RightShip has again sounded the alarm over crew abandonment as case numbers in 2022 reached a 20-year high.

The environmental, social and governance (ESG)-focused digital maritime platform said the Covid-19 pandemic and conflict-induced abandonment are the leading drivers of the uptick.

RightShip, as part of an urgent review to highlight “this concerning trend and spur the industry to action”, said its research found that 9,925 seafarers were abandoned on their ships over the past two decades, with their unpaid wages adding up to $40m.

Last year alone, 1,682 seafarers on 103 ships were “cast adrift”, with cases recorded in countries “across all continents”.

RightShip’s research indicates that cases of reported abandonment have been on the rise for five consecutive years, following other notable peaks forced by the 2008 financial crash and the 2017 Maritime Labour Convention.

The International Maritime Organisation’s definition of abandonment is when a shipowner is unable to cover the cost of a seafarer’s repatriation and fails to pay wages for at least two months, has left seafarers without maintenance and support, or otherwise severs ties with the crew.

“In cases of sudden abandonment, these people are left to suffer without food, water, supplies, medicine and the ability to reach shore to contact anyone,” said RightShip.

“Living under these conditions can have devastating consequences, including loss of life through neglect or suicide.”

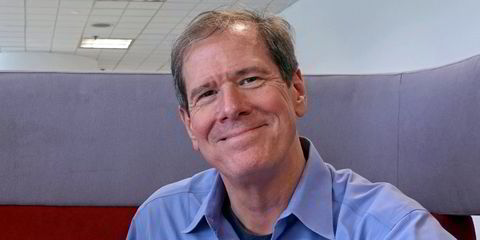

RightShip chief executive Steen Lund said: “When abandoned on vessels, seafarers are left alone to fend for themselves while corporations avoid their responsibilities. When those who destroy the lives of seafarers also employ them, it is, in all senses, deeply troubling”.

However, he said that as regulators and RightShip begin to clamp down on due diligence at all points in the supply chain, “there will be catastrophic financial implications for those who partner with disreputable ship managers”.

According to Lund, the rise in ESG compliance regulations means charterers, bankers and financiers are increasingly being asked to perform due diligence when it comes to selecting their partners, with open abandonment cases reflecting poorly on shipowners and managers.

“We already identify vessels guilty of abandonment linked to a company in the RightShip Platform,” he said.

“We cannot and will not recommend them to our customers for voyages and we mark them unacceptable during the vetting process.

“Operators who have little regard for the welfare and human rights of their crew must not be allowed to continue to operate.”

Lund said more than 1,000 ship management companies have “not declared their hand” by refraining from completing RightShip’s crew welfare self-assessment.

The assessment, according to RightShip, encourages organisations to engage with and improve crew welfare and — in conjunction with crew abandonment data in the RightShip Platform — allows charterers to select vessel owners and managers that have made public commitments to high welfare standards.

“When seafarer abandonment still happens, it is largely down to the ruthlessness of capitalism. Wanting to eliminate the issue means putting in place your best management practices to stop it,” Lund concluded.