The Indian shipbreaking centre of Alang has come a long way since the dark days of two decades ago, when clandestine photographs taken by non-governmental organisations and environmental watchdogs showed ships being hacked apart with little regard for the environment or the safety of its workers.

Similar scenes were recorded at the shipbreaking beaches of Gadani in Pakistan and Chittagong in Bangladesh.

Owners claim they want to be responsible when it comes to recycling their ships, but they are not willing to negotiate on price

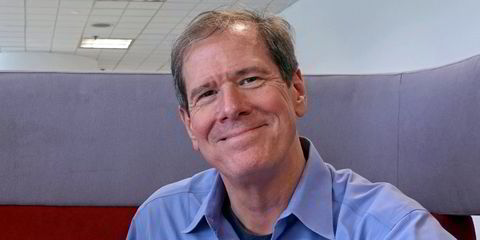

Raza Meghani, director of Rai Metal Works

The negative publicity generated by these photographs worldwide, especially in Europe, played a large role in clean-up efforts in South Asian.

Tighter control

Support from classification societies and foreign government bodies, together with increased regulatory control from New Delhi and the Government of Gujarat also played a role, as did the younger generation of better-educated and environmentally aware shipbreakers moving up the ranks of the family business.

Today, after years of change, shiprecyclers in South Asia are working to overcome even tighter restrictions. Their facilities must comply with the European Union's Ship Recycling Regulation (SRR) and prepare to meet the challenges of the next convention as it nears ratification — the Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships

While facilities that have invested in improvements are expressing confidence, players in the sector argue that shipowners need to recognise that greener shiprecycling means more expensive recycling.

Satinder Pal Singh, joint secretary of India’s Ministry of Shipping, currently estimates that 77 of the 130 active shipbreaking plots at Alang are certified to the Hong Kong Convention.

Pakistan and Bangladesh have a lot of work ahead before they can achieve the same standards now found at Alang. Government officials from both countries say they are working hard to catch up. Bangladeshi officials estimate it could take four to five years before the country could ratify the Hong Kong Convention.

The improvements at Alang are already being felt. AP Moller-Maersk and China Navigation Co, both of which previously shunned South Asia, are once again sending their ships there for recycling. Even the New Zealand government is recycling its ships in the region.

Two-tier market

But compliant-yard owners complain they seldom receive a price premium to cover the cost of dismantling tonnage to the Hong Kong Convention standards. Some argue this has created a two-tier market and is keeping other shipyrecyclers from upgrading their facilities.

Raza Meghani, director of Rai Metal Works, an Alang-based shiprecycling facility that is certified to the Hong Kong Convention, says the problem is that his company has invested a lot of money but it's “not getting a consistency of ships”.

“Owners claim they want to be responsible when it comes to recycling their ships, but they are not willing to negotiate on price,” he says.

Meghani, who is in his mid-twenties and recently completed his tertiary education in Canada, represents the new generation of Indian shiprecyclers.

He argues that once shipowners, who want their ships to be recycled in a green manner, realise they are not going to get the same money as they would from a non-green yard, and are prepared to take the hit, will the overall level of shiprecycling in South Asia improve.

“I care about the environment and nature, and the welfare of our workers. I want to follow HKC [Hong Kong Convention] and EU rules. This means my costs go up, but the selling price for my base product — steel — remains the same.”

“Nobody wants to be in business to make a loss. What is happening is that many breakers are not willing to put in more money because they cannot see the financial returns.”

Guarav Mehta, director of Alang-based Priya Blue Industries, says that while a growing number of owners are willing to sell for less to get green recycling, there is still not enough supply to support Alang’s Hong Kong Convention-compliant yards.

“The capacity is certainly there. The problem is there are not enough ships,” he explains.

Long-term confidence

Managers at some Hong Kong Convention-certified yards in South Asia remain confident their investments will pay off in the long run.

With India expected to ratify the convention later this year, and Bangladesh promising to do so in four to five years, they expect that non-compliant yards will either up their game or be forced out of business.

Mohammed Zahirul Islam, managing director at PHP Ship Breaking and Recycling, Bangladesh’s first Hong Kong Convention-certified yard, notes that at least another seven yards in Chittagong have engaged with international consultants to begin the upgrades.

Bold ambitions

“Our government’s Ship Recycling Act of 2018 stipulates that all facilities need to be HKC [Hong Kong Convention] compliant by 2018. We can already see good movement towards this in Bangladesh,” Zahirul says.

Similarly, Sanjiv Agarwal, director of Alang’s JRD Industries, believes that although the path to gaining such approval is challenging, it is worth it for the entire shiprecycling industry.

“It gives an indication of the changes that are coming, and where things will go in the future,” says Agarwal, whose facility is one of three yards that are in the process of applying for EU approval.