When shipbroker Charles Barne was clearing out his father’s house in 2012 he made an unexpected discovery.

A cache of diaries written by his grandfather, Anthony Barne, chronicled the six years of World War II, his daily experiences and personal encounters with British wartime prime minister Winston Churchill.

Fast-forward seven years and the younger Barne, who works for Greek owner Lykiardopulo in London, is awaiting delivery of the first copies of Churchill’s Colonel: The War Diaries of Lieutenant Colonel Anthony Barne. The book is the result of three years’ work during his long daily train commute.

It is being published by Pen & Sword in early October, with all proceeds going to the British charity Walking With The Wounded, which helps military veterans re-integrate into society and find employment.

Charles Barne grew up living alongside his grandparents. His parents shared a market garden plot with them in Dorset on the southern coast of England.

Although he was unaware of the diaries, he regularly heard his grandfather talk about the war and knew he had a connection with Churchill.

Both his grandparents died when Charles was 18 and away on a gap year in New Zealand. He was very affected by their deaths and “sad that window to another world had closed”.

But it was to reopen again after the death of his own father when he found the A5 diaries, one for each year of the war, neatly inked in his grandfather’s hand on yellowing paper — “exactly as you would want them to look”, Charles says.

The pages give a fascinating insight into the life of a young man who, like so many of his contemporaries, was caught up in the chaos of war and catapulted into countries and situations far from home and what he might have expected for his life.

Anthony Barne expressed forethought as he started to write them, recording the words: “This Diary was started shortly after leaving England to return to Palestine as it was thought that the period between departure from Palestine and an unknown date in the future might be of interest many years hence.”

The diaries open on Saturday 19 August 1939, when Barne, not long married, is starting a period of “longed for leave” from British Mandatory Palestine, where he has been posted with the Royal Dragoons. But he has been back in Britain for only four days when he is summoned back by his regiment.

Barne is on a troop ship heading for Spain when war is declared. A week later, as his vessel docks in Malta, he writes: “I fear this will become a world war again and could last several years.”

His fears were realised. He spends the next six years writing a page each day detailing his life, with all its frustrations and fears, but not without considerable fun, often sought in the most surprising of places.

Years later, his grandson has worked hard to edit the entries down so they provide an insight into the war years while preserving a true picture of his grandfather.

There are ships aplenty in the book too. Early in the war, Barne is put in charge of running the Palestine port of Haifa, supervising cargo and troop movements. He is also sent to Tobruk in Libya, just after it is liberated, and is tasked with bringing the port back into working order.

Turning ships round quickly has Barne and his men working long hours but clearly with a keen eye on the cargo.

On 15 April 1940 he writes: “A big Norwegian ship has come in empty and is immediately detained. Lesbos is hard at work discharging timber and some corrugated iron. Hatsu doesn’t quite finish and in the morning drops eight cases of bacon overboard. The bacon is £5 per case and we think it’s worthwhile to use a diver to recover.”

But the progress of the war is ever present. On 10 May he records: “Everyone stirred by the wireless announcement that Hitler has invaded Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg. It must be the last throw of a madman. Like Samson he intends to die and cause as much havoc as he can in the collapse.”

Life is not all bad, though. There is an account of skiing in Lebanon in 1940, a trip to see the Pyramids and the Sphinx for his wife Cara, who came out to live with him, and numerous parties where a deal of alcohol is consumed despite the deprivations of war.

By 1943 he writes: “I’ve started a new drink to safeguard the whisky. We have gin with a couple of drops of Worcester sauce. It’s really quite palatable.”

His son Christopher (Charles Barne’s father) is born in Cairo on 12 May 1941. “He’s a magnificent little chap, 6¼ lbs but fat as butter and with a lovely complexion,” Barne writes. The following day he adds: “The brat is very well behaved, is a good feeder and makes little noise,” before moving on to record the strange reports of Hitler’s deputy Rudolf Hess and his lone flight to Scotland.

After some colourful twists of fate, Barne is made second-in-command of Churchill’s former regiment, the 4th Queen’s Own Hussars, where he learns to drive a tank and takes part in the liberation of Italy.

The Churchill connection appears to be a long thread in the family: Charles Barne’s great-grandfather encountered the great man in the trenches during World War I.

