An Australian mining and energy company aims to fuel its ground-breaking ammonia-powered vessel for the first time in Singapore in February in the latest waypoint on shipping’s journey to become a zero-emission industry by 2050.

The 2,874-gt Green Pioneer (built 2010), a former offshore supply vessel, has been retrofitted by engineering experts from metals and energy company Fortescue, with two of its four diesel engines now able to run on ammonia.

The company, which is seeking to achieve carbon neutrality by 2030, said it was frustrated in its efforts by the slow development of ammonia engines.

It embarked on its own research programme using outside experts and in-house engineers with experience in complex mining operations to retrofit engines from the 1970s for use with ammonia after 18 months of work.

The age of the engines means that emissions reductions would be limited to about 60% of current levels. Newer technologies emerging on the market will bring that down closer to zero, said the company.

For now, the ship is being used as a demonstration project to show the possibilities of converting existing ships as ammonia remains off-limits for now as it awaits regulatory approval.

But the project has highlighted how the first steps to decarbonising the sector are achievable with available off-the-shelf technology.

The vessel sailed to Dubai from Singapore under conventional marine fuels for the COP28 summit. The US special presidential envoy for climate John Kerry and Arsenio Dominguez, the incoming International Maritime Organization’s chief, were among the visitors to the ship during the conference.

“At the moment, the regulatory landscape does not allow for ammonia ships to operate,” said Fortescue executive chairman Andrew Forrest. “Now it is up to the world’s ports to insist that their logistics do not harbour those who seek to hide from their responsibility to turn away from pollution.”

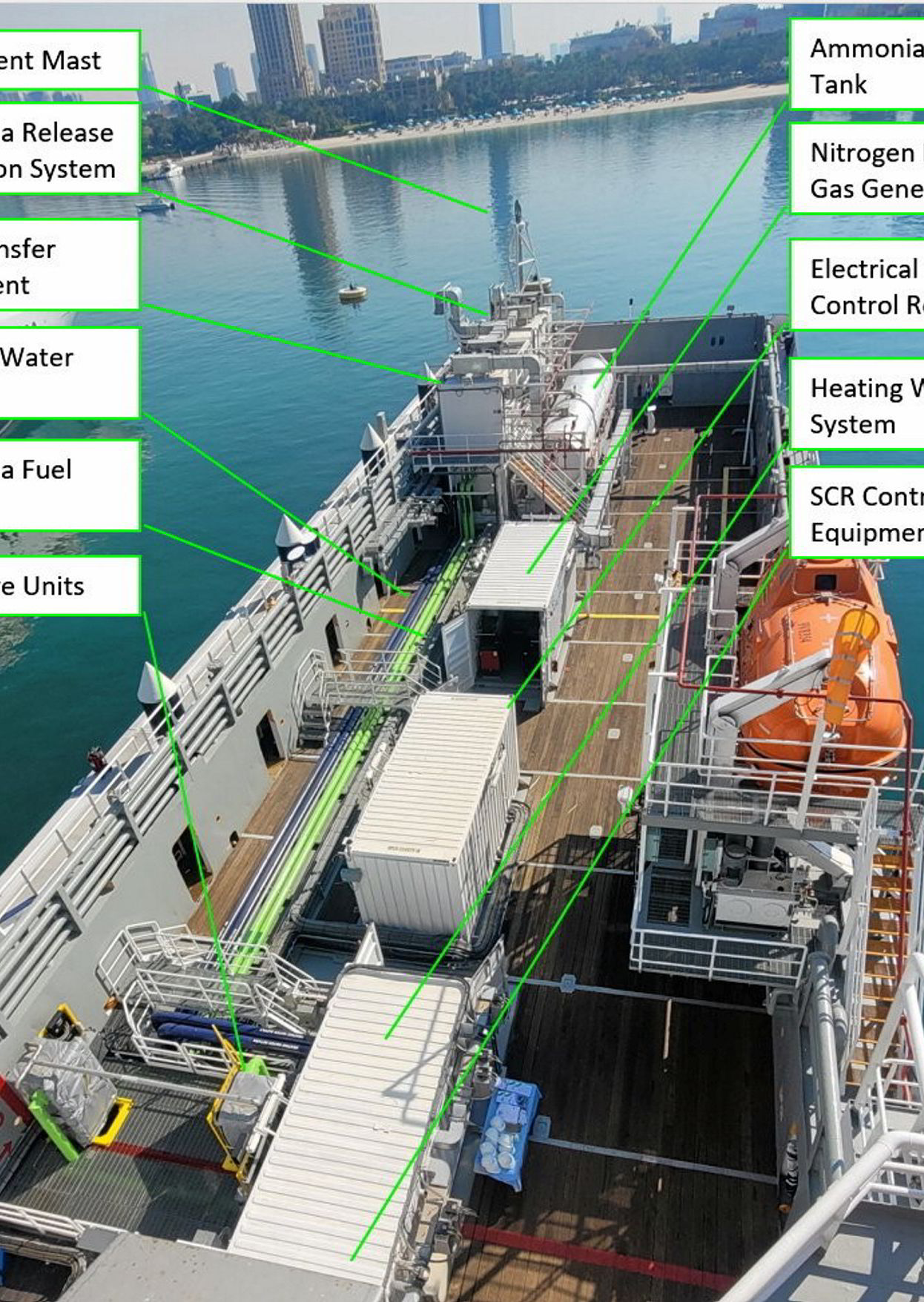

TradeWinds was given a tour of the vessel in Dubai Harbour Marina with members of the team behind the conversion for an insight into the future course of clean shipping.

