A clearer picture is emerging of the demands that will be placed on shipping companies to reduce carbon emissions over the next two decades and more.

The IMO is discussing four main proposals ahead of a decisive meeting in April as it finalises plans for shipping to contribute to the Paris climate agreement. At that meeting, under the stewardship of secretary general Kitack Lim, one of the four targets is expected be selected.

All the proposals use 2008, the year shipping’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions peaked, as the baseline.

The most radical approach — tabled by the Marshall Islands, Kiribati and other Pacific islands that are already being severely affected by global warming — demands zero carbon emissions from shipping by 2035.

Then comes Belgium, which is calling for the industry to achieve a 90% improvement in ship efficiency and a 70% reduction in carbon emission volumes by 2050.

At the other end of the spectrum are the more modest goals of the International Chamber of Shipping, which wants to see emission levels kept below those in 2008, and a 50% improvement in ship efficiency by 2050. Although the chamber also wants full decarbonisation, it is looking to achieve that in the long term, but at least before 2100.

In an attempt to win a consensus at the IMO, and still meet Paris climate agreement targets, Japan has come up with a compromise that is gathering support among member states.

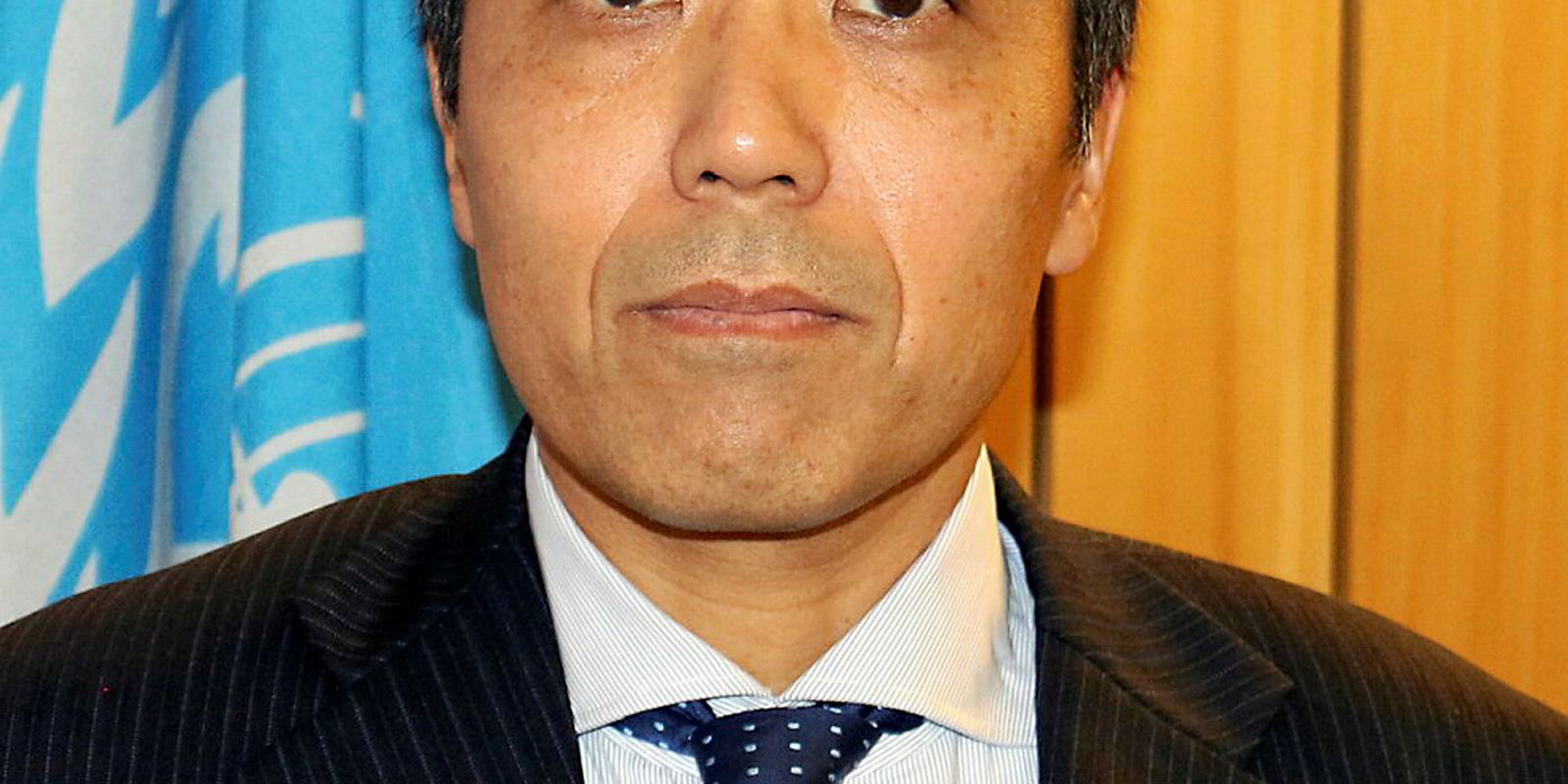

The IMO’s Marine Environment Protection Committee, which will discuss the targets in April, is chaired by Japanese civil servant Hideaki Saito, a factor that could help sway the committee towards Japan’s ideas.

The Japanese starting point is that the GHG goals must be “ambitious” enough to contribute to the Paris agreement of keeping the global temperature increase at less than 2C above pre-industrial levels, but also technically and commercially “achievable”.

The starting point, according to Japan, should also be to improve ships' fuel and operational efficiency. “Since transport volume in international shipping depends on global trade and is out of the control of the maritime sector, the sector can reduce GHG emissions only by improving efficiency,” it said.

Japan thinks a 40% efficiency improvement by 2030 is achievable. It estimates an 18% improvement in ship fuel and operating efficiency can be achieved through newbuildings and the IMO’s minimum standards laid out in the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI).

