Research into robotics, particularly systems that drive autonomous vehicles, set one son of a Greek shipowning family on the road to developing vessel management software that would not disrupt the business but make it more efficient.

Ioannis Martinos, whose family runs Athens tanker management company Thenamaris, found it easier to solve physics problems at school than to learn Ancient Greek.

It led him to study mechanical aerospace engineering in the US, where a professor sent him off to a robotics competition.

Even though Martinos didn’t know anything about it, he was told: “Don’t worry, you will figure it out.” His team did, winning competitions two years running.

“I was really passionate about it,” he tells TW+. The team got good at building mobile ground-based robots — similar technology to that now used in autonomous cars — so it moved on to flying robots.

“It turned out to be easier to build a flying robot than a ground robot,” he says. “Autonomous cars don’t exist yet fully in our day-to-day lives, but drones have for a few years now. To make it a bit more interesting, we worked on autonomous helicopters — which still don’t exist.”

That project at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) “made me understand you can do a lot more with your brain if you really push yourself hard, and MIT was great at pushing you hard”.

A pattern of setting a goal and then finding a way to make it happen developed that he has continued into a shipping career over the past decade.

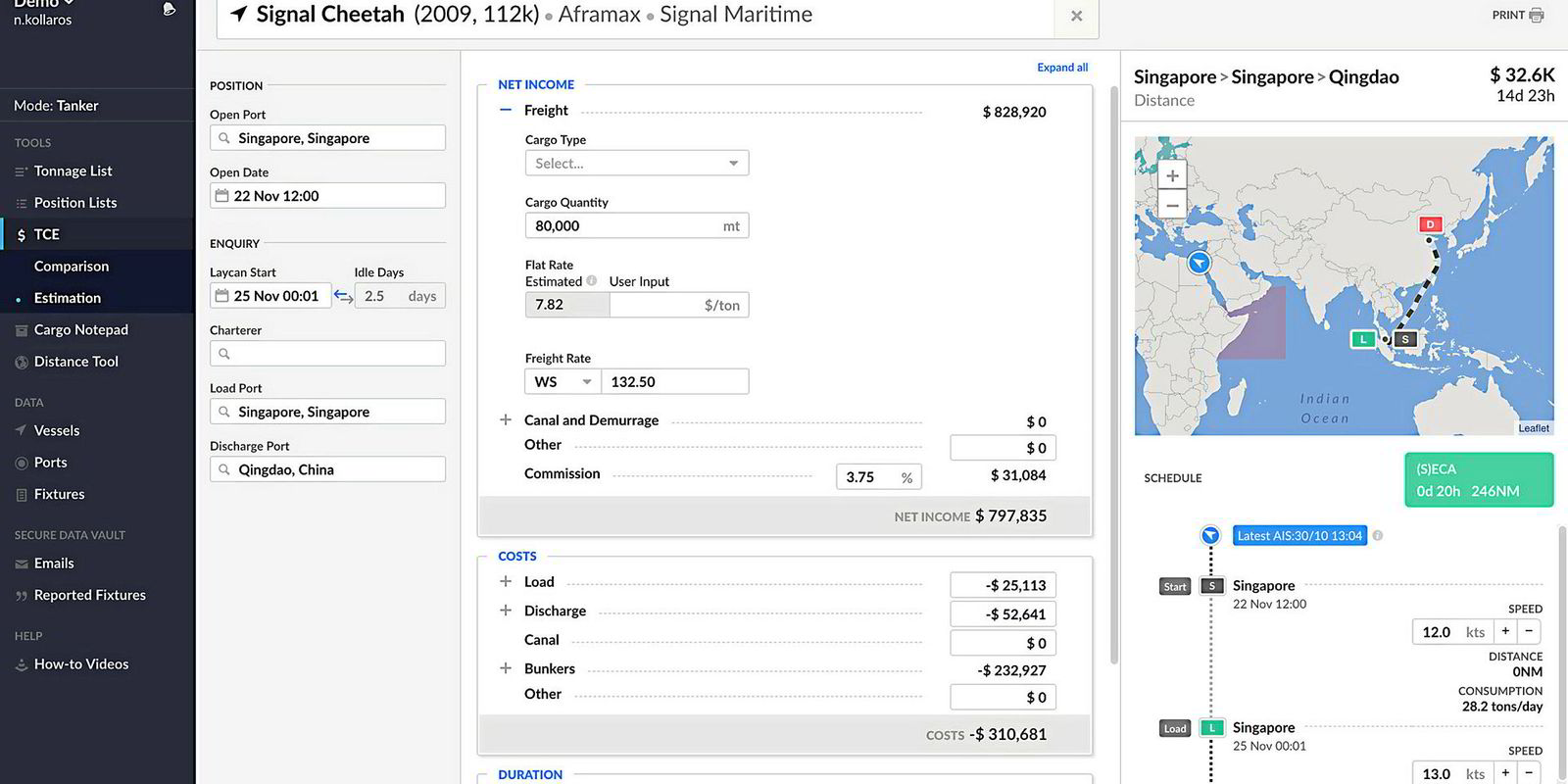

“When the time came for me to do my own thing, I chose one of the most difficult problems I had seen in shipping: how do you have the most accurate information for daily commercial decision-making?”

Martinos had been a joint chief executive of Thenamaris, but now set up a separate company, Signal Maritime, with the aim of taking the art, or perhaps science, of shipmanagement to the next level.

“It turned out the problem was even harder than we had thought — and we already had a pretty good idea of how hard it was going to be.”

The software that is now being marketed for sale by subsidiary Signal Ocean was originally developed for Signal Maritime. It has taken four years to develop.

Martinos says that, unlike many technology start-ups that launch systems before they are fully ready, in order to learn from feedback, Signal Ocean’s platform has undergone its testing in-house because he felt shipping companies had to be able to trust it if they were to base expensive decisions on it.

“The best way to test that was to eat the food we were producing ourselves.”