Bunker Station

The pumping of ammonia onto the Green Pioneer has come under keen scrutiny from regulators as any leak of the highly toxic liquid has the potential to derail its use as a green fuel.

As part of the process on board the vessel, the human is being taken out of the equation. After the bunker hose from an onshore terminal is connected to the onboard bunker station, and safety checks are carried out, the crew heads to the bridge where they open and close valves using a remote touch panel.

Gauges and sensors monitor pressure, temperature and flow rates to check for any leaks. An electrical unit on the deck of the ship links the power systems and sensors through 30 km of onboard wiring.

For a ship the size of the Green Pioneer, filling the tank takes a couple of hours, with the liquid pumped into the tank at -33C. Before the pipes are connected, the pipework is then purged of any remaining ammonia.

Scrubber

The purging process involves flushing out the pipes with nitrogen. A citric acid solution reacts with the residue to neutralise the ammonia, turning it into a non-toxic byproduct that can be disposed of safely ashore. What emerges from the scrubber system via the vent mast is air with less than 30 parts per million of ammonia.

“You’ll smell it but if you put your nose up to it — I wouldn’t recommend it — you can breathe it and it’s perfectly safe,” said Mattison McGellin, the lead naval architect on the project.

Nitrogen Generation System

The systems on board the Green Pioneer have largely been built using off-the-shelf technology, said Andrew Hoare, head of shipping at Fortescue.

The purging system is based on two onboard generators that extract nitrogen from the air before it is compressed and stored in two tanks. The nitrogen is then sent via pipes to purge the ship’s networks of ammonia residues.

Ammonia Tank

The ammonia is pumped via the bunker station to the onboard ammonia tank, where the liquid rises to ambient temperature. The chance of the tank being ruptured is virtually impossible, said McGellin. “It’s literally bulletproof,” he said.

“In terms of risks … getting hit by a meteor, that’s the kind of likelihood that we’re talking about,” he said. “Even if we got pancaked against a pier by a 300,000-tonne bulk carrier laden with ore, the tank would not get crushed.”

If it did rupture, the plume from the release from the tank at the front of the ship is likely to go over the top of the bridge and the seafarers’ accommodation. There are safe refuge areas inside the accommodation with independent air supplies.

Fuel preparation room

The pressure created from the rising temperature of the ammonia in the tank allows it to flow into the adjacent fuel preparation room, controlled by valves.

The room is filled with connections, valves and instrumentation. As a precaution, the room has a double-door airlock system and is sealed off to seafarers while the ship is running on ammonia.

Residual heat from the engine’s cooling system is used to turn the liquid into a gas at temperatures of up to 40C before it is sent down the lines towards the engine, said Anthony Smith, the project and engineering manager for the Green Pioneer.

Pipework

The ammonia runs around the ship by pipes within pipes to provide an extra measure of security. Sensors within the pipework monitor for leaks.

Two green pipes carry the ammonia to a gas valve unit for the final preparations before it goes to the engine room.

Engine Control Room

The engines used on the Green Pioneer are a design that dates back to the 1970s, which limits the vessel’s ability to cut greenhouse gas emissions to about 60%. Diesel power will still be used to start the ship, although more modern designs will push it up to an emissions reduction of 90% or more.

An engineer on board the ship can monitor and control the flow of ammonia to the engines and shut it down in the event of any problems. The vessel is currently not permitted under regulations to run ammonia in port.

The coffee machine in the control room is hooked up to the ship’s power system. “We’ve been serving the world’s first coffee produced from a marine engine capable of being run on ammonia,” said Hoare. “It was a very good coffee.”

Engine Room

The engines have been converted to run on ammonia after an extensive testing programme at Hazelmere, Perth, in Western Australia.

They discovered that the corrosive nature of ammonia meant that some bearings and components used in traditional diesel engines could not be used, said Hoda Ehsani, a corrosions specialist. The first ammonia combustion was successfully achieved eight months ago.

The development of the engines was forced upon the company by events. The company, which is seeking to be carbon neutral by 2030, was looking to build an ammonia-powered ship but was told the engines would not be available for years — so they brought in a team to build them themselves.

Experts were brought in from Ferrari and Rolls-Royce to calibrate the engines. Two converted engines in the engine room now operate alongside two traditional engines.

“We want to bring the green molecule out to the world,” said Hoare. “We want to decarbonise our minds, decarbonise our operations and then become a major green energy company.”

Read more

- Shipping urged to do more on carbon capture as COP28 diverts from fossil fuels

- Comment: Shipping’s COP28 message puts it in the decarbonsation ballpark

- Seafarers bear brunt of failures to respond to Covid-19 crisis, says owner

- Singapore plans green corridor with China’s Tianjin Port

- The price just went up: Major flag state raises stakes in shipping levy battle