It is looking to introduce operational improvements, including speed reduction, retrofitting and maintenance, to gain a further 28% in efficiency improvement.

The Japanese also believe that the expected carbon cuts brought about by the 2030 efficiency improvements will buy time to develop alternative fuel technologies that could greatly accelerate decarbonisation.

They think alternative fuels could allow for a 50% reduction in carbon emission volumes by 2050. A further 40% improvement in ship efficiency could come from non-fuel-related developments.

“Although the reduction target should be efficiency-based in principle, a long-term target could be volume-based. A 90% efficiency improvement mostly depends on the readiness of alternative fuels and cannot be achieved by conventional approaches to improve shipping efficiency,” Japan said.

While admitting that alternative fuel technology is still shrouded in “uncertainty and challenges”, it believes the potential could be huge. “Overall carbon intensity will be reduced by 82% as a result of [a] possible fuel mix in 2060 consisting of LNG, hydrogen, biofuels and other possible alternative fuels,” said Japan.

Although the reduction target should be efficiency-based in principle, a long-term target could be volume-based. A 90% efficiency improvement mostly depends on the readiness of alternative fuels and cannot be achieved by conventional approaches to improve shipping efficiency

However, to meet the longer-term targets, Japan suggests alternative fuel technology will have to be in place by 2030, and the renewal of the world fleet with such technology will need to begin at that point.

Japan’s proposal would be in line with shipping making its “fair contribution” towards the Paris goals. The International Energy Agency estimates that a 50% reduction in shipping emissions by 2060 would be required to achieve the “Beyond Two Degree Scenario” spelt out in the agreement.

Highest possible ambitions

“Japan believes that the following targets are the highest possible ambitions that could only be achieved by the continuous effort by the sector, supported by the supply of alternative decarbonised fuels, and are consistent with the long-term temperature goal under the Paris agreement,” Japan said in its IMO submission.

However, critics point out that 2030 may be too early for shipping to turn to alternative fuels, particularly as until then there will be no mandatory instrument or commercial incentive encouraging the development of the required technology.

There is also doubt over whether the EEDI can perform in line with Japan’s expectations, given the current level of efficiency technology.