The car carrier fleet this year is expected to see the highest number of newbuilding deliveries since 2012.

Fleet growth comes as volumes of overseas vehicle shipments into the largest market, North America, return to pre-recession levels.

But shipowners are tempering expectations for further growth as North American car buying appears to be hitting a peak. In addition, US president Donald Trump’s new administration adds new risk to trade.

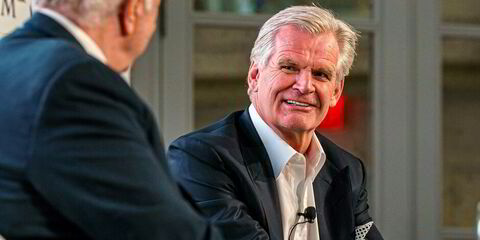

Ari Marjamaa, head of market intelligence at Wallenius Wilhelmsen Logistics, says the market has a lot of capacity to absorb in 2017. But scrapping and delays in newbuilding orders should help overall fleet balances in coming years.

This year “is not going to do us any favours in terms of the orderbook”, says Marjamaa. “But it does seem to better going forward.”

Clarksons’ data shows there are 35 newbuildings for delivery this year, one short of 2012’s total. In terms of car equivalent units, those newbuildings represent capacity growth of just over 6%.

Italy’s Grimaldi Group accounts for the largest number of newbuildings ordered with seven set for delivery this year.

South Korea’s Hyundai Glovis and Sweden’s Wallenius Lines are each expected to take in four newbuildings.

The new vessels coincide with six years of growth for overseas auto imports into the US. In 2015, imports hit 3.97 million vehicles, surpassing the previous high of 3.61 million in 2008, according to the US Department of Commerce.

But that growth is tapering. Unit volumes into the US for the first nine months of last year were 2.93 million, equal to the number of units delivered over the same period in 2015.

“We don’t expect [US imports] to grow much further,” Marjamaa said. “The potency of the market is reduced compared to what it was four or five years ago.”

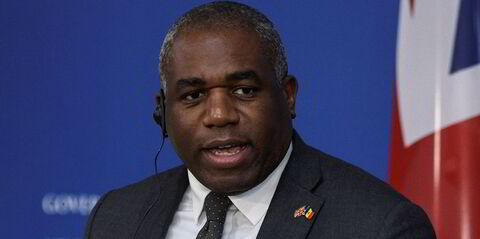

Niklas Carlen, analyst at consultancy Maritime Strategies International, says seaborne volumes into the US market are expected to slow due to new auto plants in the US and Mexico that ship overland. The push to boost US manufacturing and the potential for tariffs on imported goods threatens overseas imports more.

“There’s going to be a risk if you see more punitive measures taken against imports,” Carlen said.

Marjamaa, who says Wallenius Wilhelmsen vessels have about 20% share of transatlantic voyages to North America, says current trade talks are “making people jittery”. But he sees more posturing than real threats to trade.

“I don’t think anyone really wants to undercut trade, because it’s a two-way game. You wouldn’t expect to have a one-way trade war,” he said.

More US manufacturing could mean more exports, Marjamaa says. He expects US exports to grow from one million units to about 1.3 million units over the next five years. In addition, Mexico’s auto manufacturing capacity could see more overseas exports should the US market close.

Those offsets to flattening US imports, and recovery in other markets, should drive long-term global demand growth for deep-sea transport of cars of about 2%, which would be ideal fleet growth, Marjamaa says.

Hitting that mark will require more scrapping, particularly of smaller vessels, Carlen says. Last year was the third highest ever for scrapping, with just over 20 ships, representing 4% of capacity.

Marjamaa adds that scrapping should see similar levels this year. Along with delayed or cancelled newbuildings, supply and demand balances should right themselves, he says.

“There is quite a bit of slippage in fleet delivery,” Marjamaa said. “It seems that owners are keen to postpone deliveries.”