Taking a window seat on a flight from Europe to Shanghai is to have a front-row view of the spectacular economic development that has shaped China and driven the global shipping industry over the past 30 years.

As the arid plains of central Asia morph into China’s western mountains, far below, coal mines, power stations and wind turbines start to appear, all linked by roads bulldozed though the roughly corrugated landscape.

From 36,000ft, the hills of northwest China slowly decay to the lowlands and flood plains of Henan province. A landscape littered with new towns and factories is revealed, with its web of roads, railways and pipelines.

Then on the descent into Shanghai’s Pudong airport, the sea of industry, transport and housing in today’s workshop of the world around the mouth of the Yangtze River comes into close-up. Shipyards, motorways, industrial units of every shape and size, and a sea of apartment blocks seemingly thrown up in super-sized Lego.

And as the plane banks for its final approach, the crowded shipping activity in the mouth of the river swings into view. Oceangoing bulkers, boxships and the occasional LNG carrier are interspersed with a teeming array of small sea-river craft laden to the gunwales with cargo.

These scenes are a product of three decades of unprecedented economic growth, sparked by former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping under the banner of “socialism with Chinese characteristics”.

Without the boom initiated by Deng, global shipping would be a very different business today.

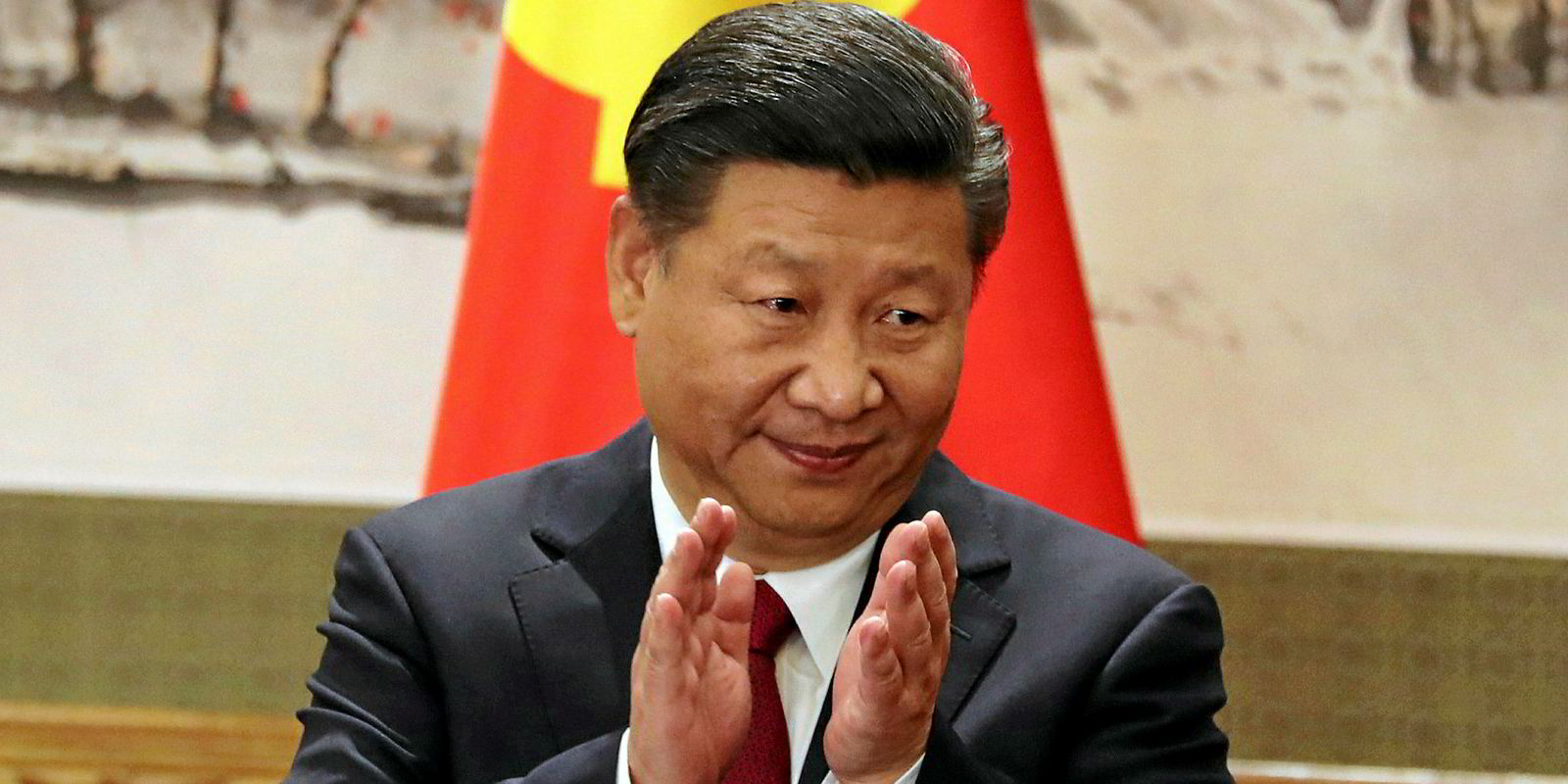

Now China’s latest strong-man leader, Xi Jinping, is seeking to assert his country’s place at the head of a new world order by extending its economic power overseas through the Belt and Road Initiative.

It has implications for freight, shipbuilding, ship finance, regulation and even the freedom of navigation as China attempts to take a dominant strategic role in the South China Sea and other parts of South and East Asia.

Belt and Road is starting to provoke rare excitement in the global shipping industry. Hopes rest on the possibility the project could stimulate huge volumes of added trade to fill ships, as well as supply much-needed capital for shipowners through the expansion of Chinese finance.

But deep-rooted fears remain over whether a new trade boom will be realised, due to concerns about whether Beijing can continue to manage the country’s vast debt bubble.

While some observers are optimistic in the short term, others remain sceptical about China’s ability to deliver on Xi’s grandiose scheme, which only emerged rather haphazardly over the past three years.

