Myanmar is under threat of new sanctions that could affect investment in its shipping sector after the military coup on 1 February that removed Aung San Suu Kyi's civilian government.

Sabres are rattling in the US and European Union, but unless there is a coordinated approach, what is being proposed is unlikely to have a big impact on any investments made so far in the country’s shipping industry.

The majority of shipping investments made in Myanmar since the country began its transition to a democracy in 2015 have been in the port sector, with investors mostly coming from elsewhere in Asia.

China has become the largest investor in Myanmar’s transportation sector, with a consortium of six companies led by the China International Trust and Investment Corp developing a huge container port in Kyaukpyu as part of the Belt and Road Initiative.

The project, which includes a special economic zone adjacent to the port and a 1,215 km (775 mile) rail link into China, is being billed as China’s back door into the Indian Ocean.

Other big investors include Hong Kong’s Hutchison Ports, India’s Adani Group, Japanese logistics conglomerate Kamigumi and Japan Overseas Infrastructure Investment Corp. All have invested in container and dry bulk terminals in ports close to the capital, Yangon.

Hutchison Ports and Adani have been approached for comment.

Calls for international action

Myanmar’s military junta has faced a strong backlash over the coup.

Condemnation was quick in coming, but so far there has been little sign of any coordinated international effort to sanction the country.

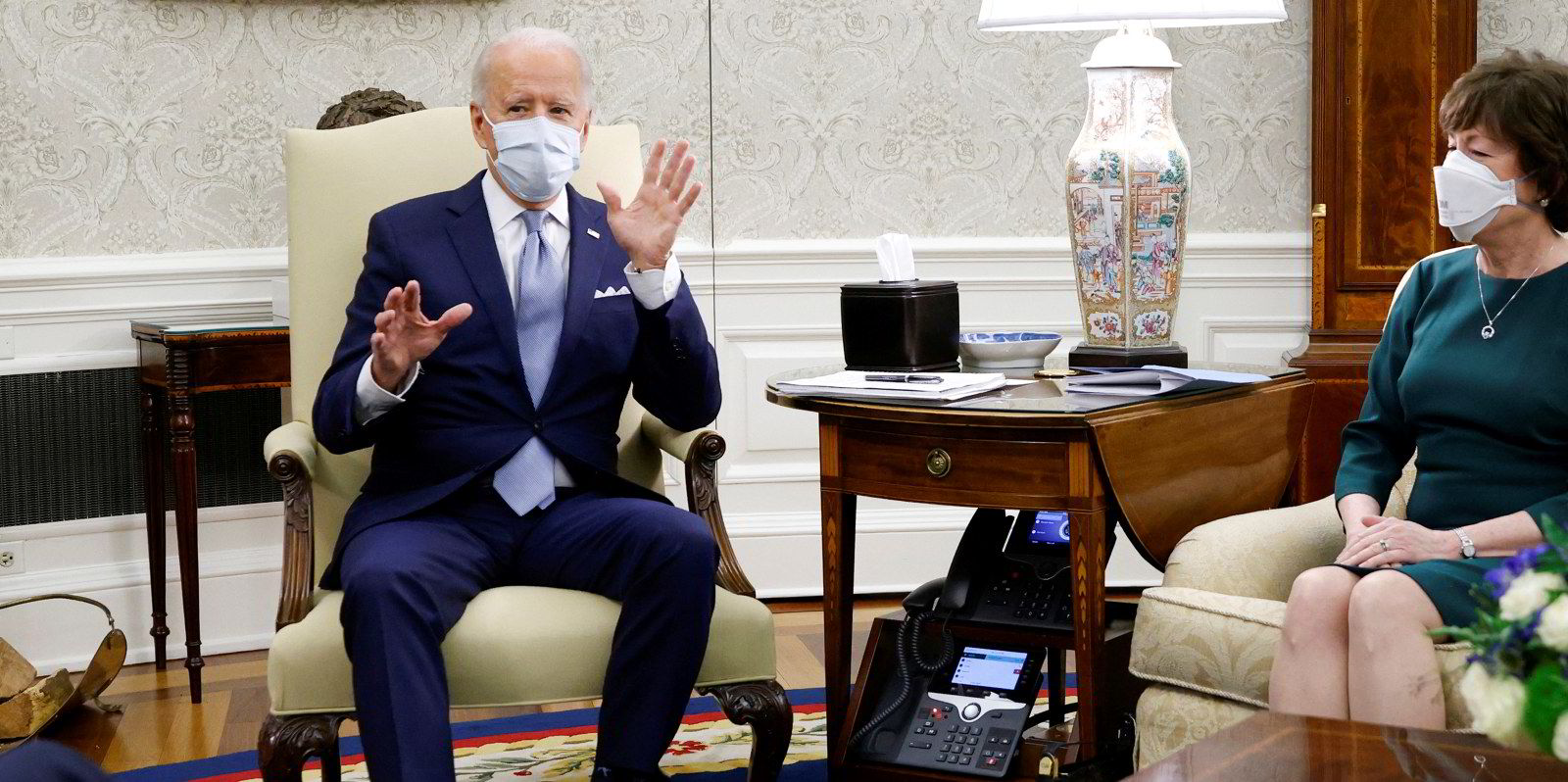

US President Joe Biden has led the call for a punitive international response, an effort that some commentators have described as the first big test of his pledge to collaborate more with allies on international challenges.

“The international community should come together in one voice to press the Burmese military to immediately relinquish the power they have seized, release the activists and officials they have detained,” Biden said in a statement shortly after the coup.

“The US removed sanctions on Burma over the past decade based on progress toward democracy. The reversal of that progress will necessitate an immediate review of our sanction laws and authorities, followed by appropriate action.”

The US has never recognised the military’s decision to change the country’s name from Burma to Myanmar in 1989.

Biden may be calling on other nations to join Washington in a coordinated sanctions effort, but so far there has been little sign of that happening.

While European leaders were quick to condemn the coup, analysts said any action by the European Parliament will take significantly longer because of the need for consultations among the 27 member countries.

EU diplomats told Politico that they were using “the typical diplomacy toolbox” on Myanmar, which meant starting with political appeals that could then advance to include further sanctions.

The United Nations Security Council has given no indication that it is prepared to take action despite the UN envoy for Myanmar, Christine Schraner Burgener, calling for an emergency meeting immediately after the coup.

Limited impact

The US and the EU have existing sanctions applied on Myanmar as a result of the Rohingya crisis of 2017, such as enhanced arms embargoes, the suspension of military cooperation, travel bans and asset freezes for members of the armed forces, including its leader, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing.

The wider economy has been left untouched despite strong involvement by the military.

Observers said it is unclear how much further the Americans and Europeans can go in terms of targeted sanctions without risking driving Myanmar’s military leadership under the wing of China, whose state media has largely dismissed the coup as nothing more than a cabinet reshuffle.

There is also a reluctance among Asian nations to impose sanctions.

Brunei, which chairs the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), which includes Myanmar, issued a statement on Monday noting that its principles include “the adherence to the principles of democracy, the rule of law and good governance, respect for and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms”.

The statement encouraged “the pursuance of dialogue, reconciliation and the return to normalcy in accordance with the will and interests of the people of Myanmar”, reflecting Asean’s default approach to resolving issues through diplomacy rather than confrontation.