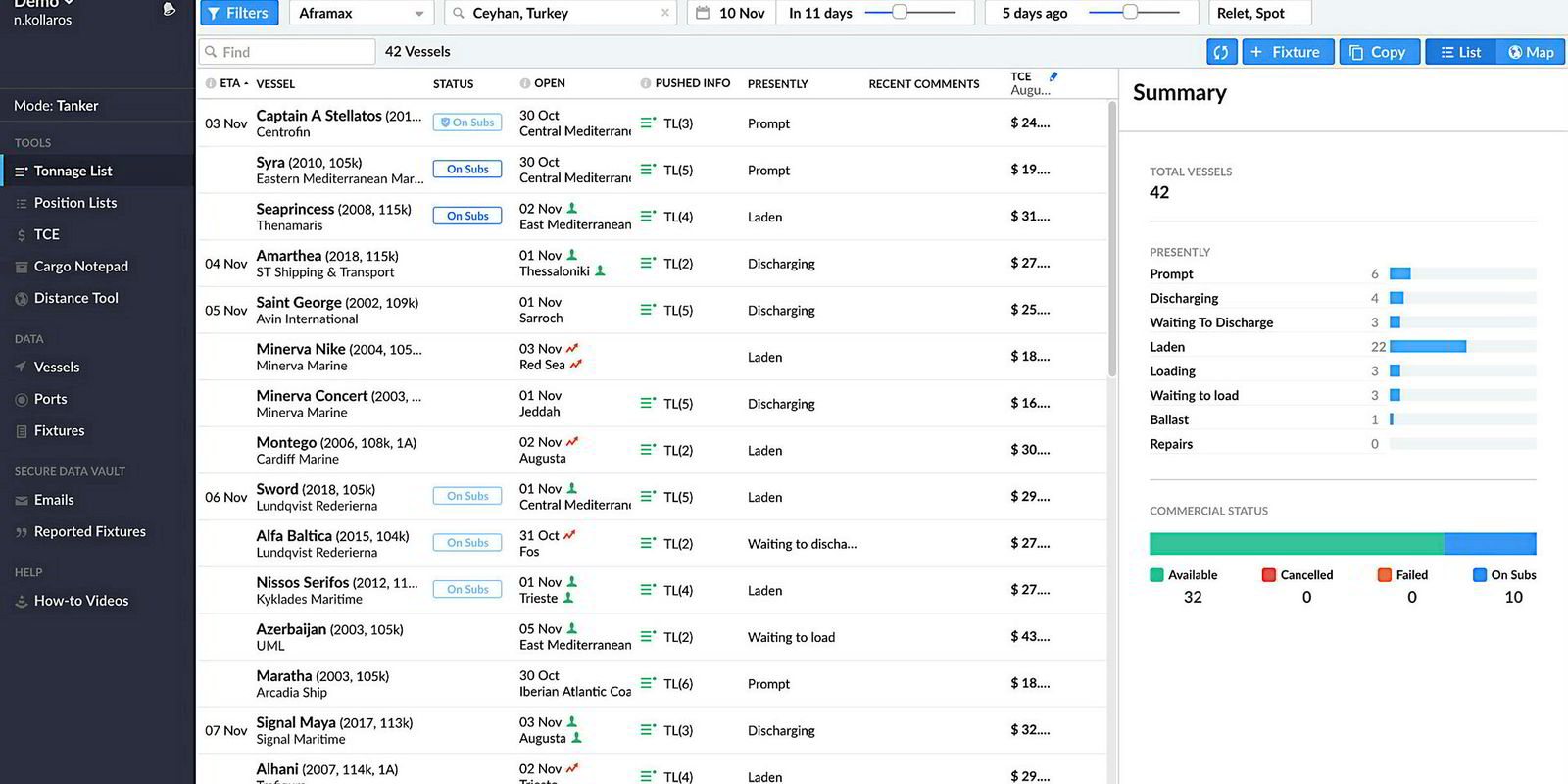

Over the past two years, he claims, the system has helped Signal Maritime achieve one of the best market performances in terms of spot utilisation of aframax tankers. And what it needed as a commercial ship operator also turned out to be what charterers need.

Crucially, the Signal group chief executive stresses: “We are not trying to disrupt shipping in the same way Uber tried to disrupt the taxi business. From the beginning we said we would respect the market structure.”