And hovering over everything remains the issue of China’s government becoming more autocratic and illiberal and increasingly hostile to private business.

“In the short term the Belt and Road project will help the shipping industry,” says Mark Young, chief executive of Asia Maritime Pacific, a handysize bulker company based in Hong Kong. “In the past 10 years we have seen volumes between China and Africa grow sharply. In the long term it is hard to say,” he cautions. “It may create the volume, but I am not sure if they are healthy volumes.

“I think for the long term of the Belt and Road we still have to look into the details of those projects, to see if they can be built, can be run and can be managed efficiently. I think this is still at an early stage to come up with a conclusion.”

Speaking alongside Young at the Tradewinds Shipping China conference in Shanghai in October was Yang Lei, head of ocean transport, China and Asia-Pacific, for global commodities group Cargill.

“Our group has an extremely positive view of the Belt and Road, as Cargill is always a defender of globalisation and free trade. Personally, I think the Belt and Road Initiative will benefit the whole world,” Yang says. “It will develop global trade.”

He is one of many who draw parallels with the Marshall Plan of US aid to help rebuild Europe after World War II. At the time, the $13bn scheme was the biggest infrastructure investment ever made, equal to $130bn at today’s value.

But that is dwarfed by the notional $900bn value put on Xi’s Belt and Road project. And as Yang admits, parallels are clear between the influence-building impact for the US of the Marshall Plan and Beijing’s power play with Belt and Road.

“I am a Chinese living in Singapore, and I think that Belt and Road is for China to export extra capacity, extra capital and our geopolitical influence. I am just trying to be honest. I remember that America did it years ago, and Japan did the same. It is pretty simple.”

Heightened interest from the shipping business in the potential for Belt and Road projects comes after a period of intense scrutiny of China’s next moves. Not only has the country this year again managed to avoid the debt crunch many outside observers believe is inevitable at some point, President Xi has reinforced his hold on power.

In securing a second five-year term as Communist Party secretary-general at October’s 19th party congress, he cemented his position as the country’s most powerful politician since revolutionary leader Mao Zedong.

Approval by delegates of the historic inclusion in the party constitution of “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” was merely a political embellishment of the 64-year-old’s control, which some believe will see him remain in post not just until 2022 but for another five years to 2027.

