If there is one thing US authorities have been absolutely clear on their communications with shipping, it is their desire for vessels to have their AIS turned on just about all the time.

Two advisories from the country's Office of Foreign Assets Control (Ofac) in March 2019 warned companies that ships up to no good might disable the tracking system to hide their behaviour.

In May, Ofac joined the US Coast Guard and the State Department to publish more tailored guidance, instructing everyone from shipowners and crews to flag states to keep AIS on, lest they attract suspicion for sanctions non-compliance.

The only problem: The US wants to use a system vulnerable to all manner of manipulation to do something it was not designed for, potentially complicating its efforts to track global trade and creating compliance headaches for shipping.

"At the end of the day, AIS is the least secure protocol out there," said Omer Primor, head of marketing at Windward, an Israeli maritime analytics company.

"The amount of false positives is enormous."

What is AIS?

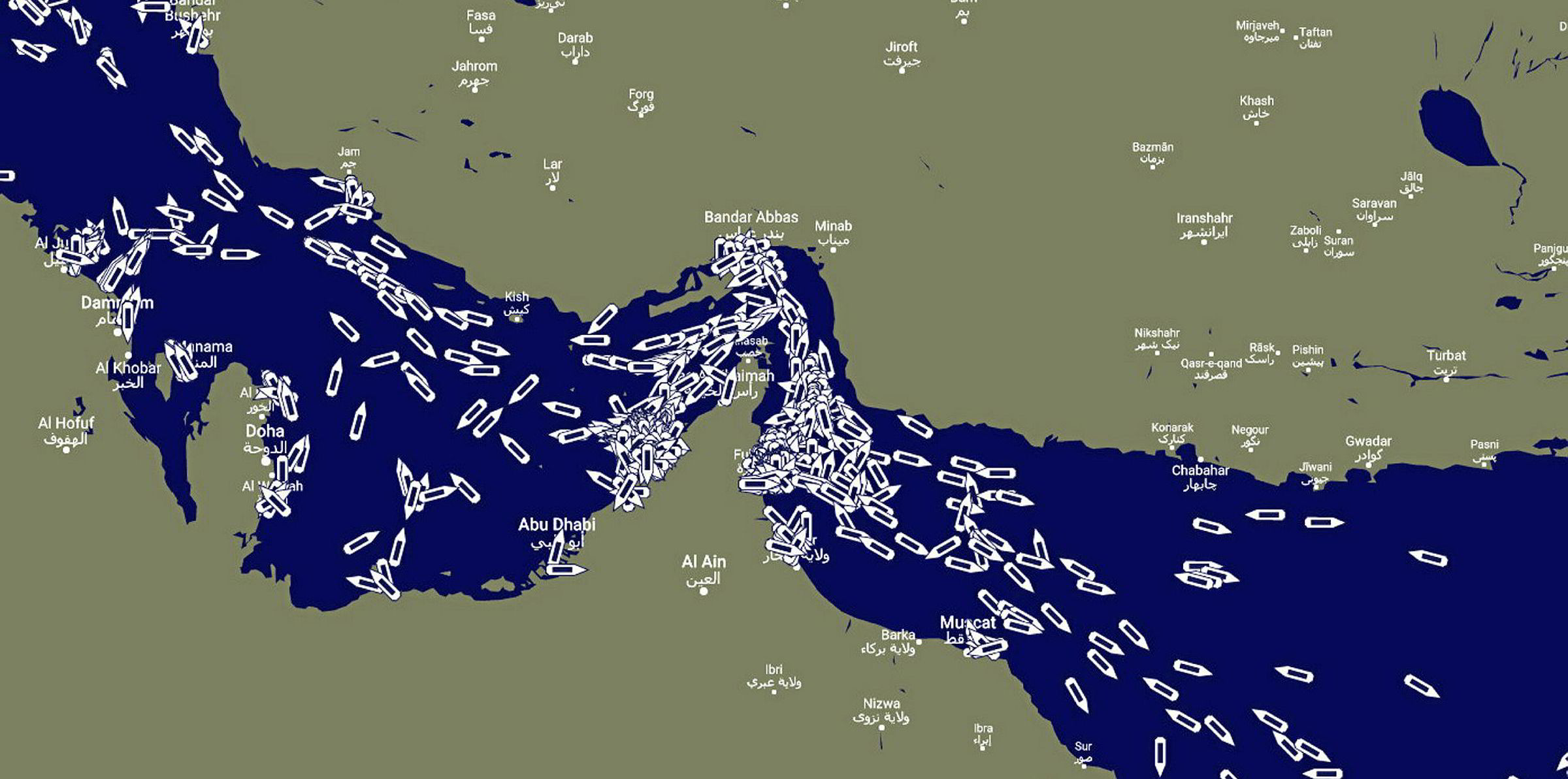

According to data from Windward provided to TradeWinds, there were a total of 776 VLCCs active worldwide in June.

Of those, 548 were lost at least once — meaning an eight-hour period where there was no AIS broadcast — and 78 went "dark", which Windward describes as a potentially deliberate "lost period in which speed, distance and coverage quality, among other parameters, indicate the ship could have conducted a significant activity".

The firm's analysis suggests just five of those dark ships exhibited behaviour consistent with sanctions-busting.

Mandated aboard all ships of 300 gt and larger by the International Maritime Organization in 2002, AIS was initially a means to prevent collisions.

With the technology — which broadcasts position based on GPS and other data crew input — seafarers would be able to more easily identify and contact other ships nearby.

Only when vessel tracking services became popular, did AIS become a means for the industry, commodities traders, authorities, NGOs and others to track their movement and goods worldwide.

With the US spending the last two years exerting more pressure on the industry as a means to enforce its sanctions regime, AIShas grown in importance as a compliance tool, with shipping fearful that doing business with an unscrupulous counterparty could land you on the US blacklist.

But gaps are easy to come by. Crews can simply turn it off while engaging in a ship-to-ship transfer of cargo destined for a global pariah, such as North Korea, or one of the US' geopolitical foes, such as, Iran.