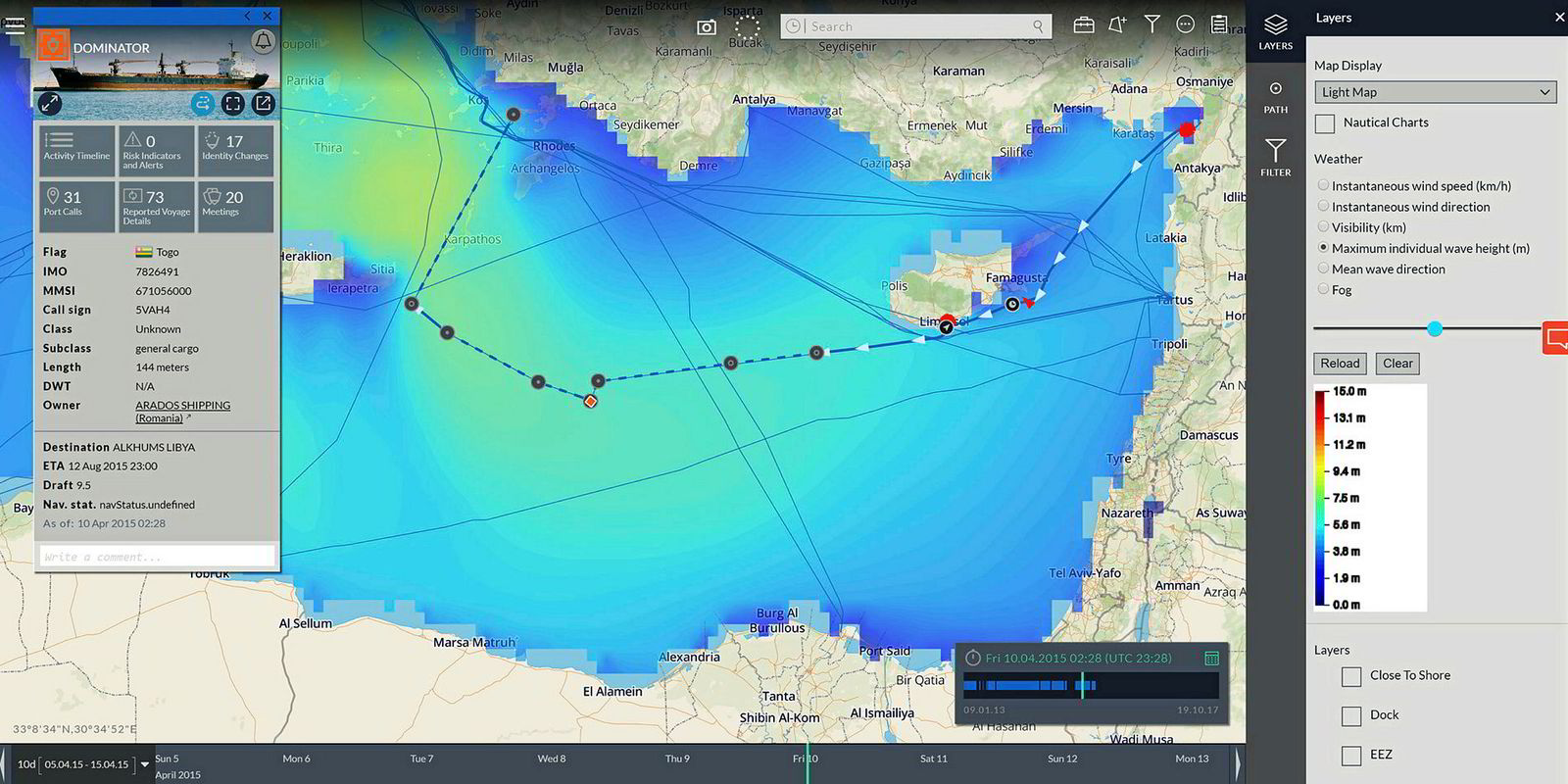

Signal Ocean’s platform extracts information from fixture reports and tonnage-list emails and combines it with publicly available data to provide a single commercial view of the aframax, suezmax and VLCC markets.

It is already used by operators responsible for half of big tanker spot fixtures, according to Martinos.

The system does not provide market information, but is like an engine: users put in their own data as the fuel to provide them with a singular view of the world on which to base decisions..

We’re not trying to disrupt shipping in the way Uber tried to disrupt the taxi business

Martinos describes the way it works as a “marriage of man and machine” in which the computer provides the speed and efficiency of data integration. “Everything we do could be replicated manually — it would just take a very long time.”