While much has been made of Xi’s clampdown on corruption, less attention has been focused on the impact of his ideology on companies, suppression of political dissent and a failure to follow through on promises of reform.

Much of his approach appears to reflect desperation to avoid what happened in the former Soviet Union, where the old Leninist elite rapidly lost their grip on power as dissent flourished.

Most analysts agree Beijing will continue to cut back excess ageing capacity in the steel, coal and shipbuilding sectors, and step up international engagement through initiatives such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. The regime has compromised by maintaining employment levels and kept the housing market bubbling to avoid social discontent.

British economist George Magnus wrote last month: “Some things, important to economic development, seem very unlikely to change. These include the conflicted role of the party-state as owner, participant and regulator [and] the absence of the rule of law and a comprehensive system of land and intellectual property rights and registration.

“The prominent political role of state enterprises is being strengthened, and the concentration of wealth and assets in the public sector is rising.”

Despite such concerns, the scale of China’s economy and the opportunities presented by even modest growth remain so large, it is hard to comprehend.

Since 2010, when Chinese economic growth started to slow, nominal GDP has still doubled from $6trn to $12trn. And even though growth last year at 6.8% was the lowest for a quarter of a century, it was still the equivalent of creating another Australia, or half a UK.

Already two-thirds the size of the US economy, China remains on track to become the world’s largest economy in 2027 or 2028. Its trading power is growing rapidly. It is now Germany’s largest trading partner, having overtaken France and the US.

Lord Jim O’Neill, the former Goldman Sachs economist who in 2001 coined the term BRIC for the high-growth quartet of Brazil, Russia, India and China, put it bluntly in a BBC interview.

“Anything to do with the economic context of China, very quickly Westerners lose their objectivity. It defaults to: ‘I don’t believe it! They are a bunch of Commies! It can’t be true!’”

In particular, he highlights the growth of Chinese consumer spending this decade to $2.5trn — equivalent to the whole of the Indian economy. “The Chinese consumer is easily the most important thing in the world economy, and for every company and country,” he adds.

Rapid expansion of China’s ship finance sector over the past five years has been fuelled partly by the country’s huge trade surplus, which reached $530bn in 2016 and created a sector desperate for suitable clients and projects.

However, even those at the heart of the business caution that the expansion is more modest than it may appear to outsiders.

Gao Zefeng, vice general manager, transport finance, at China EximBank, says that while Chinese ship finance has grown since the global financial crisis, it remains substantially smaller than the contribution of European banks.

Gao told the TradeWinds conference that China accounted for only about 3% of the world’s $600bn ship finance portfolio in 2008. While the total fell to around $400bn at the end of 2016, China now accounts for about $60bn, or 15%-20%, he says.

James Tong, Citi’s Asia-Pacific head of shipping and logistics, echoes the caution, although he welcomes the emergence of the new breed of financial leasing houses.

“I think it’s very good to have new entrants to the market, especially the Chinese financial leasing firms, as they have good financial performance and strong balance sheets,” he says.

However, the statistics can be misleading. “If you look at the volume, it is far less than what the German banks have done over the last few years. It is just there are more of [the Chinese firms] and they are more active.

“People see that the vault is open to come and get the money, but it is just not true. Chinese lessors are very selective about how they invest their money too. The reason they are coming to the international market is they needed to diversify their portfolio.”

There are now five Chinese lessors among the 30 biggest lenders to the industry, but they remain comparatively small, according to Zhao Shen, head of credit, risk and legal management at CSIC Leasing.

“In terms of the overall portfolio of the Chinese leasing sector, shipping is still very small. But in terms of new money, in 2016 the Chinese leasing companies were very active and the momentum is great,” he says. “I think they will play a very important role in the international shipping market, but not the leading role.”

The influence of central and regional government in directing lessors’ strategy and choice of projects remains a powerful force, according to those involved. Pressure has been placed on financiers to avoid newbuilding projects at overseas shipyards, and to back Chinese-built projects.

Fang Xiuzhi, head of shipping at Bank of Communications Financial Leasing (Bocom), admits it has become a sensitive issue since one Shanghai lessor came under pressure after backing a foreign newbuilding project.

“Banks and shipyards are always in a competitive environment,” he says. “And because it is a competitive environment I can understand why there are some complaints.

