Pressure to slash emissions has led Norwegian researchers to re-examine the feasibility of nuclear-powered merchant ships.

High building and decommissioning costs, plus issues of political and social acceptance, remain major obstacles, according to Halvor Schoyen, associate professor of maritime logistics at the University College of Southeast Norway — but there could be niche roles for high-speed vessels carrying high-value cargoes.

Schoyen and co-author Kenn Steger-Jensen of Aalborg University in Denmark point to the possibility of a slow-steaming 20,000-teu Triple-E containership being replaced by a 35-knot, 270-megawatt nuclear boxship with a capacity of 9,200 teu.

But the limitations are still huge, as they point out in a research article, "Nuclear propulsion in ocean merchant shipping: The role of historical experiments to gain insight into possible future applications", published in the Journal of Cleaner Production.

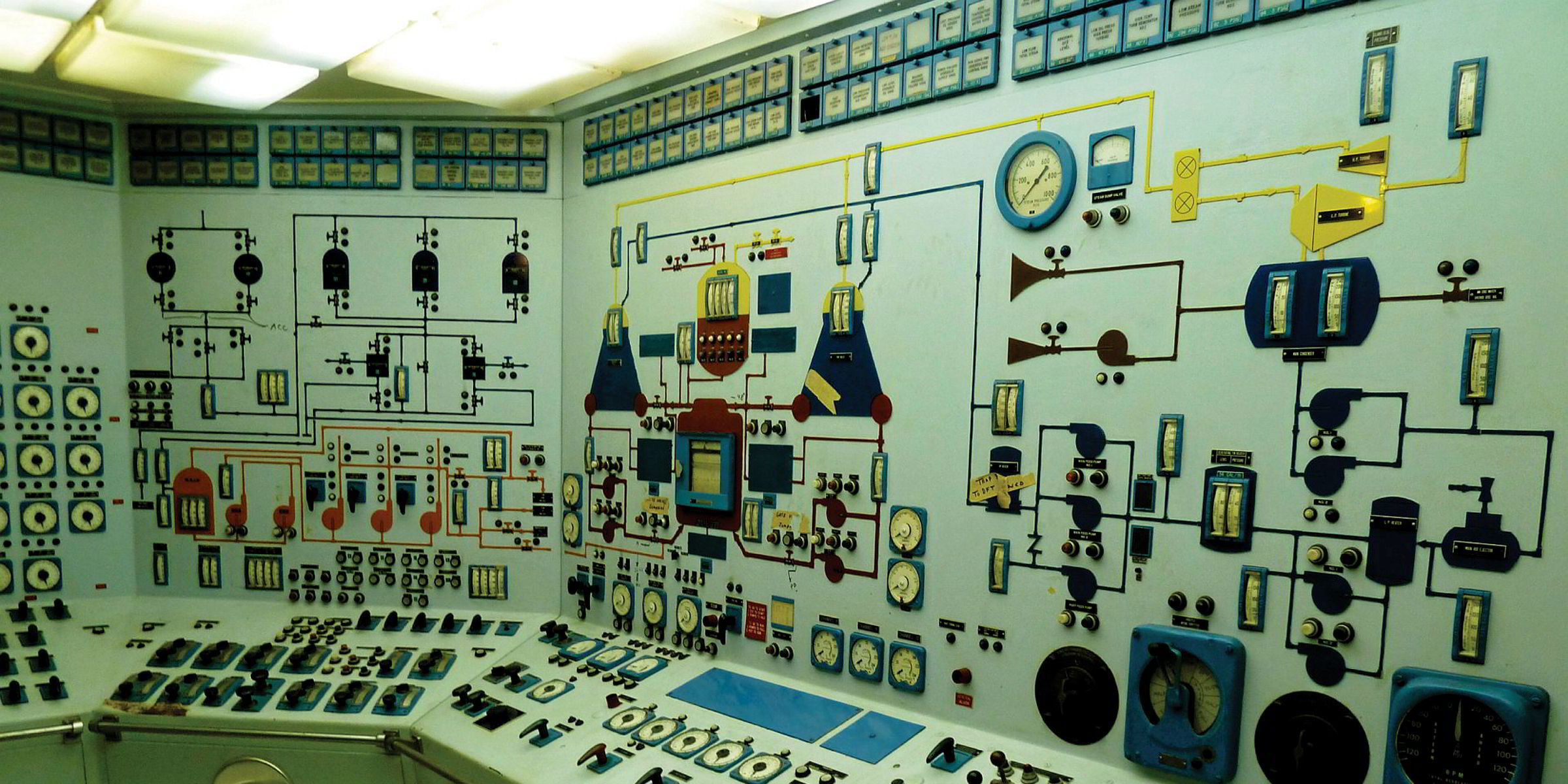

Four experimental ships were built in the 1960s to 1980s, when it was estimated the upfront cost for a commercial ship’s nuclear propulsion plant was seven times that of an oil-fired engine of equivalent horsepower — and this would double or triple the overall price.

A cost increase of two to 2.5 times was estimated by class society DNV in 2010, which added that price calculations remained “highly uncertain”.

Maintenance, repair, manning, insurance and security costs are also likely to be higher for a nuclear vessel, the report says, but fuel costs could be lower.

- The Savannah travelled 450,000 nautical miles in 10 years on nuclear power, with one refuelling, before ending service. It is currently in Baltimore, where it is set to be converted into a museum.

- The Otto Hahn sailed 650,000 miles in nine years on nuclear power, using two fuel cores. Each refuelling took about 10 weeks. Its reactor was decommissioned in 1979 and the ship scrapped in 2009.

- The Mutsu’s total project cost was put at $1.2bn after the reactor was decommissioned in 1995. Converted into an ocean-observation ship with a diesel engine, it is still in service as the Mirai.

- The Sevmorput and its reactor are reported to have operated for more than 20 years without major incidents, although the ship was laid up for a decade in the wake of the 1986 Chernobyl disaster.

However, uncertainty about refuelling intervals and time taken out of service, plus the high cost of decommissioning, are problematic for any owner other than a national government.

The first three maritime nuclear vessels — the US Maritime Administration’s passenger-freight ship Savannah (built 1961), West German state company GKSS' Otto Hahn (built 1964) and the Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute’s Mutsu (built 1970) — were unable to carry containers.

“These three experimental nuclear ships failed to prosper commercially with respect to freight service, due to high ship-operating expenses and unsuitable mission selection linked to routes and cargoes,” the report says.

The fourth vessel, the USSR’s Sevmorput (built 1986), was constructed for commercial operations in remote Arctic waters.

All four encountered political opposition, with the Savannah barred from ports in Australia, New Zealand and Japan, the Otto Hahn denied passage through the Suez Canal and Dutch ports, and the Mutsu even excluded from its home port after its reactor started to leak fast neutrons on its maiden voyage in 1974.

But the issue of emissions opens up possibilities.

About 886 containerships above 5,000 teu, on average, are slow-steaming at 17.2 knots, emitting about 81.7 million tonnes of CO2 per year, or 40% of the global annual boxship output. The report argues: “Nuclear-powered high speeds and smaller ship size could possibly serve shippers’ demands in a market niche for fast-moving, high-value cargo ocean transport service.”