Legitimate ship-to-ship (STS) oil transfers risk being caught up in a proposed crackdown on clandestine operations that seek to evade sanctions or high insurance costs, tanker owners have warned.

A group of nations wants stricter policing of STS rules to target a “dark” or “shadow fleet” of lightly regulated ships hauling sanctioned cargoes, but Intertanko, which represents independent tanker owners, warned that mainstream operators could also be affected.

It responded last week to a submission to the International Maritime Organization by a group of coastal states that sounded the alarm about pollution risks following a rise in transfers of Russian oil in European waters.

They called on states and flags to prevent “furtive” STS transfers within their coastal waters. They also warned that transfers on the high seas in areas with less maritime traffic would have fewer resources available to tackle a spill if the worst happened.

The group, which includes Spain, Australia, the US and Denmark, said some of the shadow fleet of 300 to 600 older tankers with substandard maintenance and unclear ownership have turned off satellite tracking systems to “circumvent sanctions and high insurance costs”.

But in its submission to the IMO, Intertanko said tankers are routinely advised to reduce the intensity of their AIS transmissions for operational and safety reasons during legitimate STS operations.

That could result in AIS signals not being picked up by a satellite orbiting 950 km overhead and in effect lead to the vessel “going dark”.

“So, the lack of receipt of a transmission cannot be taken as synonymous with illicit operations,” Intertanko told the IMO Marine Environment Protection Committee.

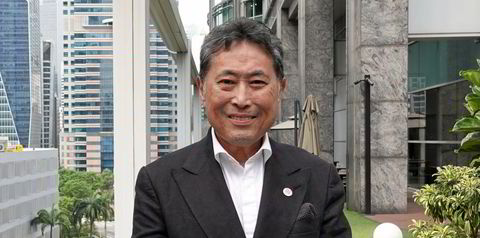

Dr Phillip Belcher, Intertanko’s marine director, who wrote the guidance, told TradeWinds that it is standard procedure to limit electronic emissions from radar, radio and AIS to less than one watt during STS operations from a normal operating level of about 25 watts. He said it could be done with a flick of the switch on the bridge.

“You can imagine: if you’ve got a one-watt light bulb in the middle of London, say, in your garden, and you’re trying to see that from 1,000 km in space, it’s difficult,” he said.

He added that this process is aimed at reducing “electronic interference in the systems which could cause problems”.

“Some people don’t, some people do,” he said. “It’s one of those things, but the guidance is there to do it.”

Belcher said the dangers are minimal but likened it to people being told not to use their mobile phones in petrol stations.

He also cited security concerns from the Gulf of Oman, where AIS signals have been used to target shipping. It has prompted some operators to switch off satellite tracking in the region to avoid being attacked.

Intertanko supports the intention of the crackdown but said a “few issues” need to be addressed so that countries can “differentiate between legitimate and illicit STS operations”.

Furtive operations

“Intertanko agrees there should be no ‘furtive’ STS operations,” Belcher told the meeting. “All operations should be undertaken in full view, and in compliance with multiple regulations and industry standards.”

Intertanko was backed by the International Chamber of Shipping, which represents shipowners. It urged members to ensure that legitimate operators are not unfairly penalised.

It said a distinction should be made between legitimate operations with AIS switched off for operational and security concerns, and “illegal operations being undertaken to circumvent sanctions”.

Some 11,500 STS transfers of clean and dirty oil products occur every year, according to major industry player SafeSTS.

They take place at 250 locations in 85 countries around the world, two-thirds of them in port.

The rise in transfers in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea is a result of changing trade flows from Russia because of Western sanctions and oil embargoes, but also an attempt to disguise the origins of the oil, according to the states urging stricter monitoring of STS rules.

The practice has allowed aframaxes loading at Russian ports to transfer their cargoes to VLCCs waiting off Greece, Spain and in the Atlantic to reduce transport costs for long-haul voyages to Asia.

But the explosion and fire on the 96,700-dwt Pablo (built 1997) in Malaysian waters in May has increased concerns that the “polluter pays” principle is at risk because of insufficient coverage if Western insurers have withdrawn from the market and owners cannot be identified.

The Pablo was deleted from three different registries in 16 months before the blast because it was involved in sanctioned Iranian trades. Its insurance position remains unclear.

Polluter pays

“This situation could leave coastal states with no party to hold liable and ultimately no recourse against the shipowner or an insurer, in the case of an oil pollution incident,” said the states’ submission, which is due to be debated at the IMO Assembly in November.

Under the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (Marpol), tanker operators should inform a state no less than 48 hours before a planned STS in its territorial waters or exclusive economic zone, which stretches 200 nautical miles (370 km) from the coast.

The paper calls on flag states to ensure tankers follow the measures that “lawfully prohibit or regulate STS transfers” to minimise the risk of pollution.