But neither of the older Barnes appears to have been a fan — initially, at least.

The diarist writes of his disapproval when Churchill becomes prime minister on 10 May 1940: “Churchill is now PM. A gentleman has gone and a clever cad has replaced him. No doubt he will be hailed with great joy in most quarters because he has not forgotten to advertise himself. I only hope I live to eat this page!”

As Churchill galvanises the nation and his stock rises, Barne’s tone changes to a more reverential one.

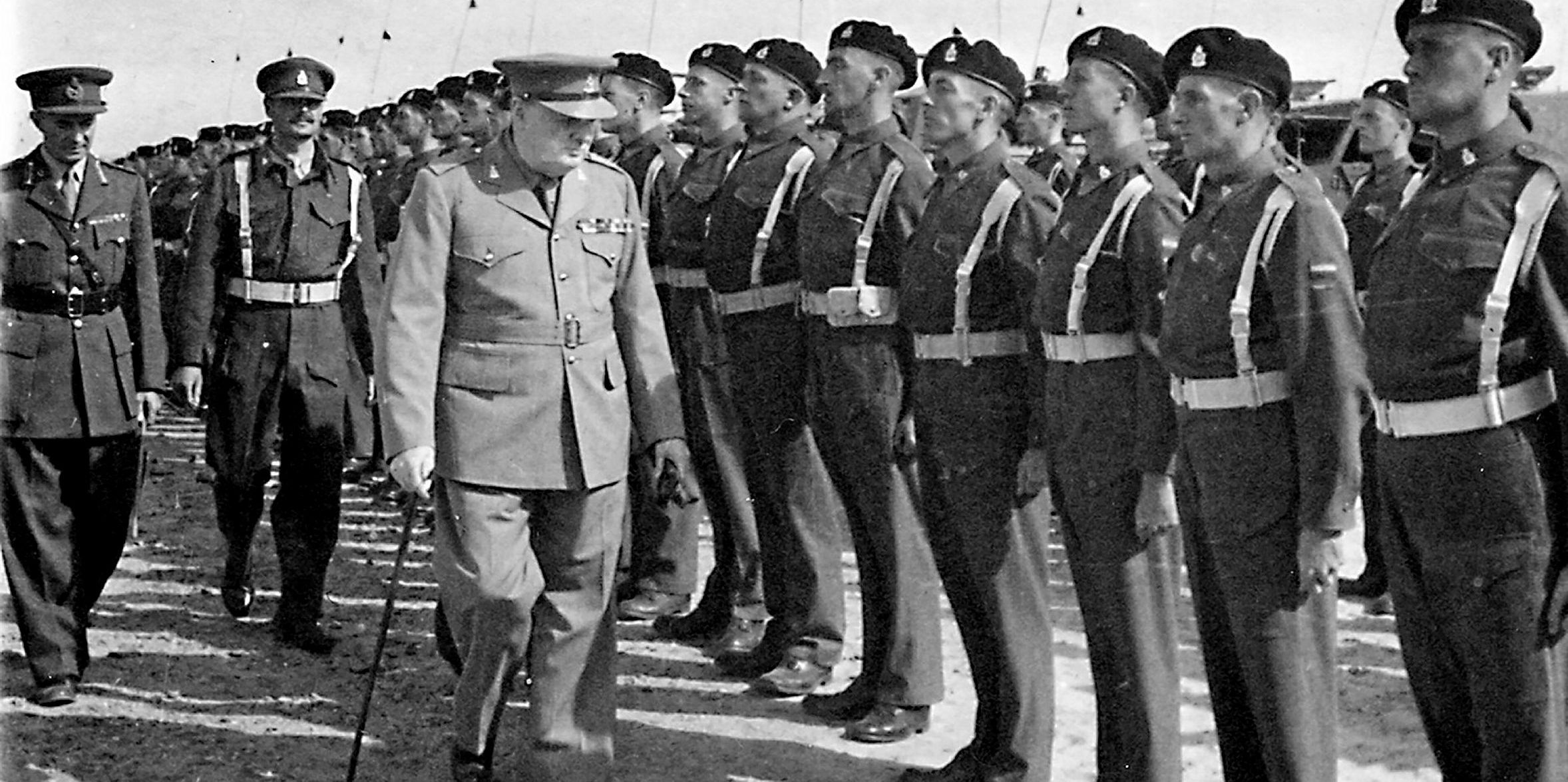

Churchill was in the 4th Hussars for four years and later became honorary colonel of the regiment, keeping in touch with it and visiting several times during the war, when Barne was by then its commander.

