Greek maritime tradition goes back thousands of years.

Fraud is one of the more unsavoury parts of that otherwise glorious heritage — and it began sooner than one might think.

In 360 BC, two shipowners from Syracuse, Italy — Zenothemes and Egistratus — received an advance payment for a grain load to be delivered.

However, when the vessel that was meant to carry the cargo sailed from the Sicilian city, its holds were empty.

Three days out at sea, Egistratus started damaging a beam in the hope of scuttling the ship. Passengers caught wind of it and confronted him. In his panic, Egistratus jumped overboard and drowned.

Fraudsters have been much more successful in the centuries that followed.

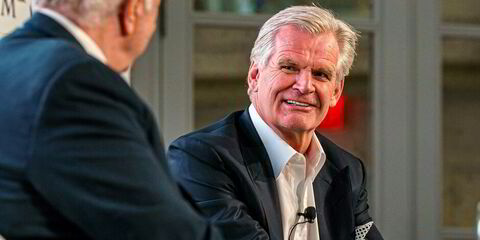

George Trantalides, a 74-year-old attorney who still practises maritime law in Piraeus, set out to document and classify dozens of cases that have made headlines since the 1950s, in his home country and abroad.

“I’ve spent 30 years collecting material for this work,” he told TradeWinds, recounting how he cut press clippings by hand or unearthed files from state archives and court libraries.

“I’ve saved all these old documents with the wish that the maritime fraud that has sullied the name of Greek shipping isn’t repeated.”

A teacher’s son, born in Rethymnon in Crete, Trantalides has been a pioneer in the field.

Appearing in court or sending thousands of letters to the media over the course of his career, he has been a stalwart defender of victims’ families in pursuing callous or negligent shipowners.

He also claims to be the first Greek lawyer to turn his guns on classification societies.

In the foreword to his work published in Greek earlier this year, Trantalides explained that he wrote the book as a clarion call to increase awareness and make sure maritime fraud is tackled more effectively.

“If the book helps uncover even one criminal case, it will have fulfilled its purpose,” he wrote.

Trantalides directs much of his ire towards politicians.

In a sharp-tongued afterword to his 386-page book, he describes many of Greece’s shipping ministers as hapless amateurs, parachuted into their positions and then reshuffled before having had the time to become even remotely familiar with the subject.

Justice ministers do not escape criticism. According to the lawyer, ill-guided Greek legal reform turned felonies into misdemeanours, practically leading to impunity for criminals.

Victims of maritime fraud also carry responsibility, Trantalides argues. Collecting the insurance money is often all they care about and they fail to provide evidence or testimony that would help prosecutors get to the bottom of cases.

In a brief analysis that precedes the presentation of individual cases, Trantalides breaks down maritime fraud into broad categories.

In the first, loaded ships are diverted from their official destination. The cargo is then clandestinely sold and the ship is scuttled or burned by arsonists.

In a “ghost cargo” variant of this practice, charterers are stonewalled with the excuse that the ship carrying their cargo is undergoing repairs.

In reality, the cargo is stolen — transferred to another vessel or sold on land. The chartered ship is then declared a total loss, camouflaged, repainted, sold or simply scuttled.

Then there is the classical insurance fraud, in which ships, usually more than 15 years old, are insured at twice their real value and then deliberately sunk. Fraudsters often cash in at the insurance of both the hull and the cargo.

Silver linings

However, things are improving and the scope for fraudsters to do their dirty work has narrowed, Trantalides said.

For one thing, litigation has become more aggressive.

“Shipwrecks have become much less common because there’s fear of lawsuits from the drowned persons’ relatives,” he told TradeWinds.

Advances in technology have also helped. Court-appointed experts no longer need to be physically on a ship to draw meaningful conclusions.

“A good naval architect can now detect the causes of a shipwreck just by looking at a ship’s file,” he said.

In another positive development, Greece has finally been making moves to overhaul its outdated maritime law.

The private maritime law code, unchanged since 1958, has now been updated to reflect modern standards and will soon be enacted into law, Greek shipping minister Yiannis Plakiotakis said in May.

Times are getting harder for Egistratus’ successors.