Gaps can also be created when there are simply too many ships in an area, or by faulty equipment.

"The known limitations of AIS should be kept in mind when working and interpreting the information from AIS," said Jess Ford, senior research scientist at Australia's national science research lab, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation.

Ford was the primary author of a 2018 paper discussing a statistical model to determine whether a ship's AIS had been turned off or if the gap was created by other factors.

She sees both sides as an enforcement tool.

"If mandated, certain behaviours would potentially become more apparent and behaviour illegal and enforceable," Ford said in an email to TradeWinds.

"However, it might be challenging to take a safety system and convert it fully to a surveillance system. They have quite different characteristics. Moreover, it’s possible that using it for this purpose might undermine its original safety application."

'So 2019'

With the increased scrutiny, AIS manipulation has gone beyond simply turning the system off — a practice Primor described as "so 2019".

He said ships have set their AIS to transmit another ship's identity to evade suspicion. The innocent vessel would go about its business, while the impostor, now dark, would conduct its potentially illegal shipments.

Another method he suggested — which he admitted was an "extreme, theoretical case" — was using a transmitter and a computer program to create a fake ship that appeared on ship-tracking services to be moving, but did not exist in reality.

Primor and Ford expressed that more analysis was needed beyond simple AIS tracking.

The method Ford and her co-authors developed was one for ranking vessels based on the probability their AIS had been turned off.

The authors then deployed the model in the Arafura Sea between Australia, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea.

It ranked two vessels — a product tanker and a reefer — as highly likely to be engaged in questionable activity. The product tanker was potentially refuelling ships that were breaking the law and the reefer was transiting an area known for illegal activity.

Primor said Windward's use of artificial intelligence can help shipping companies separate common gaps from holes created by potentially nefarious activities.

The method flags questionable behaviour, saving industry players time, as Primor said companies are needlessly spending days vetting ships and companies, despite most AIS gaps being of the common variety.

"We're looking at a situation where ... the foundation will be, 'I don't trust you unless you prove otherwise,'" Primor said of the industry's future. "I think we're starting to see that."