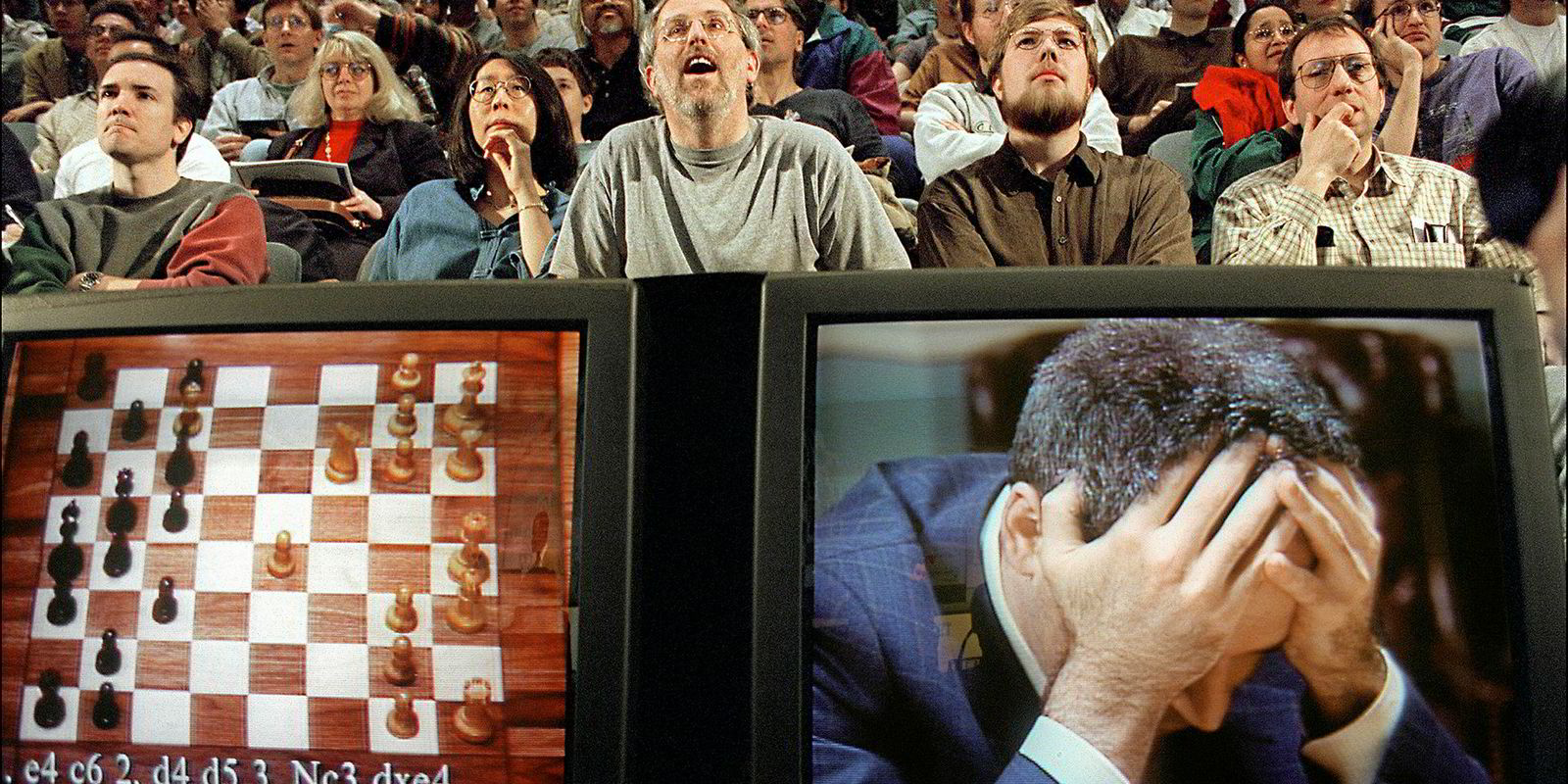

He cites chess master Garry Kasparov. Since he lost to the IBM Deep Blue computer in 1997, the best chess programs have always been able to beat humans.

But Kasparov organised a championship in which a mixed human/computer team working in unison won against solely human or computer contestants, even though it did not necessarily have the best players or technology.

Martinos is pleased by the positive reception Signal Ocean has received from shipping companies, but is working to make it better.

The other aim for the next year is to go back to his core shipmanagement business and use the system to develop the most efficient vessel pools.

“Technology is a subscription business model. It is interesting, but not very interesting. If you want to sell the concept of marrying the machine and human for commercial decision-making, an effective way of doing that is through pools.

“If a pool is very good at utilising the technology with the shipping experience, it can have really good performance and become one of the best pools in the industry. That’s our next step, what we want to focus on over the next year.”

Signal Maritime launched an aframax pool in September to test the theory and will start marketing it more actively from January. Later it aims to develop pools for suezmax tankers and VLCCs.

“If people could use the technology perfectly, at 100% utilisation from day one,” he adds, “then you could ask for a very big subscription because they would recognise the value. But that is unrealistic.

“We waited for the product to be useful from day one, but it is not ‘feature complete’. So we need to complete the features.”

The system’s ability to read unstructured data is close to 70% of whatever is thrown at it, but the target is to get to 98% over the next year and ensure it is able to use all the input fully. Currently, working sequentially, computers cannot see all the connections a human could, but that process can be built into the algorithms.

It is like developing an autonomous car for which changing road conditions need to be considered and evaluated instantly.

“It is easier to develop for Singapore, where everyone obeys the law, than it is for the streets in Athens, where the driving is a bit more hectic.”

This is also true of expanding the Signal Ocean platform to handle the more complex trading patterns of smaller tankers. It does not yet cover clean aframax, panamax and MR tankers or dirty panamaxes.

