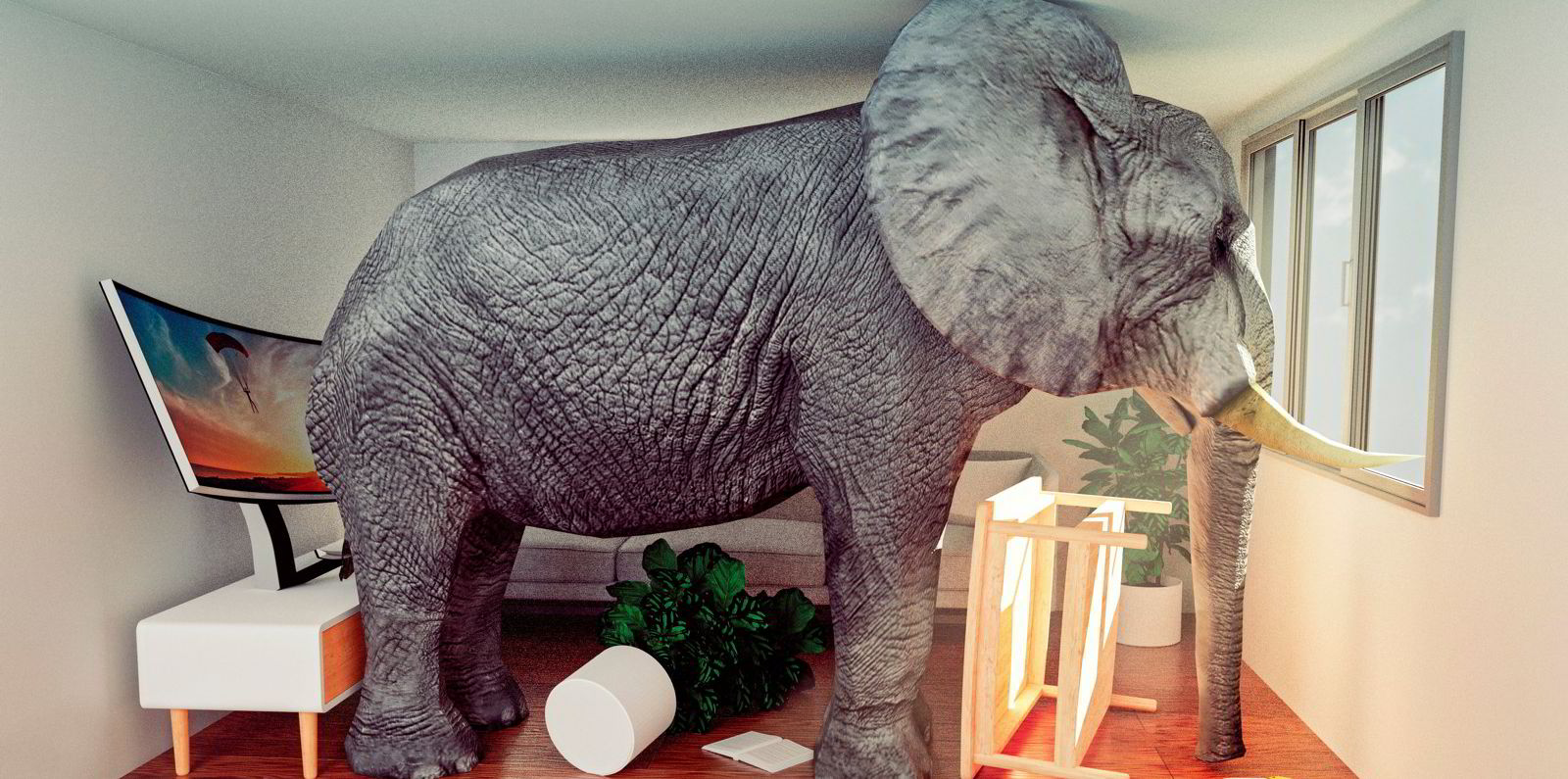

And with the so-called shadow fleet’s growth to more than 700 vessels — tankers typified by complex ownership and inadequate insurance while hauling sanctioned oil cargoes — there’s only so far that a policy of crossed fingers and hoping for the best will go.

Up to now, the world has largely got away with it. The 96,800-dwt aframax tanker Pablo (built 1997) was not carrying oil when it exploded on 1 May 2023 off the coast of Malaysia.

Uniquely at risk

TradeWinds has reported on the case of the 53,100-dwt product tanker Canis Power (built 2005), which lost power in a busy shipping lane off the coast of Denmark with 340,000 barrels of Russian oil on board.

It strayed from a narrow shipping channel in the Danish Straits, nearly running aground before reaching deeper waters for repairs. The ship had just changed P&I provider and details of replacement coverage were hard to come by.

About six months later, its operator at the time, Radiating World Shipping Services of Dubai, was hit with sanctions by the UK government. After a peak of operating 17 tankers in 2023, Radiating World is now down to two, according to Equasis.

The Danwatch report found that 191 tankers from Russia sailed through the Danish Straits from 1 December 2023 to the end of February. Of those, 140 did not have recognised Western insurance, which provides the vast bulk of P&I cover for the world’s tankers.

A report by Denmark’s National Audit Office in January provided little comfort if the worst should happen. The country is uniquely at risk given the narrow shipping lines, navigational difficulties and vast sea traffic that passes around it.

The report noted that the Swedish coastguard had expressed concern last year about an increased risk of oil spills owing to the elderly fleet of Russian ships.

It found that any emergency response would not be fast enough, have enough resources or have the ability to combat certain oil and chemical spills.

Four emergency response ships that would lead any crisis response were deemed obsolete in the mid-1990s. Officials had long been aware of this critical situation, yet replacement vessels will not be available until the 2030s.

The Danes can only hope that such a spill will not come to pass. And cross their fingers.

Read more

- Sanctioned Sovcomflot facing ‘operational difficulties’ from US crackdown

- Russian petrochemical exports under threat after mass attacks on refineries

- Sanctioned Sovcomflot tankers switch tactics as they discharge cargoes in China

- d’Amico International boosts dividend further on record annual profit

- What latest Russian refinery attacks mean for tankers