“If we can do something for shipyards when we are doing business, we are happy to. Some leasing companies are under pressure, but as a leasing company doing international business, we are mainly focused on the requirements of our clients.”

Although major shipowners remain able to access finance despite the retreat of many lenders from the international market, smaller companies are struggling.

Tong says: “It has created two tiers. Shipping companies and smaller, individual shipowners may find it is not that easy to get money. Most of the middle companies might have to merge.”

Chinese lessors have until now focused on major clients, although some are examining whether there is scope to move into providing finance for smaller owners.

“Our next big challenge will be to do business with middle-size or even small-size clients,” Fang says. “We need to focus on the key competitive factors of those clients, not just according to the names or size or charterparties. We need to improve our risk-control abilities.”

Finance from Chinese lessors for smaller international owners will develop only if there is greater openness of trade and business practices, cautions one major shipowner.

“The one caveat [to the growth story] is that I hope China does not make trading more complicated for foreign-flag ships,” says the regional head of a group who declined to be identified.

“If they decide that a certain proportion — or a large proportion — of the imports and exports must go with the Chinese flag, then this is not such a happy situation.

“We as a company invest a lot in China. We build ships in China, we employ Chinese crew and we repair our ships in China. We contribute to the Chinese economy. But if as an international shipping company we are restricted from certain trades, then that would be a negative.”

Yang plays down such fears. “Is it a threat? I don’t think so. Chinese-flag ships only have the advantage in the coastal trades.”

It is a view reflected in the modest growth rate of the Chinese-owned oceangoing fleet in recent years. It has been far slower than trade growth, and lower than many industry analysts forecast.

Clarksons Platou Asia managing director Wang Chengyu sees the China story remaining positive, despite potential pitfalls.

“I think it is very positive for global trade. In micro terms we have already seen the recent study that the Asean countries, such as Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia, are going to increase their coal imports by up to 10 million tonnes a year.

“And in the longer term it will benefit world trade. Chinese money going out will in its turn create wealth and demand for Chinese goods.”

Belt and Road may trigger the development of new trades, says the Baltic Exchange’s chief commercial officer, Janet Sykes. “We have been asked to look at other types of indices that might support the Belt and Road Initiative. Maybe there will be some new intra-Asian trades developing. We are at the start of a very long discussion.”

A distinction of Belt and Road is that it is an investment plan, unlike the aid-driven nature of the Marshall Plan. China needs to finance the infrastructure and it is estimated that only a fraction of the potential $900bn has been secured so far, perhaps as little as $2bn.

And for that financing to be repaid, the projects need to be financially credible and efficiently managed. And there lies the risk, according to the shipowner.

“The Chinese footprint on the world is really like some kind of colonisation. I think China hopes the investment it is making in developing these other nations and cities will eventually come back to it,” he says.

Wang is more sanguine. “By making all these investments China will create demand for Chinese goods. Asians have a theory that for a country to be rich, you need great demand for your products. I think it is a strategic investment.”

But an example of how strategic investment can go wrong can be seen at Hambantota port on the south coast of Sri Lanka. Built earlier this decade at a cost of $1.3bn with Chinese finance, it has failed to win business and sits largely idle.

In July, China agreed to a $1.1bn debt write-off in exchange for the facility being handed to Beijing-controlled trading giant China Merchants, causing furious criticism of Sri Lanka’s government for selling national assets.

Yang believes China’s Belt and Road infrastructure investments will be key for the whole shipping chain over the next decade.

“We have a very interesting saying,” he adds. “‘If you want to be rich, you need to build your roof first’. That emphasises the importance of infrastructure.

“The whole world has benefited from Chinese industrialisation over the last 39 years. Now we are looking at the ‘next’ China. Chinese investment is building roads, rail and port infrastructure. It’s that infrastructure that’s important.”

For Belt and Road to succeed and shipping to take a share of the trade growth created, business leaders and analysts believe that real reforms of Chinese state-owned businesses are needed.

Xi’s first five years have left overseas companies operating in China with “promise fatigue”, the EU Chamber of Commerce in China says. Many will be watching to see whether those promises will finally turn into action, or whether the need to control political dissent binds China to an increasingly centralised and authoritarian future.