A dry cargo system is also under development, and in the long run Martinos can see Signal Maritime going into the dry bulk sector on the back of it. It is not the priority, though.

“It’s important not to try to do too many things at once. Now the focus is on tankers. We want to get into the game in dry, but longer-term.”

Other software developers are looking into building similar systems, but Martinos believes Signal Ocean has a lead because it has been working at it longer. “I don’t know of any other company that has managed to have a viable tonnage list from automated sources. That’s the threshold.”

Signal Ocean is also on the verge of launching a special module for brokers. Again, it is crucial that the system does not challenge the business but helps it.

“It is reasonable to assume that technology is coming, so brokers would rather have this technology coming to the market than another that does not respect the market structure. People would rather it comes in the right form, and we represent that.”

Although some brokers might fear giving away their information to charterers and owners, Martinos says the three sides of the business will be able to have more intelligent and ultimately profitable discussions about the market.

“Instead of asking what is out there, you could discuss the ships that matter to the market you are acting in. In my opinion it helps protect the relationship with the broker because you are not asking them to do magic on your behalf. I think it has actually strengthened our [Signal Maritime’s] relationship with our brokers.”

The main extra element needed for a broker's version is an ability to reconcile and check information, to make sure everything lines up, Martinos says. “In pilot testing, brokers said it had this shortcoming.”

The sequential nature of a computer means it cannot cross-check facts like a human, keeping in mind all the information to make and change decisions. The complexity of the algorithms has to be developed.

And yet again we are back with autonomous vehicles. “When an autonomous car comes to a crossroad and sees a car in another lane and a pedestrian waiting to cross, it needs to recompute everything if a jogger suddenly runs in from the other side — it cannot just add it to the information.

“Everyone wants better information than everyone else,” Martinos sums up, “and that is what we focus on. We are not democratising information; we do not believe in that. It is about utilising to the maximum what you have, and gaining a bit of an edge.”