Shipping regulators admit that serious safety questions need to be answered in the 22 months before the global 0.5% limit on the sulphur content of fuel comes into force.

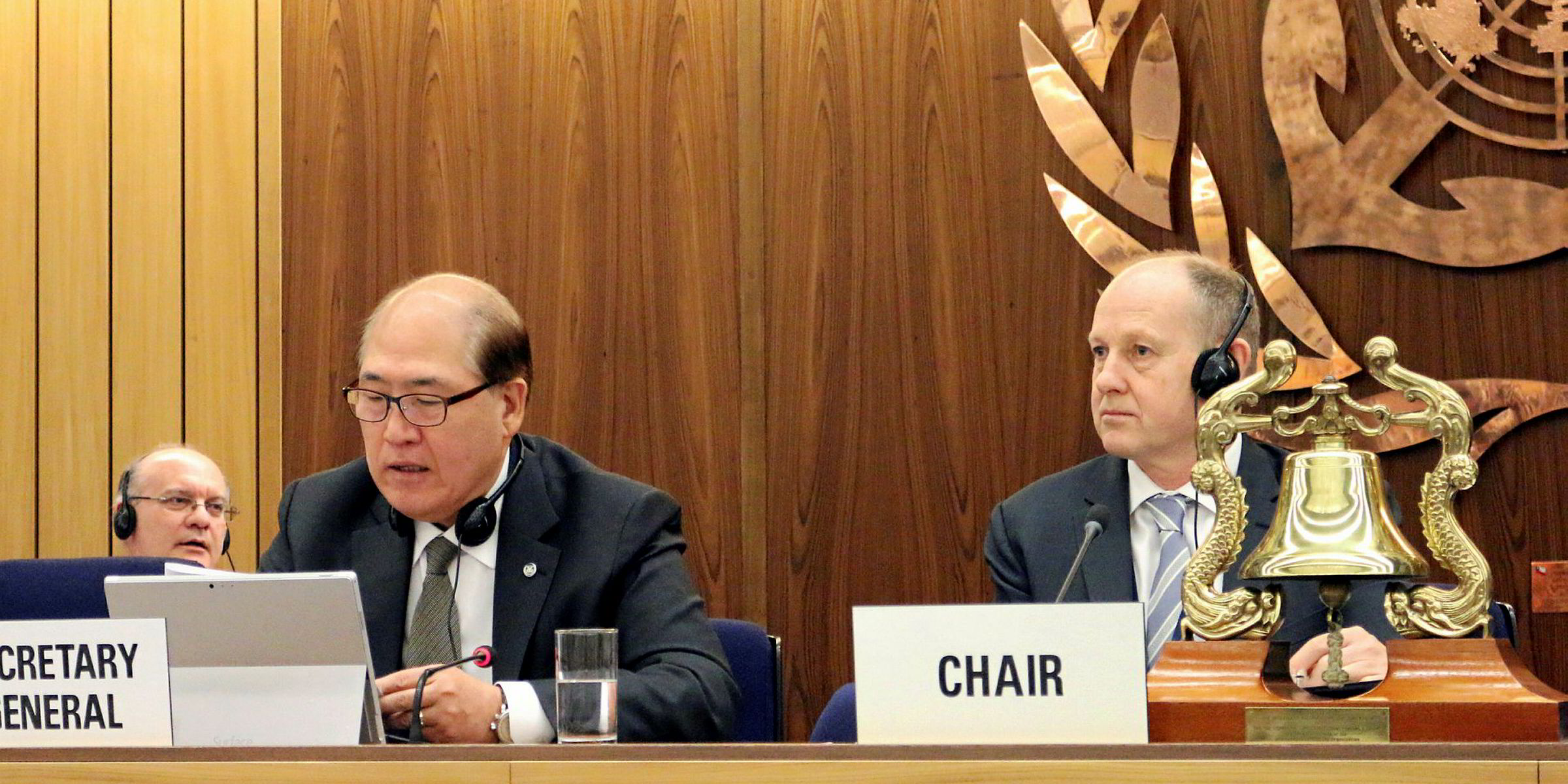

When IMO delegates sat down in London this month to discuss the 2020 introduction of the new limit, talks focused on port state and flag state policing and enforcement.

The thrust of the discussion centred around deterring non-compliance and creating a level playing field for commercial competition.

The headline decision was to approve a shipowner-backed proposal that would prohibit the carriage of non-compliant fuel unless a scrubber or alternative abatement equipment had been installed. The idea was that no ship should have the opportunity to burn heavy fuel oil (HFO) even if it was using low-sulphur fuel at the time of inspection.

Yet members of the Pollution Prevention and Response (PPR) subcommittee meeting recognised that despite the prominence of commercial issues, the industry faces serious safety issues relating to the upcoming regulations.

One argument tabled was that safety was not such a concern because owners and managers already had plenty of technical experience in low-sulphur fuel and fuel switching from trading in sulphur emission control areas (SECAs) in northern Europe and the US.

But what about the thousands of vessels operating outside those regions that must now comply with the upcoming Marpol Annex VI global sulphur regulation?

One big issue touched on by the PPR meeting was how ship machinery would react to operating with much lower viscosity fuels such as marine gas oil (MGO).

Fractures and gaps in pipes could emerge that were not apparent when using much thicker HFOs, and leakages could pose a threat of breakdown or fire.

The IMO has identified potential danger areas, such as the fuel pump puncture valve, auxiliary boiler, pump seals, supply and circulation pumps and fuel oil filters.

Other machinery failures that could result from switching to MGO include a stuck fuel pump plunger, and barrel and nozzle damage in the fuel injection valve. Concern was also raised about the safety of boilers in steam-turbine ships operating with MGO.

The US Coast Guard recorded a significant number of breakdowns following the introduction of the North American SECA, and engine failures were also reported in northern Europe.

One IMO delegate said: “The industry needs to see technical guidelines issued on the potential onboard issues that could result from switching over to low-sulphur fuel, or we could see what happened in North America and Europe repeated on a global scale.”

The IMO also recognised that there is a safety issue with the low-sulphur fuel itself.

While MGO is expected to be the initial option for most shipowners to comply with the new regulations, blended fuel oils — made up of as much as 80% MGO and the rest high-sulphur HFO — are eventually expected to become more widely used.

The IMO acknowledged that the quality and safety of this new generation of ultra-low sulphur fuel oils need to be examined.

It agreed to develop guidelines for shipowners that choose blended fuels to comply with the change-over. One problem is that these blended fuels are unlikely to be made up and tested until just before January 2020, because there will be no demand until then.

And there could be problems not only with quality but also with the compatibility of fuels going into the blend, and whether it will blend with residual fuel in the tanks.

The safety concerns are being taken forward to the IMO's Marine Environment Protection Committee meeting in April and the IMO hopes to complete its safety guidelines by next year's PPR meeting.