During the 69-year-old PM’s visit to the Hussars in Egypt in December 1943, Barne records: “Churchill has got an amazingly agile brain and, despite his bulk, excesses and age, still seems a young man. He has fine, silky fair hair and an enormous back but with no waist.”

An incident in which Churchill loses his glass of sherry causes a stir but otherwise the honoured guest enjoys a hastily organised parade of his troops, all recorded on newsreel footage.

It is, perhaps, Anthony Barne’s post-war encounter with Churchill that makes for some of the most fascinating reading.

Voted out of office in July 1945 as Britain tries to rebuild, Churchill goes off to Lake Como in northern Italy and Barne is invited to visit.

It is an awkward encounter at first, but the two go on to spend some close time together, as Barne’s description of a swimming expedition with Churchill shows.

“We had a speed boat and a police launch so could evade the Italians. Once he wanted a swim and nearly swamped our light craft when getting overboard. I could then not get him back onboard though we both struggled hard so I towed him in to the shallows and signalled to Sarah [Churchill’s daughter]. She waded out to help him. He looked like a great pink baby emerging from the water.”

Lord Moran, Churchill’s personal physician, recalled Barne’s arrival at Villa Rosa in his 1966 book The Struggle for Survival. “I told him Winston was out. We talked in a desultory way for some time. He was a typical cavalry soldier of the old kind, very conscious of the fabric of English society and of the anatomy of the horse …” he wrote.

Churchill was a little kinder. “A most agreeable man” is how he later described Anthony Barne in letters researched by his grandson, about a piece of history brought vividly to life by his grandfather’s diaries as it slides from living memory.

Thirsty work | ‘A lot of late nights in Cairo’

Military and cavalry officers run in Charles Barne’s family. In fact, he is the exception, having never been in the ranks and being unable to ride.

He lived among, and has inherited, some “amazing military memorabilia” from his family, including drums, hats, swords, a pig-sticking lance and part of the fuselage of an Italian bomber, complete with bullet holes.

He remembers his grandfather as “very kindly, patient and supportive”, with “a twinkle in his eye” and “a mischievous irreverent side”, but his stiff military air earned him the nickname The Colonel in his village.

A move out of London three years ago galvanised Charles into reading his grandfather’s diaries, later into putting them into something more meaningful. “I wanted the full narrative sweep of not just his journey but also the progression of the war,” he says.

It is not lost on him that he and Anthony were at similar ages when they started the writing process — in their 30s, married and with young children.

“It gave him more context as a man, rather than a grandfather,” Charles says of what he has read and written. “He was an elderly, kind man when I knew him. Here [in the diaries] he is very sprightly, quite gregarious and ‘thirsty’. There’s a lot of late nights in Cairo.”

Charles edited the diaries and admits this was the most challenging process, particularly after “a bad day when a ship has failed on subjects”.

He wrote a prologue, the first chapter describing his grandfather’s early years, an opening scene-setter for each chapter and an epilogue that references Anthony Barne’s “infuriatingly brief account of lunch alone with the Churchills”. Lykiardopulo’s in-house lawyer, Philip Young, helped proof-read his work.

A broker at heart, it was with some shock that Charles learnt that 20% of the book’s royalties go to his agent, something a shipbroker could only dream of.

Charles, who studied economics and French at university, counts this as his first real published work, despite self-publishing children’s books for his two daughters. He hopes they will read this one as teenagers. “I’ve loved it. It has been totally absorbing. I already miss it.” It may not be his last book. The two subjects he keeps returning to are World War II and Antarctica, which he is keen to visit.

He reveals another family “secret”: Anthony Barne’s uncle, Michael Barne, went to Antarctica with Captain Scott on his first 1901-04 expedition there on his ship Discovery. Barne Inlet on the Ross Ice Shelf is named after him. Michael left a wealth of themed memorabilia, including a stuffed penguin — and also wrote some diaries. “That might be something I’d look at,” Charles says coyly.

Churchill’s Colonel will be published by Pen & Sword in the week of 7 October